Jerry Fodor

Jerry Alan Fodor (/ˈfoʊdər/ FOH-dər; April 22, 1935 – November 29, 2017) was an American philosopher and the author of works in the fields of philosophy of mind and cognitive science.

He received his degree (summa cum laude) from Columbia University in 1956, where he wrote a senior thesis on Søren Kierkegaard.

[4][5] Besides his interest in philosophy, Fodor followed opera and regularly wrote columns for the London Review of Books on that and other topics.

Fodor adhered to a species of functionalism, maintaining that thinking and other mental processes consist primarily of computations operating on the syntax of the representations that make up the language of thought.

[8][9] For Fodor, significant parts of the mind, such as perceptual and linguistic processes, are structured in terms of modules, or "organs", which he defines by their causal and functional roles.

His contributions in this area include the so-called asymmetric causal theory of reference and his many arguments against semantic holism.

He argued that mental states are multiple realizable and that there is a hierarchy of explanatory levels in science such that the generalizations and laws of a higher-level theory of psychology or linguistics, for example, cannot be captured by the low-level explanations of the behavior of neurons and synapses.

[17] Fodor's own position, instead, is that to properly account for the nature of intentional attitudes, it is necessary to employ a three-place relation between individuals, representations and propositional contents.

[18][13] Considering mental states as three-place relations in this way, representative realism makes it possible to hold together all of the elements necessary to the solution of this problem.

[19][13] Following in the path paved by linguist Noam Chomsky, Fodor developed a strong commitment to the idea of psychological nativism.

[26] Two properties of modularity, informational encapsulation and domain specificity, make it possible to relate functional architecture to mental content.

A person's ability to elaborate information independently from their background beliefs allows Fodor to give an atomistic and causal account of mental content.

[27][28][29] Fodor complained that Pinker, Plotkin and other members of what he sarcastically called "the New Synthesis" had taken modularity and similar ideas way too far.

[32] Dennett maintains that it is possible to be realist with regard to intentional states without having to commit oneself to the reality of mental representations.

Fodor draws on the work of Noam Chomsky to both model his theory of the mind and to refute alternative architectures such as connectionism.

[39][13] For Fodor, this formal notion of thought processes also has the advantage of highlighting the parallels between the causal role of symbols and the contents which they express.

Fodor went on to criticize inferential role semantics (IRS) because its commitment to an extreme form of holism excludes the possibility of a true naturalization of the mental.

[41]Having criticized the idea that semantic evaluation concerns only the internal relations between the units of a symbolic system, Fodor can adopt an externalist position with respect to mental content and meaning.

The type-identity theory, on the other hand, failed to explain the fact that radically different physical systems can find themselves in the identical mental state.

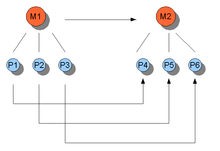

Under this view, for example, I and a computer can both instantiate ("realize") the same functional state though we are made of completely different material stuff (see graphic at right).

[45] In the same, the authors argue that much neo-Darwinian literature is "distressingly uncritical" and that Charles Darwin's theory of evolution "overestimates the contribution the environment makes in shaping the phenotype of a species and correspondingly underestimates the effects of endogenous variables".

[46] Evolutionary biologist Jerry Coyne describes this book as "a profoundly misguided critique of natural selection"[47] and "as biologically uninformed as it is strident".

[48] Moral philosopher and anti-scientism author Mary Midgley praises What Darwin Got Wrong as "an overdue and valuable onslaught on neo-Darwinist simplicities".

[52][53] In 1996–1997, Fodor delivered the John Locke Lectures at the University of Oxford, titled Concepts: Where Cognitive Science Went Wrong, which went on to become a 1998 book.

[60][61][62] Simon Blackburn in Spreading the Word (1984) has accused the language of thought hypothesis of falling prey to an infinite regress.

The same is obviously true, suggests Dennett, of many of our everyday automatic behaviors such as "desiring to breathe clear air" in a stuffy environment.

[61] Linguists and philosophers of language such as Kent Bach have criticized Fodor's self-proclaimed "extreme" concept nativism.

[62] Whether or not the differing interpretations of "fast" in these sentences are specified in the semantics of English, or are the result of pragmatic inference, is a matter of debate.

"[67] Some critics find it difficult to accept Fodor's insistence that a large, perhaps implausible, number of concepts are primitive and undefinable.

[62] In her 1999 book What's Within, Fiona Cowie argued against Fodor's innatist view, preferring a John Locke-style empiricism.