Computer font

A computer font is implemented as a digital data file containing a set of graphically related glyphs.

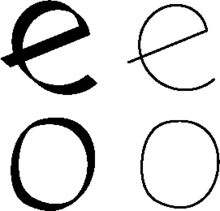

In the terminology of movable metal type, a typeface is a set of characters that share common design features across styles and sizes (for example, all the varieties of Gill Sans), while a font is a set of pieces of movable type in a specific typeface, size, width, weight, slope, etc.

In HTML, CSS, and related technologies, the font family attribute refers to the digital equivalent of a typeface.

For example, if a font has three sizes, and any combination of bold and italic, then there must be 12 complete sets of images.

The limited processing power and memory of early computer systems forced the exclusive use of bitmap fonts.

For example, the original Apple Macintosh computer could produce bold by widening vertical strokes and oblique by shearing the image.

At non-native sizes, many text rendering systems perform nearest-neighbor resampling, introducing rough jagged edges.

The advent of desktop publishing brought the need for a common standard to integrate the graphical user interface of the first Macintosh and laser printers.

The converse transformation is considerably harder since bitmap fonts require a heuristic algorithm to guess and approximate the corresponding curves if the pixels do not make a straight line.

[2] Measures such as font hinting have to be used to reduce the visual impact of this problem, which requires sophisticated software that is difficult to implement correctly.

Despite this, they are frequently used because people often consider the ability to freely scale fonts, without incurring any pixelation, to be important enough to justify the defects and increased computational complexity.

These issues are however mostly solved by antialiasing (as described in font rasterization) and the high display resolutions that are commonly in use today.

Although Monotype and Bitstream have claimed tremendous space saving using stroke-based fonts on East Asian character sets, most of the space saving comes from building composite glyphs, which is part of the TrueType specification and does not require a stroke-based approach.

Type 1 fonts were restricted to a subset of the PostScript language, and used Adobe's hinting system, which used to be very expensive.

Type 3 allowed unrestricted use of the PostScript language, but did not include any hint information, which could lead to visible rendering artifacts on low-resolution devices (such as computer screens and dot-matrix printers).

Unlike Type 1 fonts, TrueType glyphs are described with quadratic Bézier curves.

A typical font may contain hundreds or even thousands of glyphs, often representing characters from many different languages.