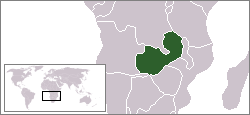

Congo Pedicle

From the British point of view, the obvious choice for the border would have been southwest to northeast line from the watershed to the Luapula.

[4] But the Belgians hoped for access to the rich game areas of the Bangweulu Wetlands and pressed for the borders to stick to the river and watershed.

The agreement was incorporated into this larger treaty between Great Britain and King Leopold II, which dealt mainly with Equatoria.

The Italian king's ruler was moved west to a point where it did cut a clearly defined channel in one place.

It was the BSAC's failure to get Msiri to sign up Garanganza as a British protectorate which lost the Congolese Copperbelt to Northern Rhodesia, and some in the BSAC complained that the British missionaries Frederick Stanley Arnot and Charles Swan could have done more to help, although their Plymouth Brethren mission had a policy of not being involved in politics.

This is exacerbated by the fact that at the Pedicle's toe tip, where the Luapula River ostensibly flows out of the Bangweulu system, the river swamps are at least 6 kilometres (3.7 mi) wide and the floodplain is 60 kilometres (37 mi) wide,[4] making a road impossible with the resources available for most of the 20th century.

The most southerly road possible into Luapula keeping to Zambian territory was pushed, by these circumstances, another 200 kilometres (120 mi) north, going around Lake Bangweulu.

As well as affecting communication for about one-quarter of the country with the centre and west, it potentially exposes a greater part of Zambia, which has generally enjoyed peace for more than 100 years, to conflict in Katanga, which has not.