Community-acquired pneumonia

In contrast, hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP) is seen in patients who have recently visited a hospital or who live in long-term care facilities.

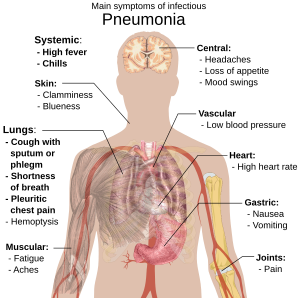

CAP is common, affecting people of all ages, and its symptoms occur as a result of oxygen-absorbing areas of the lung (alveoli) filling with fluid.

CAP, the most common type of pneumonia, is a leading cause of illness and death worldwide[citation needed].

Patients with CAP sometimes require hospitalization, and it is treated primarily with antibiotics, antipyretics and cough medicine.

Alcoholics and others with compromised immune systems are more likely to develop CAP from Haemophilus influenzae or Pneumocystis jirovecii.

[12] Typically, a virus enters the lungs through the inhalation of water droplets and invades the cells lining the airways and the alveoli.

White blood cells, particularly lymphocytes, activate chemicals known as cytokines which cause fluid to leak into the alveoli.

The immune system responds by releasing neutrophil granulocytes, white blood cells responsible for attacking microorganisms, into the lungs.

The neutrophils, bacteria and fluids leaked from surrounding blood vessels fill the alveoli, impairing oxygen transport.

Bacteria may travel from the lung to the bloodstream, causing septic shock (very low blood pressure which damages the brain, kidney, and heart).

They then travel to the lungs through the blood, where the combination of cell destruction and immune response disrupts oxygen transport.

[15] When signs of pneumonia are discovered during evaluation, chest X-rays and examination of the blood and sputum for infectious microorganisms may be done to support a diagnosis of CAP.

The diagnostic tools employed will depend on the severity of illness, local practices and concern about complications of the infection.

[citation needed] CAP may be prevented by treating underlying illnesses that increases its risk, by smoking cessation, and by vaccination.

Vaccination against Haemophilus influenzae and Streptococcus pneumoniae in the first year of life has been protective against childhood CAP.

Additional consideration is given to the treatment setting; most patients are cured by oral medication, while others must be hospitalized for intravenous therapy or intensive care.

Current treatment guidelines recommend a beta-lactam, like amoxicillin, and a macrolide, like azithromycin or clarithromycin, or a quinolone, such as levofloxacin.

Ceftriaxone and azithromycin are often used to treat community-acquired pneumonia, which usually presents with a few days of cough, fever, and shortness of breath.

[19] Most newborn infants with CAP are hospitalized, receiving IV ampicillin and gentamicin for at least ten days to treat the common causative agents Streptococcus agalactiae, Listeria monocytogenes and Escherichia coli.

If hospitalization is not required, a seven-day course of amoxicillin is often prescribed, with co-trimaxazole as an alternative when there is allergy to penicillins.

[22] In 2001 the American Thoracic Society, drawing on the work of the British and Canadian Thoracic Societies, established guidelines for the management of adult CAP by dividing patients into four categories based on common organisms:[23] For mild-to-moderate CAP, shorter courses of antibiotics (3–7 days) seem to be sufficient.

Some recent research focuses on immunomodulatory therapy that can modulate the immune response in order to reduce injury to the lung and other affected organs such as the heart.

[27] Some CAP patients require intensive care, with clinical prediction rules such as the pneumonia severity index and CURB-65 guiding the decision whether or not to hospitalize.

[31] Patients with underlying illnesses (such as Alzheimer's disease, cystic fibrosis, COPD, tobacco smoking, alcoholism or immune-system problems) have an increased risk of developing pneumonia.