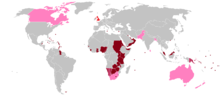

Commonwealth realm

The notion of these states sharing the same person as their monarch traces back to 1867 when Canada became the first dominion, a self-governing nation of the British Empire; others, such as Australia (1901) and New Zealand (1907), followed.

[1] The Statute of Westminster 1931 further set the relationship between the realms and the Crown, including a convention that any alteration to the line of succession in any one country must be voluntarily approved by all the others.

They are united only in their voluntary connection with the institution of the monarchy,[1] the succession, and the King himself; the person of the sovereign and the Crown were said in 1936 to be "the most important and vital link" between the dominions.

[9] Political scientist Peter Boyce called this grouping of countries associated in this manner "an achievement without parallel in the history of international relations or constitutional law.

[35] Since each realm has the same person as its monarch, the diplomatic practice of exchanging ambassadors with letters of credence and recall from one head of state to another does not apply.

[3][41][28] From a cultural standpoint, the sovereign's name, image and other royal symbols unique to each nation are visible in the emblems and insignia of governmental institutions and militia.

Elizabeth II's effigy, for example, appears on coins and banknotes in some countries, and an oath of allegiance to the King is usually required from politicians, judges, military members and new citizens.

[44] To guarantee the continuity of multiple states sharing the same person as monarch, the preamble of the Statute of Westminster 1931 laid out a convention that any alteration to the line of succession in any one country must be voluntarily approved by the parliaments of all the realms.

[46] Sir Maurice Gwyer, first parliamentary counsel in the UK, reflected this position, stating that the Act of Settlement was a part of the law in each dominion.

[46] Though today the Statute of Westminster is law only in Canada, Australia and the United Kingdom,[47] the convention of approval from the other realms was reasserted by the Perth Agreement of 2011, in which all 16 realms at the time agreed in principle to change the succession rule to absolute primogeniture, to remove the restriction on the monarch being married to a Catholic, and to reduce the number of members of the Royal Family who need the monarch's permission to marry.

[note 11] Following the accession of George VI to the throne, the United Kingdom created legislation that provided for a regency if the monarch was not of age or incapacitated.

These appointments are made on the advice of the prime minister of the country or the premier of the province or state concerned, though this process may have additional requirements.

The preamble to the Statute of Westminster 1931 established the convention requiring the consent of all the dominions' parliaments, as well as that of the United Kingdom, to any alterations to the monarch's style and title.

All that was agreed at the Commonwealth Prime Ministers' Conference in 1949 was that each of George VI's countries should have a different title, but with common elements, and it would be sufficient for each realm's parliament to pass a local law.

[74] Queen Elizabeth II employed various royal standards to mark her presence, the particular one used depending on which realm she was in or acting on behalf of at the time.

[82] This unitary model began to erode when the dominions gained more international prominence as a result of their participation and sacrifice in the First World War.

In 1921 the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, David Lloyd George, stated that the "British dominions have now been accepted fully into the community of nations".

[88][83][89] Another catalyst for change came in 1926, when Field Marshal the Lord Byng of Vimy, then Governor General of Canada, refused the advice of his prime minister (William Lyon Mackenzie King) in what came to be known colloquially as the King–Byng Affair.

At the same time, terminology in foreign relations was altered to demonstrate the independent status of the dominions, such as the dropping of the term "Britannic" from the King's style outside of the United Kingdom.

[97] Specific attention was given in the statute's preamble to royal succession, outlining that no changes to that line could be made by the parliament of the United Kingdom or that of any dominion without the assent of all the other parliaments of the UK and dominions, an arrangement a justice of the Ontario Superior Court in 2003 likened to "a treaty among the Commonwealth countries to share the monarchy under the existing rules and not to change the rules without the agreement of all signatories".

[98] This was all met with only minor trepidation, either before or at the time,[note 16] and the government of the Irish Free State was confident that the relationship of these independent countries under the Crown would function as a personal union,[20] akin to that which had earlier existed between the United Kingdom and Hanover (1801 to 1837), or between England and Scotland (1603 to 1707).

Afterward, Francis Floud, Britain's high commissioner to Canada, opined that the whole affair had strengthened the connections between the various nations; though, he felt the Crown could not suffer another shock.

[101] As the various legislative steps taken by the dominions resulted in Edward abdicating on different dates in different countries, this demonstrated the division of the Crown post-Statute of Westminster.

British Prime Minister Winston Churchill was told "His Majesty is genuinely alarmed at the feeling, which appears to be growing in Australia and may well be aggravated by further reverses in the Far East.

Further, at her coronation, Elizabeth II's oath contained a provision requiring her to promise to govern according to the rules and customs of the realms, naming each one separately.

The change in perspective was summed up by Patrick Gordon Walker's statement in the British House of Commons: "We in this country have to abandon... any sense of property in the Crown.

Lord Altrincham, who in 1957 criticised Queen Elizabeth II for having a court that encompassed mostly Britain and not the Commonwealth as a whole,[121] was in favour of the idea, but it did not attract wide support.

The prime ministers of Canada and Australia, John Diefenbaker and Robert Menzies, respectively, were sympathetic to the concept, but, again, it was never put into practice.

[124] The following year, Portia Simpson-Miller, the Prime Minister of Jamaica, spoke of a desire to make that country a republic,[125][126] while Alex Salmond, the First Minister of Scotland and leader of the Scottish National Party (which favours Scottish independence), stated an independent Scotland "would still share a monarchy with ... the UK, just as ... 16 other [sic] Commonwealth countries do now.

[137][138] In 2022, following the death of Elizabeth II and the accession of Charles III, the governments of Jamaica,[139] The Bahamas,[140] and Antigua and Barbuda[141] announced their intentions to hold referendums.