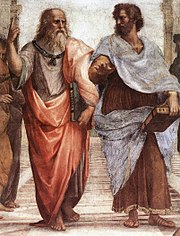

Theory of forms

According to this theory, Forms—conventionally capitalized and also commonly translated as "Ideas"[4]—are the non-physical, timeless, absolute, and unchangeable essences of all things, which objects and matter in the physical world merely imitate, resemble, or participate in.

[5] Plato speaks of these entities only through the characters (primarily Socrates) in his dialogues who sometimes suggest that these Forms are the only objects of study that can provide knowledge.

[6] Scriptures written by Pythagoras suggest that he developed a similar theory earlier than Plato, though Pythagoras's theory was narrower, proposing that the non-physical and timeless essences that compose the physical world are, in fact, numbers.

The early Greek concept of form precedes attested philosophical usage, and is represented by a number of words which mainly relate to vision, sight, and appearance.

The theory itself is contested by characters within Plato's dialogues, and it remains a general point of controversy in philosophy.

[7] The original meaning of the term εἶδος (eîdos), "visible form", and related terms μορφή (morphḗ), "shape",[8] and φαινόμενα (phainómena), "appearances", from φαίνω (phaínō), "shine", Indo-European *bʰeh₂- or *bhā-[9] remained stable over the centuries until the beginning of Western philosophy, when they became equivocal, acquiring additional specialized philosophic meanings.

The perfect circle, partly represented by a curved line, and a precise definition, cannot be drawn.

Plato often invokes, particularly in his dialogues Phaedo, Republic and Phaedrus, poetic language to illustrate the mode in which the Forms are said to exist.

Near the end of the Phaedo, for example, Plato describes the world of Forms as a pristine region of the physical universe located above the surface of the Earth (Phd.

247c ff); and in the Republic the sensible world is contrasted with the intelligible realm (noēton topon) in the famous Allegory of the Cave.

It would be a mistake to take Plato's imagery as positing the intelligible world as a literal physical space apart from this one.

Forms are first introduced in the Phaedo, but in that dialogue the concept is simply referred to as something the participants are already familiar with, and the theory itself is not developed.

Commentators have been left with the task of explaining what Forms are and how visible objects participate in them, and there has been no shortage of disagreement.

Some scholars advance the view that Forms are paradigms, perfect examples on which the imperfect world is modeled.

Yet others interpret Forms as "stuffs," the conglomeration of all instances of a quality in the visible world.

Plato uses the tool-maker's blueprint as evidence that Forms are real:[26]... when a man has discovered the instrument which is naturally adapted to each work, he must express this natural form, and not others which he fancies, in the material ....Perceived circles or lines are not exactly circular or straight, and true circles and lines could never be detected since by definition they are sets of infinitely small points.

The young Socrates did not give up the Theory of Forms over the Third Man but took another tack, that the particulars do not exist as such.

[30] The topic of Aristotle's criticism of Plato's Theory of Forms is a large one and continues to expand.

[31] As a historian of prior thought, Aristotle was invaluable, however this was secondary to his own dialectic and in some cases he treats purported implications as if Plato had actually mentioned them, or even defended them.

Uncharitably, this leads him to something like a contradiction: Forms existing as the objects of science, but not-existing as substance.

By one way in which he unpacks the concept, the Forms would cease to be of one essence due to any multiple participation.

Plato had postulated that we know Forms through a remembrance of the soul's past lives and Aristotle's arguments against this treatment of epistemology are compelling.

Scholasticism was a highly multinational, polyglottal school of philosophy, and the nominalist argument may be more obvious if an example is given in more than one language.

The English "pencil" originally meant "small paintbrush"; the term later included the silver rod used for silverpoint.

The German "Bleistift" and "Silberstift" can both be called "Stift", but this term also includes felt-tip pens, which are clearly not pencils.

The shifting and overlapping nature of these concepts makes it easy to imagine them as mere names, with meanings not rigidly defined, but specific enough to be useful for communication.