Computational physics

[2] In physics, different theories based on mathematical models provide very precise predictions on how systems behave.

Unfortunately, it is often the case that solving the mathematical model for a particular system in order to produce a useful prediction is not feasible.

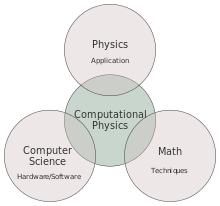

[4] Sometimes it is regarded as more akin to theoretical physics; some others regard computer simulation as "computer experiments",[4] yet still others consider it an intermediate or different branch between theoretical and experimental physics, a third way that supplements theory and experiment.

This is due to several (mathematical) reasons: lack of algebraic and/or analytic solvability, complexity, and chaos.

For example, even apparently simple problems, such as calculating the wavefunction of an electron orbiting an atom in a strong electric field (Stark effect), may require great effort to formulate a practical algorithm (if one can be found); other cruder or brute-force techniques, such as graphical methods or root finding, may be required.

Finally, many physical systems are inherently nonlinear at best, and at worst chaotic: this means it can be difficult to ensure any numerical errors do not grow to the point of rendering the 'solution' useless.