Time signature

A mid-score time signature, usually immediately following a barline, indicates a change of meter.

Conversely, at slow tempos, the beat might even be a smaller note value than the one enumerated by the time signature.

Other time signature rewritings are possible: most commonly a simple time-signature with triplets translates into a compound meter.

Particular time signatures are traditionally associated with different music styles—it would seem strange to notate a conventional rock song in 48 or 42, rather than 44.

Early anomalous examples appeared in Spain between 1516 and 1520,[8] plus a small section in Handel's opera Orlando (1733).

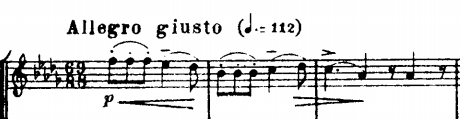

The waltz-like second movement of Tchaikovsky's Pathétique Symphony (shown below), often described as a "limping waltz",[9] is a notable example of 54 time in orchestral music.

They played other compositions in 114 ("Eleven Four"), 74 ("Unsquare Dance"), and 98 ("Blue Rondo à la Turk"), expressed as 2+2+2+38.

"Blue Rondo à la Turk" is an example of a signature that, despite appearing merely compound triple, is actually more complex.

Charles Ives's Concord Sonata has measure bars for select passages, but the majority of the work is unbarred.

Sometimes one is provided (usually 44) so that the performer finds the piece easier to read, and simply has "free time" written as a direction.

The stress pattern is usually counted as This kind of time signature is commonly used to notate folk and non-Western types of music.

The first movement of Maurice Ravel's Piano Trio in A Minor is written in 88, in which the beats are likewise subdivided into 3+2+3 to reflect Basque dance rhythms.

Romanian musicologist Constantin Brăiloiu had a special interest in compound time signatures, developed while studying the traditional music of certain regions in his country.

While investigating the origins of such unusual meters, he learned that they were even more characteristic of the traditional music of neighboring peoples (e.g., the Bulgarians).

This type of meter is called aksak (the Turkish word for "limping"), impeded, jolting, or shaking, and is described as an irregular bichronic rhythm.

[clarification needed] The Macedonian 3+2+2+3+2 meter is even more complicated, with heavier time bends, and use of quadruples on the threes.

[citation needed] Brăiloiu borrowed a term from Turkish medieval music theory: aksak.

However, aksak rhythm figures occur not only in a few European countries, but on all continents, featuring various combinations of the two and three sequences.

According to Brian Ferneyhough, metric modulation is "a somewhat distant analogy" to his own use of "irrational time signatures" as a sort of rhythmic dissonance.

Sometimes, successive metric relationships between bars are so convoluted that the pure use of irrational signatures would quickly render the notation extremely hard to penetrate.

Good examples, written entirely in conventional signatures with the aid of between-bar specified metric relationships, occur a number of times in John Adams' opera Nixon in China (1987), where the sole use of irrational signatures would quickly produce massive numerators and denominators.

Henry Cowell's piano piece Fabric (1920) employs separate divisions of the bar (1 to 9) for the three contrapuntal parts, using a scheme of shaped noteheads to visually clarify the differences, but the pioneering of these signatures is largely due to Brian Ferneyhough, who says that he finds that "such 'irrational' measures serve as a useful buffer between local changes of event density and actual changes of base tempo".

[19] Thomas Adès has also used them extensively—for example in Traced Overhead (1996), the second movement of which contains, among more conventional meters, bars in such signatures as 26, 914 and 524.

[citation needed] For example, John Pickard's Eden, commissioned for the 2005 finals of the National Brass Band Championships of Great Britain, contains bars of 310 and 712.

These video samples show two time signatures combined to make a polymeter, since 43, say, in isolation, is identical to 44.

Some composers have used fractional beats: for example, the time signature 2+1⁄24 appears in Carlos Chávez's Piano Sonata No.

Music educator Carl Orff proposed replacing the lower number of the time signature with an actual note image, as shown at right.

The relation between the breve and the semibreve was called tempus, and could be perfect (triple 3:1 indicated by circle) or imperfect (duple 2:1, with broken circle), while the relation between the semibreve and the minim was called prolatio and could be major (3:1 or compound, indicated by dot) or minor (2:1 or simple meter).

By the end of the sixteenth century Thomas Morley was able to satirize the confusion in an imagined dialogue: it was a world to hear them wrangle, every one defending his own for the best.

"Nay, you sing you know not what; it would seem you came lately from a barber's shop where you had 'Gregory Walker' or a Curranta played in the new Proportions by them lately found out, called 'Sesquiblinda' and 'Sesquihearkenafter'."

4 at 60 bpm

4 at 60 bpm

4 at 60 bpm

8 at 120 bpm

4 and 4

3 played together has three beats of 4

3 to four beats of 4

4

6 and 3

4 played together has six beats of 2

6 to four beats of 3

4

5 and 2

3 played together has five beats of 2

5 to three beats of 2

3 . The displayed numbers count the underlying polyrhythm , which is 5:3

8 and 6

8 respectively)