The Naturalist on the River Amazons

In 1847, Bates and his friend Alfred Russel Wallace, both in their early twenties,[a] agreed that they would jointly make a collecting trip to the Amazon "towards solving the problem of origin of species".

Wallace sailed back to England in 1852 after four years; on the voyage, his ship caught fire, and his collection was destroyed; undeterred, he set out again, leading eventually (1869) to a comparable book, The Malay Archipelago.

The style is accurate, but vivid and direct: The house lizards belong to a peculiar family, the Geckos, and are found even in the best-kept chambers, most frequently on the walls and ceilings, to which they cling motionless by day, being active only at night.

The structure of their feet is beautifully adapted for clinging to and running over smooth surfaces; the underside of their toes being expanded into cushions, beneath which folds of skin form a series of flexible plates.

By means of this apparatus they can walk or run across a smooth ceiling with their backs downwards; the plated soles, by quick muscular action, exhausting and admitting air alternately.

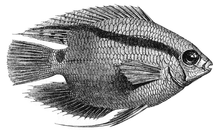

Amongst these masses I espied many fruits of that peculiarly Amazonian tree the Ubussu palm; this was the last I saw of the Great River.There are 39 illustrations, some of animals and plants, some of human topics such as the "Masked-dance and wedding-feast of Tucuna Indians", which is signed by Josiah Wood Whymper.

[11] The structure of the readable, cut-down second edition of 1864 is as follows: The impressions received during this first walk can never wholly fade from my mind... Amongst them were several handsome women, dressed in a slovenly manner, barefoot or shod in loose slippers; but wearing richly-decorated ear-rings, and around their necks strings of very large gold beads.

It was a mere fancy, but I thought the mingled squalor, luxuriance and beauty of these women were pointedly in harmony with the rest of the scene; so striking, in the view, was the mixture of natural riches and human poverty.At mid-day the vertical sun penetrates into the gloomy depths of this romantic spot, lighting up the leafy banks of the rivulet and its clean sandy margins, where numbers of scarlet, green, and black tanagers and brightly-coloured butterflies sport about in the stray beams.

— John Gould, painter and ornithologist[4]...the power of observation and felicity of style which characterizes The Naturalist on the Amazons — Alfred Russel Wallace[12]Charles Darwin, having encouraged Bates to publish an account of his travels, read The Naturalist on the River Amazons with great pleasure, writing to Bates on 18 April 1863 that My criticisms may be condensed into a single sentence, namely that it is the best book of Natural History Travels ever published in England.

Darwin at once observes that although Bates is "no mean authority" on insects, the book is not limited to them, but ranges over natural history and more widely to describe his "adventures during his journeyings up and down the mighty river".

But in very few has it happened that the species which clearly appears to be the parent, co-exists with one that has been evidently derived from it.The London Quarterly Review began with the observation that "When an intelligent man tells us that he has spent eleven of the best years of his life in any district, we may be pretty sure he has something to say about it which will interest even those who generally find travels dull reading".

In the reviewer's opinion, Bates says little about "the Darwinian hypothesis", focusing instead steadily on natural history, while making "very shrewd remarks" about human society and giving "most glowing" descriptions of tropical scenery.

The reviewer notes that most of the people Bates meets "had a tinge of colour" but made the "lonely Englishman" comfortable with their "winning cordiality", and is amused that in a feast in Ega an Indian dressed up as an entomologist, complete with insect-net, hunting-bag, pincushion, and an old pair of spectacles.

However the reviewer is fascinated by the variety of life described in the book, and by Bates's "rapturous manner" of speaking about how delicious monkey flesh is, which "almost puts a premium on cannibalism".

"James spends much space in his review quoting Bates's account of the strangling fig, called the "Murderer Liana or Sipo", which he uses to emphasize the "struggle for existence" between plants, as much as for animals.

"[4] He feels a dreamy quality in the best of Bates's writing, as when he meets a boa constrictor: "On seeing me the reptile suddenly turned, and glided at an accelerated rate down the path.

He celebrates the "famous closing passage" of the book, where Bates expresses his "deep misgivings" about returning to England, and writes that recent "progress" in the Amazon is just as shocking.

Noting that Bates collected over 8,000 species on the trip, the book shows, writes Anderson, how this was achieved:[18] the discomfort of narrow canoes, the encounters with alligators and giant spiders, drinking burning rum around a campfire while waiting for jaguars, and above all else the sheer fun and intense joy of seeing new things in new places through eyes of a keen observer and master storyteller..The Zoological Society of London writes that "This fascinating, lucidly written book is widely regarded as one of the greatest reports of natural history travels."

"[11] Bates's book is cited in papers for its accurate early observations, such as of the urticating hairs of tarantulas,[19] the puddle drinking habits of butterflies,[20] or of the rich insect fauna in the tropics.