Communist Party of New Zealand

Although spurred to life by events in Soviet Russia in the aftermath of World War I, the party had roots in pre-existing revolutionary socialist and syndicalist organisations, including in particular the independent Wellington Socialist Party, supporters of the Industrial Workers of the World in the Auckland region, and a network of impossiblist study groups of miners on the west coast of the South Island.

A. Wayland, proprietor of the mass circulation socialist weekly Appeal to Reason, detailed the ways in which the island nation of 720,000 had already passed extensive legislation for the benefit of wage workers, backed by 200 agents of the "Labour Intelligence Department".

[5] The presence of "tramps" had been eliminated through town allotments of small homesteads to poor workers, granted through easily affordable perpetual leases.

[8] The national government itself owned and operated the railways, telegraph and telephone systems, schools, and postal savings banks throughout the country even before the landmark election of 1891.

[10] Richard Seddon (1845–1906), Prime Minister of New Zealand from 1893 until his death in 1906, oversaw implementation of an array of social welfare programs as leader of the Liberal Government This idyllic vision – which incidentally paid no attention to the treatment of or conditions endured by the indigenous Polynesian population – proved to be short-lived.

The New Zealand Socialist Party (NZSP), founded in 1901, included in its ranks a left wing which eschewed political action, arguing that socialism could only be won by the direct efforts of the organised working class acting through their unions.

[15] Wartime violence and the 1917 October Revolution in Russia proved a stimulant to revolutionary ideas, drawing members to these groups, leading to their formal affiliation during the summer Christmas holiday of 1918 as the New Zealand Marxian Association (NZMA).

[15] This group electing T. W. Feary as secretary of the organisation and in 1919 dispatched him and two others to North America to gain additional information on the revolutionary movement through the American and Canadian prism.

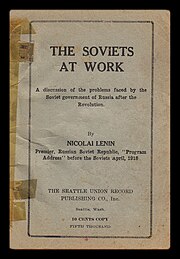

[15] Visiting the Pacific Coast cities of San Francisco and Vancouver, Feary and his co-thinkers obtained copies of a number of influential publications, including Ten Days That Shook the World, a participant's account of the October Revolution by John Reed, and The Soviets at Work, a widely reprinted pamphlet by Vladimir Lenin.

[15] Adding to the complexity of the fragmented radical movement was the Wellington Socialist Party, formerly a branch of the NZSP which had split with the national organisation in 1913 over the issue of electoral politics.

[15] In contrast to demographic findings made of the early Communist Party of America, for example, the communist movement in New Zealand was never dominated by Slavic, Scandinavian, and Jewish emigrants from the former Russian empire, with one academic study showing that a big majority of the movement's participants during the decade of the 1920s were either native New Zealanders by birth or first-generation immigrants from England, Scotland, Ireland, or Wales.

[15] Unable to take over the newspaper of the Federation of Labour, the Maoriland Worker, in 1924 the CPNZ established its own official publication, The Communist, published in Auckland.

[19] Despite the establishment of this new central organ, the organisation remained highly decentralised in its formative years, with branches operating in virtual isolation and the small movement failing to achieve critical mass.

[21] This situation continued through all of 1925, only ending the year after following a six-month organising tour by Australian activist Norman Jeffrey,[20] a bow-tie wearing former "Wobbly" (IWW member).

[21] In April 1926 a new monthly magazine was launched for the New Zealand communist movement, The Workers' Vanguard, published in the isolated inland mining town of Blackball, located on the rainy West Coast side of the South Island.

[23] Twenty-eight-year-old Wellington activist Dick Griffin, a member of the Seamen's Union, was chosen as the party's first-ever delegate to a Comintern gathering in Moscow.

[23] The 6th Congress of the Comintern is remembered for its launch of the ultra-radical analysis and tactics of the so-called Third Period, which posited the rapid decay of capitalism and the acceleration of the class struggle and coming of potential revolutionary situations.

The CPNZ was beset by rapid membership turnover throughout the late 1920s and early 1930s, with general secretary Griffin accused of operating a personal dictatorship, spurring rank-and-file discontent.

[30] By the middle of 1933, the Communist Party of New Zealand was in crisis, with its entire Central Committee jailed for publication of the pamphlet Karl Marx and the Struggle of the Masses.

[31] The New Zealand-born Fred Freeman was returned to the country to assume the position of general secretary following four years in Moscow at the service of the Comintern.

[31] Dues collecting and record-keeping of branches was made more regular and increased attention was paid to the problem of internal security in an effort to stave the crippling series of arrests that had swept the party.

[32] Comintern policy began to change in 1933 following the victory of the Nazi Party in Germany, leading to eventual advocacy of a so-called Popular Front against fascism by 1935.

[34] The CPNZ responded to the tacit rejection of their appeal by accelerating their efforts to drive a wedge between the rank and file and leadership of each of these organisations, a tactic euphemistically called the "United Front from Below.

[37] Dissatisfaction with Freeman's commanding leadership style grew in 1935 and 1936 and he landed on the wrong side of the Popular Front-driven Comintern decision that the CPNZ should seek formal affiliation with the Labour Party sooner rather than later.

[43] The Communist Party experienced the loss of several prominent members including Sid Scott following Nikita Khrushchev's denunciation of Stalin at the 20th Congress of the CPSU in February 1956 and the Soviet suppression of the Hungarian Revolution in November 1956.

[44] As a result of these events, most of the intellectuals the CPNZ had attracted left the party while some erstwhile supporters founded new journals such as New Zealand Monthly Review, Comment, Socialist Forum, and Here & Now.

[44] While the CPNZ never had mass influence or real political power, it pursued a Leninist vanguard party approach that involved trying to influence and penetrate the Labour Party, the New Zealand trade union movement, various single-issue protest groups and public opinion on foreign policy, industrial activity, opposition to New Zealand's involvement in the Vietnam War, Māori rights, the anti-Apartheid movement, feminism, and nuclear disarmament, and anti-colonial activism in the Pacific region; issues in which communists and non-communist left-wing elements found common cause.