Prototype theory

It emerged in 1971 with the work of psychologist Eleanor Rosch, and it has been described as a "Copernican Revolution" in the theory of categorization for its departure from the traditional Aristotelian categories.

[1] It has been criticized by those that still endorse the traditional theory of categories, like linguist Eugenio Coseriu and other proponents of the structural semantics paradigm.

Prototype theory has also been applied in linguistics, as part of the mapping from phonological structure to semantics.

Importantly, Hampton's prototype model explains the vagueness that can occur at the boundary of conceptual categories.

Basic categories are relatively homogeneous in terms of sensory-motor affordances — a chair is associated with bending of one's knees, a fruit with picking it up and putting it in your mouth, etc.

On the other hand, basic categories in [animal], i.e. [dog], [bird], [fish], are full of informational content and can easily be categorized in terms of Gestalt and semantic features.

Clearly semantic models based on attribute-value pairs fail to identify privileged levels in the hierarchy.

Linguistically, types of bird (swallow, robin, gull) are basic level - they have mono-morphemic nouns, which fall under the superordinate BIRD, and have subordinates expressed by noun phrases (herring gull, male robin).

Verbs, for example, seem to defy a clear prototype: [to run] is hard to split up in more or less central members.

In her 1975 paper, Rosch asked 200 American college students to rate, on a scale of 1 to 7, whether they regarded certain items as good examples of the category furniture.

Further evidence that some members of a category are more privileged than others came from experiments involving: Subsequent to Rosch's work, prototype effects have been investigated widely in areas such as colour cognition,[11] and also for more abstract notions: subjects may be asked, e.g. "to what degree is this narrative an instance of telling a lie?".

[12] Similar work has been done on actions (verbs like look, kill, speak, walk [Pulman:83]), adjectives like "tall",[13] etc.

Another aspect in which Prototype Theory departs from traditional Aristotelian categorization is that there do not appear to be natural kind categories (bird, dog) vs. artifacts (toys, vehicles).

Medin, Altom, and Murphy found that using a mixture of prototype and exemplar information, participants were more accurately able to judge categories.

This influential theory has resulted in a view of semantic components more as possible rather than necessary contributors to the meaning of texts.

Therefore, there is a distance between focal, or prototypical members of the category, and those that continue outwards from them, linked by shared features.

[17] Within language we find instances of combined categories, such as tall man or small elephant.

Mikulincer, Mario & Paz, Dov & Kedem, Perry focused on the dynamic nature of prototypes and how represented semantic categories actually changes due to emotional states.

[1] Douglas L. Medin and Marguerite M. Schaffer showed by experiment that a context theory of classification which derives concepts purely from exemplars (cf.

[18] Linguists, including Stephen Laurence writing with Eric Margolis, have suggested problems with the prototype theory.

Laurence and Margolis concluded that "prototype structure has no implication for whether subjects represent a category as being graded" (p. 33).

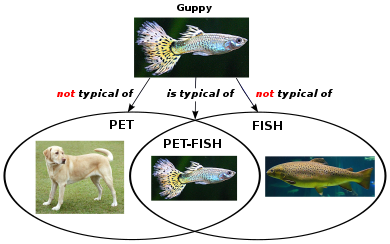

[19] Daniel Osherson and Edward Smith raised the issue of pet fish for which the prototype might be a guppy kept in a bowl in someone's house.

Antonio Lieto and Gian Luca Pozzato have proposed a typicality-based compositional logic (TCL) that is able to account for both complex human-like concept combinations (like the PET-FISH problem) and conceptual blending.