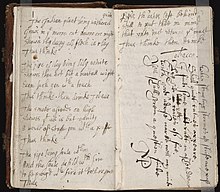

Commonplace book

Such books are similar to scrapbooks filled with items of many kinds: notes, proverbs, adages, aphorisms, maxims, quotes, letters, poems, tables of weights and measures, prayers, legal formulas, and recipes.

[2] "Commonplace" is a translation of the Latin term locus communis (from Greek tópos koinós, see literary topos) which means "a general or common place", such as a statement of proverbial wisdom.

Commonplaces are used by readers, writers, students, and scholars as an aid for remembering useful concepts or facts; sometimes they were required of young women as evidence of their mastery of social roles and as demonstrations of the correctness of their upbringing.

Locke gave specific advice on how to arrange material by subject and category, using such key topics as love, politics, or religion.

The gentlewoman Elizabeth Lyttelton kept one from the 1670s to 1713[5] and a typical example was published by Mrs Anna Jameson in 1855,[6] including headings such as Ethical Fragments; Theological; Literature and Art.

[11] As a result of the development of information technology, there exist various software applications that perform the functions that paper-based commonplace books served for previous generations of thinkers.

While there are ancient compilations by writers including Pliny and Diogenes Laertius, many authors in the Renaissance credited Aulus Gellius as the founder of the genre with his commonplace Attic Nights.

By the eighth century, the idea of commonplaces was used, primarily in religious contexts, by preachers and theologians, to collect excerpted passages from the Bible or from approved Church Fathers.

Precursors to the commonplace book were the records kept by Roman and Greek philosophers of their thoughts and daily meditations, often including quotations from other thinkers.

The practice of keeping a journal such as this was particularly recommended by Stoics such as Seneca and Marcus Aurelius, whose own work Meditations (second century AD) was originally a private record of thoughts and quotations.

[18] Zibaldone were always paper codices of small or medium format – never the large desk copies of registry books or other display texts.

The juxtaposition of taxes paid, currency exchange rates, medicinal remedies, recipes, and favourite quotations from Augustine and Virgil portrays a developing secular, literate culture.

[20] By far the most popular literary selections were the works of Dante Alighieri, Francesco Petrarca, and Giovanni Boccaccio: the "Three Crowns" of the Florentine vernacular traditions.

Some, such as Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Mark Twain, and Virginia Woolf kept messy reading notes that were intermixed with other quite various material; others, such as Thomas Hardy, followed a more formal reading-notes method that mirrored the original Renaissance practice more closely.