Congreve rocket

Lieutenant general Thomas Desaguliers, colonel commandant of the Royal Artillery at Woolwich, was impressed by reports of their effectiveness, and undertook several unsuccessful experiments to produce his own rocket weapons.

The king of Mysore, Tipu Sultan and his father Hyder Ali[6] developed the military tactic of using massed wave attacks supported by rocket artillery against enemy positions.

In 1792, Tipu Sultan wrote a military manual called Fathul Mujahidin, in which two hundred artillerymen specialising in rocket artillery were prescribed to each Mysorean brigade (known as cushoons).

[citation needed] At the Battle of Pollilur (1780) during the Second Anglo-Mysore War, Colonel William Baillie's ammunition stores are thought to have been detonated by a hit from one of Tipu Sultan's Mysorean rockets, which contributed to the British defeat.

Quoting Forrest:"At this point (near the village of Sultanpet, Figure 5) there was a large tope, or grove, which gave shelter to Tipu's rocketmen and had obviously to be cleaned out before the siege could be pressed closer to Srirangapattanam Island.

The commander chosen for this operation was Col. Wellesley, but advancing towards the tope after dark on 5 April 1799, he was set upon with rockets and musket-fires, lost his way and, as Beatson politely puts it, had to "postpone the attack" until a more favourable opportunity should offer.

Every illumination of blue lights was accompanied by a shower of rockets, some of which entered the head of the column, passing through to the rear, causing death, wounds, and dreadful lacerations from the long bamboos of twenty or thirty feet, which are invariably attached to them'.

Rocket sizes were designated by the calibre of the tube, using the then-standard British method of using weight in pounds as a measure of cannon bore.

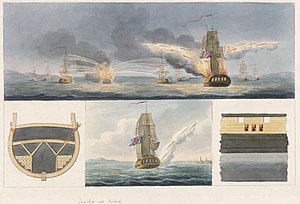

The lack of specific accuracy with the larger rockets at long range was not a problem if the purpose was to set fire to a town or a number of moored ships; this was shown with the attack on the French Fleet in Aix and Basque roads and at the bombardment of Copenhagen.

The order to fire is given – port-fire applied – the fidgety missile begins to sputter out sparks and wriggle its tail for a second or so, and then darts forth straight up the chaussée.

In April 1806, Rear Admiral Sidney Smith took rockets on a little-known mission to the Mediterranean to aid Sicily and the Kingdom of Naples in their struggle against the French.

In 1807, Copenhagen was bombarded by more than 14,000 missiles in the form of metal balls, explosive and incendiary bombs from cannons and mortars, and about 300 Congreve rockets.

Congreve accompanied Lord Cochrane in the fire-ship, rocket, and shell attack on the French Fleet in Aix and Basque roads on 11 April 1809.

This rocket ship was deployed at the naval bombardment of Flushing, where they wrought such havoc that ‘General Monnet, the French commandant, made a formal protest to Lord Chatham’ against their use.

In May 1813, a detachment which had been training with rockets at Woolwich under Second Captain Richard Bogue RHA was inspected by a committee of Royal Artillery officers who recommended that it be tried in combat.

[15] Captain Bogue was however killed by a sharpshooter in the subsequent cavalry charge, and the village of Paunsdorf was eventually retaken by the French Imperial Guard.

[23][24][25] A third battalion of Royal Marines arrived in North America in 1814, with an attached rocket detachment commanded by Lieutenant John Lawrence, which subsequently participated in the Chesapeake campaign.

Rockets fired by a detachment of the Royal Marine Artillery, though inaccurate, unnerved the attacking American forces, and contributed to the defense of the blockhouse and mill.

An American force, sent to destroy General Gordon Drummond's source of flour, was challenged by a contingent of infantry which was supported by a light field cannon and a frame of Congreve rockets.

Things reached a head after a particular atrocity; following the U.S success in the Second Barbary War, Britain decided to stamp out their activities, and the Netherlands agreed to assist.

"It was by their fire that all the ships in the port, with the exception of the outer frigate, were in flames which extended rapidly over the whole arsenal, storehouses and gun boats, exhibiting a spectacle of awful grandeur".

[32] Subsequent reports made clear that the rockets were fired from about 40 yards and were highly effective in killing whales that had already been conventionally harpooned.

Early on that morning a whale, of the largest size, was discovered near the ship; I immediately pursued it, and when sufficiently near, fired a rocket into its side; the effect it had on the fish was tremendous – every joint in its body shook, and, after lying for a few seconds in this agitated way, it turned on its back and died.

My next attempt was on the 9th July, on a whale of the same size as the former, but owing to the rapid motion of the fish, and a heavy swell of the sea, which rendered the boat unsteady, the rocket entered below the middle part of the body, in consequence of which its effect was considerably lessened, its frame, however, was much shook by the explosion, and it immediately sunk, but rose again, blowing an immense quantity of blood: it was then struck with a harpoon, and killed with lances.

Having witnessed the effects of incendiary rockets on grain warehouses of Danzig in 1813, artillery captain Józef Bem of the Kingdom of Poland started his own experiments with what was then called in Polish raca kongrewska.

These culminated in his 1819 report Notes sur les fusées incendiaires (German edition: Erfahrungen über die Congrevischen Brand-Raketen bis zum Jahre 1819 in der Königlichen Polnischen Artillerie gesammelt, Weimar, 1820).

The research took place in the Warsaw Arsenal, where captain Józef Kosiński also developed the multiple-rocket launchers adapted from horse artillery gun carriage.

[45] At the Battle of Ruapekapeka, December 1845–January 1846, Egerton's rocket brigade, located at the British main camp, operated two of HMS North Star's rocket-tubes—24-pounder and 12-pounder.

The Brazilian Navy employed them during the Battle of Curupayti (22 September 1866), trying to destroy the reinforced Paraguayan trench field, but the rockets fell short.

[55] A wide variety of Congreve rockets were displayed at Firepower - The Royal Artillery Museum[56] in South-East London, ranging in size from 3 to 300 pounds (1.4 to 136.1 kg).