Concealing-Coloration in the Animal Kingdom

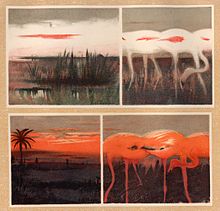

Thayer rejected Charles Darwin's theory of sexual selection, arguing in words and paintings that even such conspicuous animal features as the peacock's tail or the brilliant pink of flamingoes or roseate spoonbills were effective as camouflage in the right light.

The book introduced the concepts of disruptive coloration to break up an object's outlines, of masquerade, as when a butterfly mimics a leaf, and especially of countershading, where an animal's tones make it appear flat by concealing its self-shadowing.

The book was criticised by big game hunter and politician Theodore Roosevelt for its central assertion that every aspect of animal coloration is effective as camouflage.

Roosevelt's detailed reply attacked the biased choice of examples to suit Abbott Thayer's thesis and the book's reliance on unsubstantiated claims in place of evidence.

[4][5] The same obsession led him, later, to attempt to persuade the military to adopt camouflage based on his ideas, traveling to London in 1915, and writing "passionate letters" to the Assistant Secretary to the US Navy, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, in 1917.

[P 1] The book has 16 colored plates of paintings by Abbott Thayer and Richard S. Meryman, including the well known frontispiece "Peacock amid foliage", and the heavily criticised images of wood ducks, blue jays against snow, roseate spoonbills and flamingoes "at dawn or sunset, and the skies they picture".

Thayer distinguishes "concealing-colors" (mainly countershading for "invisibility") from the "other" branch of protective coloration, which includes most kinds of mimicry, for "deceptive visibility".

Thayer describes these as showing "obliteration, or merging with the background" but that their patterning is close to mimicry as they "perfectly" resemble objects such as "a stone or mossy log".

Thayer attempts to classify the camouflage types, for example writing The principal feature of the pattern made by grasses over ground is a more or less intricate lace-work of crisscrossing, light-colored, linear forms, some straight, some curled and twisted, relieving with varying intensity against dark.Chapter 8 continues the theme with "scansorial" or tree climbing birds.

Chapter 10 describes the "background-picturing" of bitterns, birds which live in reedbeds, where The light stripes on the bill were repeated and continued by the light stripes on the sides of the head and neck, and together they imitated very closely the look of separate, bright reed-stems; while the dark stripes pictured reeds in shadow, or the shadowed interstices between the stems.Chapter 11 argues (in a way that was heavily criticised when the book appeared, see below) that water birds, some of them highly conspicuous like the jacana and notoriously the male wood duck, are colored for camouflage: "The beautifully contrasted black-and-white bars on the flanks of the Wood Duck (Aix sponsa) are ripple pictures, and as potent [as camouflage], in their place, as the most elaborate markings of land birds".

Thayer admits that these often appear conspicuous, but argues that against varied backgrounds, white offers "the greatest average inconspicuousness against the ocean" (his italics) or against the bright sky when seen from below.

Using a photograph of an oystercatcher at its nest by Cherry and Richard Kearton, Thayer argues that the boldly marked bird (mainly black above, white below, with red beak) is both countershaded and "ruptively" patterned.

Chapter 14 discusses the barred markings of hawks and owls, with further fine plates of photographs by the Keartons of disruptively patterned waders and their cryptic chicks.

Chapter 16 controversially claims that the iridescent colours of, for example, the speculum wing patch of the mallard and other ducks is "obliterative", the "brightly changeable plumage" serving to camouflage the wearer in varying conditions.

Chapter 18 briefly discusses mimicry, before returning to "the evident paramount importance of the obliterative function", this time of the "brilliant, flowerlike" heads of hummingbirds.

The one case that Thayer admits is mimetic is the goatsucker of Trinidad, a plant mimic that perches "by day and night" on a tree stump or branch, where the purpose of the mimicry is crypsis.

Thayer notes that a few species with strong defences[6] such as hedgehogs, porcupines, echidnas, pangolins and "some armadillos" are exceptions, along with some beasts which "enjoy a like security by virtue of their gigantic bigness", including the elephants, rhinoceroses, and hippopotamuses.

The domestic hare is shown to be strongly countershaded with a pair of photographs "from life", one sitting and one "laid on its back, outdoors, so that the obliterative shading is reversed".

These are "triumphs of art", where the student can find "in epitome, painted and perfected by Nature herself", the typical color and pattern scheme of each kind of landscape.

The Thayers' views were vigorously criticised in 1911 by Theodore Roosevelt, an experienced big game hunter[8] and naturalist familiar with animal camouflage as well as a politician, in a lengthy article in the Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History.

[14] Thayer was also roundly criticised in 1911 by herpetologist Thomas Barbour and conservation pioneer John C. Phillips[15] in The Auk, where they wrote that[16] Mr. Thayer, however, along with most other enthusiasts in a field with which they can be but partially familiar, has gone too far and claimed too much.Barbour and Phillips warmly welcome Thayer's work on countershading "which he has so excellently demonstrated"; they "protest gently" against his "slightly patronizing" treatment of the camouflage of birds like woodcock and grouse "which has been known and recognized since ornithology began"; and go on to the attack on his claims for the flamingo:[16] Flamingoes hardly need this carefully arranged protection that is of value but a few minutes each day, and to be sure we see the curious cloud arrangement depicted on but very few days of the year – if ever.They are equally critical of his roseate spoonbill, observing that the painting looks nothing like "actual skins of the species".

[16] The English ornithologists Douglas Dewar and Frank Finn write in their 1909 book The Making of Species that Thayer "seems to be of opinion that all animals are cryptically or, as he calls it, concealingly or obliteratively coloured".

[20] He then lists the cases of the white flamingo, the skunk and the white rump of the prongbuck, quoting Roosevelt ("The raven's coloration is of course concealing if it is put into a coal scuttle"[20]), notes "How unreasonable are extreme views like that adopted by Thayer",[20] and admits that criticisms of "certain of Thayer's conclusions"[20] are justified, before returning to the attack on those critics, robustly defending the "theory of protective and aggressive resemblance".

[21] The evolutionary biologist John Endler, reviewing the topic of camouflage in Proceedings of the Royal Society B in 2006, cites Thayer's 1909 book three times: for disruption, with "conspicuous elements [which] distract the predator's attention and break up the body outline, making detection of the prey difficult";[22] for "masquerade, [where] the prey is detected as distinct from the visual background but not recognized as edible.., for example by resembling a leaf";[22] and for countershading, where "False gradients are common in animal colour patterns, leading to misleading appearance of shape, even when they do not disrupt the body outline".

[23] The art and science writer Peter Forbes notes that Thayer became obsessed by the "flattening effect" of countershading, and that far from being a scientist, he was "an artist whose idealist fervour, edged by deep insecurity, led him to regard his findings less as discovery than as revelation.

"[22] Describing Concealing-Coloration as a "magnum opus",[22] Forbes writes that by 1909 "Thayer's prophetic intolerance was in full flood",[22] that he was overcompensating for his need for approval of his artwork, and that he failed to see that acceptance of ideas in science does not depend on "the vehemence with which they are expressed".

[22] The philosopher and jazz musician David Rothenberg, in his 2012 book Survival of the Beautiful on the relationship between aesthetics and evolution,[24] argues that while the Thayers' book set out the principles of camouflage: "From observation of nature ... art contributed to the military needs of society", Thayer, following Charles Darwin, was "swept up in the idea that every animal had evolved to perfectly live in its surroundings", but was emotionally unable to accept the other "half" of Darwin's view of animal coloration:[25] Thayer was quite troubled by Darwin's whole notion of sexual selection to explain the evolution of taste and beauty... On the contrary, all animal patterning can be explained by the need to remain .. hidden..

He explains that the Thayers believed they, "trained as artists", had seen what earlier observers had missed:[26] The black and white patches and stripes are 'ripple pictures depicting motion and reflections in the water', all ingeniously evolved to hide the bird not by inconspicuousness but by 'disruptive conspicuousness'.The Smithsonian American Art Museum's website, describing the Thayers' book as "controversial", writes sceptically that[27] Even bright pink flamingoes would vanish against a similar colored sky at sunset or sunrise.

No matter that at times their brilliant feathers were highly visible, their coloration would protect them from predators at crucial moments so that "the spectator seems to see right through the space occupied by an opaque animal."