Common sense

[citation needed] Relevant terms from other languages used in such discussions include the aforementioned Latin, itself translating Ancient Greek κοινὴ αἴσθησις (koinḕ aísthēsis), and French bon sens.

[6] It was at the beginning of the 18th century that this old philosophical term first acquired its modern English meaning: "Those plain, self-evident truths or conventional wisdom that one needed no sophistication to grasp and no proof to accept precisely because they accorded so well with the basic (common sense) intellectual capacities and experiences of the whole social body.

[3] Today, the concept of common sense, and how it should best be used, remains linked to many of the most perennial topics in epistemology and ethics, with special focus often directed at the philosophy of the modern social sciences.

Heller-Roazen (2008) writes that "In different ways the philosophers of medieval Latin and Arabic tradition, from Al-Farabi to Avicenna, Averroës, Albert, and Thomas, found in the De Anima and the Parva Naturalia the scattered elements of a coherent doctrine of the "central" faculty of the sensuous soul.

Aristotle never fully spells out the relationship between the common sense and the imaginative faculty (φᾰντᾰσῐ́ᾱ, phantasíā), although the two clearly work together in animals, and not only humans, for example in order to enable a perception of time.

[17][19] Despite hints by Aristotle himself that they were united, early commentators such as Alexander of Aphrodisias and Al-Farabi felt they were distinct, but later, Avicenna emphasized the link, influencing future authors including Christian philosophers.

[24] Plato, on the other hand was apparently willing to allow that animals could have some level of thought, meaning that he did not have to explain their sometimes complex behavior with a strict division between high-level perception processing and the human-like thinking such as being able to form opinions.

[25] Gregorić additionally argues that Aristotle can be interpreted as using the verbs phroneîn and noeîn to distinguish two types of thinking or awareness, the first being found in animals and the second unique to humans and involving reason.

In his Rhetoric for example Aristotle mentions "koinōn [...] tàs písteis" or "common beliefs", saying that "our proofs and arguments must rest on generally accepted principles, [...] when speaking of converse with the multitude".

[33] In a similar passage in his own work on rhetoric, De Oratore, Cicero wrote that "in oratory the very cardinal sin is to depart from the language of everyday life and the usage approved by the sense of the community."

As with other meanings of common sense, for the Romans of the classical era "it designates a sensibility shared by all, from which one may deduce a number of fundamental judgments, that need not, or cannot, be questioned by rational reflection".

[38] Apart from Cicero, Quintilian, Lucretius, Seneca, Horace and some of the most influential Roman authors influenced by Aristotle's rhetoric and philosophy used the Latin term "sensus communis" in a range of such ways.

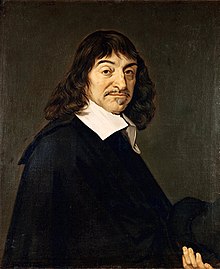

Gilson noted that Descartes actually gave bon sens two related meanings, first the basic and widely shared ability to judge true and false, which he also calls raison (lit.

In France, the Netherlands, Belgium, Spain and Italy, it was in its initial florescence associated with the administration of Catholic empires of the competing Bourbon, and Habsburg dynasties, both seeking to centralize their power in a modern way, responding to Machiavellianism and Protestantism as part of the Counter-Reformation.

On the other hand, like the Scholastics before him, while being cautious of common sense, Descartes was instead seen to rely too much on undemonstrable metaphysical assumptions in order to justify his method, especially in its separation of mind and body (with the sensus communis linking them).

Cartesians such as Henricus Regius, Geraud de Cordemoy, and Nicolas Malebranche realized that Descartes's logic could give no evidence of the "external world" at all, meaning it had to be taken on faith.

Do they not feel in themselves, that what pleases at one time, displeases at another, by the change of inclination; and that it is not in their power, by their utmost efforts, to recall that taste or appetite, which formerly bestowed charms on what now appears indifferent or disagreeable?

With this in mind, Shaftesbury and Giambattista Vico presented new arguments for the importance of the Roman understanding of common sense, in what is now often referred to, after Hans-Georg Gadamer, as a humanist interpretation of the term.

Another connected epistemological concern was that by considering common good sense as inherently inferior to Cartesian conclusions developed from simple assumptions, an important type of wisdom was being arrogantly ignored.

He drew upon authors such as Seneca, Juvenal, Horace and Marcus Aurelius, for whom, he saw, common sense was not just a reference to widely held vulgar opinions, but something cultivated among educated people living in better communities.

According to Gadamer, at least in French and British philosophy a moral element in appeals to common sense (or bon sens), such as found in Reid, remains normal to this day.

Gadamer notes one less-known exception—the Württemberg pietism, inspired by the 18th century Swabian churchman, M. Friedrich Christoph Oetinger, who appealed to Enlightenment figures in his critique of the Cartesian rationalism of Leibniz and Wolff, who were the most important German philosophers before Kant.

[66] Vico, who taught classical rhetoric in Naples (where Shaftesbury died) under a Cartesian-influenced Spanish government, was not widely read until the 20th century, but his writings on common sense have been an important influence upon Hans-Georg Gadamer, Benedetto Croce and Antonio Gramsci.

[67] Vico's initial use of the term, which was of much inspiration to Gadamer for example, appears in his On the Study Methods of our Time, which was partly a defense of his own profession, given the reformist pressure upon both his University and the legal system in Naples.

The imagination or fantasy, which under traditional Aristotelianism was often equated with the koinḕ aísthēsis, is built up under this training, becoming the "fund" (to use Schaeffer's term) accepting not only memories of things seen by an individual, but also metaphors and images known in the community, including the ones out of which language itself is made.

[78] Kant himself did not see himself as a relativist, and was aiming to give knowledge a more solid basis, but as Richard J. Bernstein remarks, reviewing this same critique of Gadamer: Once we begin to question whether there is a common faculty of taste (a sensus communis), we are easily led down the path to relativism.

[82] In a parallel development, Antonio Gramsci, Benedetto Croce, and later Hans-Georg Gadamer took inspiration from Vico's understanding of common sense as a kind of wisdom of nations, going beyond Cartesian method.

It has been suggested that Gadamer's most well-known work, Truth and Method, can be read as an "extended meditation on the implications of Vico's defense of the rhetorical tradition in response to the nascent methodologism that ultimately dominated academic enquiry".

As Gadamer wrote in the "Afterword" of Truth and Method, "I find it frighteningly unreal when people like Habermas ascribe to rhetoric a compulsory quality that one must reject in favor of unconstrained, rational dialogue".

[85][86] A recent commentator on Vico, John D. Schaeffer has argued that Gadamer's approach to sensus communis exposed itself to the criticism of Habermas because it "privatized" it, removing it from a changing and oral community, following the Greek philosophers in rejecting true communal rhetoric, in favour of forcing the concept within a Socratic dialectic aimed at truth.