Concentrated animal feeding operation

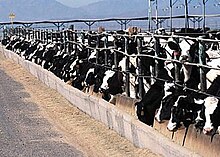

CAFOs are commonly characterized as having large numbers of animals crowded into a confined space, a situation that results in the concentration of manure in a small area.

The most common type of facility used in these plans, the anaerobic lagoon, has significantly contributed to environmental and health problems attributed to the CAFO.

[12] States with high concentrations of CAFOs experience on average 20 to 30 serious water quality problems per year as a result of manure management issues.

North Carolina contains a lot of the United States' industrial hog operations, which disproportionally impact Black, Hispanic and Indian American residents.

[29] Greenhouse gases and climate change make air worse, causing illnesses such as respiratory disorders, lung tissue damage, and allergies.

[31] Also, people near CAFOs often complain of the smell, which comes from a complex mixture of ammonia, hydrogen sulfide, carbon dioxide, and volatile and semi-volatile organic compounds.

The spray can be carried by wind onto nearby homes, depositing pathogens, heavy metals, and antibiotic resistant bacteria into the air of poor or minority communities.

[39] The development of new technologies has also helped CAFO owners reduce production cost and increase business profits with less resources consumption.

Many farmers in the United States find that it is difficult to earn a high income due to the low market prices of animal products.

Alternative animal production methods, like "free range" or "family farming" operations[42] are losing their ability to compete, though they present few of the environmental and health risks associated with CAFOs.

[5] The costs from damage caused to the atmosphere (in the form of GHGs), water, soil, fisheries, and recreational areas, estimated at hundreds of billions of dollars, are typically not incurred by corporations that feature the use of CAFOs in their business models.

[50] The direct discharge of manure from CAFOs and the accompanying pollutants (including nutrients, antibiotics, pathogens, and arsenic) is a serious public health risk.

[53] High levels of nitrate in drinking water are associated with increased risk of hyperthyroidism, insulin-dependent diabetes, and central nervous system malformations.

This threatens public health because resistant bacteria generated by CAFOs can be spread to the surrounding environment and communities via waste water discharge or the aerosolization of particles.

[61] Furthermore, a Dutch cross-sectional study 2,308 adults found decreases in residents' lung function to be correlated with increases of particle emissions by nearby farms.

[56] In addition, individuals working in CAFOs are at risk for chronic airway inflammatory diseases secondary to dust exposure, with studies suggesting the possible benefits to utilizing inhaler treatments empirically.

Black and brown people living near CAFOs often lack the resources to leave compromised areas and are further trapped by plummeting property values and poor quality of life.

According to David Nibert, professor of sociology at Wittenberg University, more than 10 billion animals are housed in "horrific conditions" in more than 20,000 CAFOs across the U.S. alone, where they "spend their last 100–120 days crammed together by the thousands standing in their own excrement, with little or no shelter from the elements.

[86] It specifically defines CAFOs as point source polluters and required operations managers and/or owners to obtain NPDES permits in order to legally discharge wastewater from its facilities.

Specifically, the EPA adopted the following measures: The 2008 final rule also specifies two approaches that a CAFO may use to identify the "annual maximum rates of application of manure, litter, and process wastewater by field and crop for each year of permit coverage."

The linear approach expresses the rate in terms of the "amount of nitrogen and phosphorus from manure, litter, and process wastewater allowed to be applied."

As a result, CAFO operators can more easily "change their crop rotation, form and source of manure, litter, and process wastewater, as well as the timing and method of application" without having to seek a revision to the terms of their NPDES permits.

[112] Lastly, the EPA notes that the USDA offers a "range of support services," including a long-term program that aims to assist CAFOs with NMPs.

Researchers have identified regions in the country that have weak enforcement of regulations and, therefore, are popular locations for CAFO developers looking to reduce cost and expand operations without strict government oversight.

"[121] Some of the agricultural industry groups continue to maintain that the EPA should have no authority to regulate any of the runoff from land application areas because they believe this constitutes a nonpoint source that is outside the scope of the CWA.

[124] This protection includes all waterways, whether or not the water body can safely sustain aquatic life or house public recreational activities.

For instance, in 2008, Illinois Citizens for Clean Air & Water filed a complaint with the EPA arguing that the state was not properly implementing its CAFO permitting program.

In a report released in 2010, the agency sided with the environmental organization and provided a list of recommendations and required action for the state to meet.

Some of these states (such as Iowa, Oklahoma, Wyoming, Tennessee, and Kansas) also provide specific protection to animal feeding operations (AFOs) and CAFOs.

[131][dead link] The petition alleges that "CAFOs are leading contributors to the nation's ammonia inventory; by one EPA estimate livestock account for approximately 80 percent of total emissions.