Rocket

[3] Significant scientific, interplanetary and industrial use did not occur until the 20th century, when rocketry was the enabling technology for the Space Age, including setting foot on the Moon.

Rockets are now used for fireworks, missiles and other weaponry, ejection seats, launch vehicles for artificial satellites, human spaceflight, and space exploration.

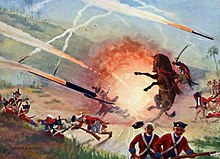

Internal-combustion rocket propulsion is mentioned in a reference to 1264, recording that the "ground-rat", a type of firework, had frightened the Empress-Mother Gongsheng at a feast held in her honor by her son the Emperor Lizong.

[5] Subsequently, rockets are included in the military treatise Huolongjing, also known as the Fire Drake Manual, written by the Chinese artillery officer Jiao Yu in the mid-14th century.

This text mentions the first known multistage rocket, the 'fire-dragon issuing from the water' (Huo long chu shui), thought to have been used by the Chinese navy.

Between 1270 and 1280, Hasan al-Rammah wrote al-furusiyyah wa al-manasib al-harbiyya (The Book of Military Horsemanship and Ingenious War Devices), which included 107 gunpowder recipes, 22 of them for rockets.

[1] Artis Magnae Artilleriae pars prima, an important early modern work on rocket artillery, by Casimir Siemienowicz, was first printed in Amsterdam in 1650.

In 1920, Professor Robert Goddard of Clark University published proposed improvements to rocket technology in A Method of Reaching Extreme Altitudes.

The Americans captured a large number of German rocket scientists, including Wernher von Braun, in 1945, and brought them to the United States as part of Operation Paperclip.

After World War II scientists used rockets to study high-altitude conditions, by radio telemetry of temperature and pressure of the atmosphere, detection of cosmic rays, and further techniques; note too the Bell X-1, the first crewed vehicle to break the sound barrier (1947).

The acceleration of these gases through the engine exerts force ("thrust") on the combustion chamber and nozzle, propelling the vehicle (according to Newton's Third Law).

Sometimes the propellant is not burned but still undergoes a chemical reaction, and can be a 'monopropellant' such as hydrazine, nitrous oxide or hydrogen peroxide that can be catalytically decomposed to hot gas.

The outstanding vehicle, 6L, had dummy upper stages and therefore no escape system giving the N1 booster a 100% success rate for egress from a failed launch.

According to the United States National Association of Rocketry (nar) Safety Code,[54] model rockets are constructed of paper, wood, plastic and other lightweight materials.

Despite its inherent association with extremely flammable substances and objects with a pointed tip traveling at high speeds, model rocketry historically has proven[55][56] to be a very safe hobby and has been credited as a significant source of inspiration for children who eventually become scientists and engineers.

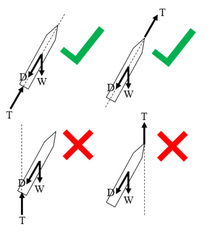

Orbital launch vehicles commonly take off vertically, and then begin to progressively lean over, usually following a gravity turn trajectory.

Doglegs are undesirable due to extra onboard fuel required, causing heavier load, and a reduction of vehicle performance.

[67] To combat this, NASA developed a sound suppression system which can flow water at rates up to 900,000 gallons per minute (57 m3/s) onto the launch pad.

[68] Without the sound suppression system, acoustic waves would reflect off of the launch pad towards the rocket, vibrating the sensitive payload and crew.

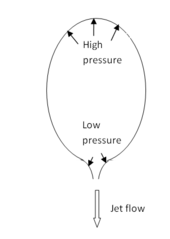

The higher the speed of the gases, the lower the pressure of the gas (Bernoulli's principle or conservation of energy) acting on that part of the combustion chamber.

The rate of propellant flow through a rocket engine is often deliberately varied over a flight, to provide a way to control the thrust and thus the airspeed of the vehicle.

In practice the effective exhaust velocities of rockets varies but can be extremely high, ~4500 m/s, about 15 times the sea level speed of sound in air.

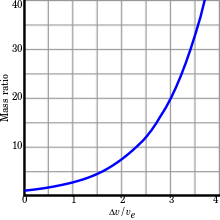

For example, the Soyuz escape system can produce 20 g.[47] Achievable mass ratios are highly dependent on many factors such as propellant type, the design of engine the vehicle uses, structural safety margins and construction techniques.

The highest mass ratios are generally achieved with liquid rockets, and these types are usually used for orbital launch vehicles, a situation which calls for a high delta-v.

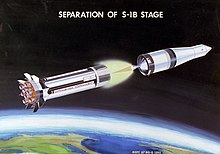

Some notable mass fractions are found in the following table (some aircraft are included for comparison purposes): Thus far, the required velocity (delta-v) to achieve orbit has been unattained by any single rocket because the propellant, tankage, structure, guidance, valves and engines and so on, take a particular minimum percentage of take-off mass that is too great for the propellant it carries to achieve that delta-v carrying reasonable payloads.

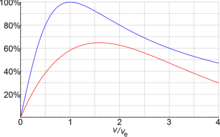

The energy density of a typical rocket propellant is often around one-third that of conventional hydrocarbon fuels; the bulk of the mass is (often relatively inexpensive) oxidizer.

Since the energy ultimately comes from fuel, these considerations mean that rockets are mainly useful when a very high speed is required, such as ICBMs or orbital launch.

[94] In May 2003 the astronaut office made clear its position on the need and feasibility of improving crew safety for future NASA crewed missions indicating their "consensus that an order of magnitude reduction in the risk of human life during ascent, compared to the Space Shuttle, is both achievable with current technology and consistent with NASA's focus on steadily improving rocket reliability".

Extreme performance requirements for rockets reaching orbit correlate with high cost, including intensive quality control to ensure reliability despite the limited safety factors allowable for weight reasons.

[102] Components produced in small numbers if not individually machined can prevent amortization of R&D and facility costs over mass production to the degree seen in more pedestrian manufacturing.

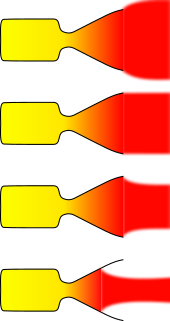

- Underexpanded

- Ideally expanded

- Overexpanded

- Grossly overexpanded