Copernican heliocentrism

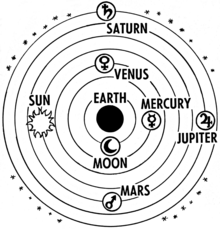

This model positioned the Sun at the center of the Universe, motionless, with Earth and the other planets orbiting around it in circular paths, modified by epicycles, and at uniform speeds.

Copernicus's challenge was to present a practical alternative to the Ptolemaic model by more elegantly and accurately determining the length of a solar year while preserving the metaphysical implications of a mathematically ordered cosmos.

Thus, his heliocentric model retained several of the Ptolemaic elements, causing inaccuracies, such as the planets' circular orbits, epicycles, and uniform speeds,[1] while at the same time using ideas such as: Philolaus (4th century BCE) was one of the first to hypothesize movement of the Earth, probably inspired by Pythagoras' theories about a spherical, moving globe.

In the 3rd century BCE, Aristarchus of Samos proposed what was, so far as is known, the first serious model of a heliocentric Solar System, having developed some of Heraclides Ponticus' theories (speaking of a "revolution of the Earth on its axis" every 24 hours).

Though his original text has been lost, a reference in Archimedes' book The Sand Reckoner (Archimedis Syracusani Arenarius & Dimensio Circuli) describes a work in which Aristarchus advanced the heliocentric model.

But Aristarchus has brought out a book consisting of certain hypotheses, wherein it appears, as a consequence of the assumptions made, that the universe is many times greater than the 'universe' just mentioned.

Throughout the Middle Ages it was spoken of as the authoritative text on astronomy, although its author remained a little understood figure frequently mistaken as one of the Ptolemaic rulers of Egypt.

[8] In 499 CE, the Indian astronomer and mathematician Aryabhata, influenced by Greek astronomy,[9] propounded a planetary model that explicitly incorporated Earth's rotation about its axis, which he explains as the cause of what appears to be an apparent westward motion of the stars.

[24] Otto E. Neugebauer in 1957 argued that the debate in 15th-century Latin scholarship must also have been informed by the criticism of Ptolemy produced after Averroes, by the Ilkhanid-era (13th to 14th centuries) Persian school of astronomy associated with the Maragheh observatory (especially the works of al-Urdi, al-Tusi and al-Shatir).

The state of the question as received by Copernicus is summarized in the Theoricae novae planetarum by Peuerbach, compiled from lecture notes by Regiomontanus in 1454, but not printed until 1472.

[29] The state of knowledge on planetary theory received by Copernicus is summarized in Peuerbach's Theoricae Novae Planetarum (printed in 1472 by Regiomontanus).

[33] The major features of Copernican theory are: Inspiration came to Copernicus not from observation of the planets, but from reading two authors, Cicero and Plutarch[citation needed].

[38] However, no likely candidate for this conjectured work has come to light, and other scholars have argued that Copernicus could well have developed these ideas independently of the late Islamic tradition.

[39] Nevertheless, Copernicus cited some of the Islamic astronomers whose theories and observations he used in De Revolutionibus, namely al-Battani, Thabit ibn Qurra, al-Zarqali, Averroes, and al-Bitruji.

[40] It has been suggested[41][42] that the idea of the Tusi couple may have arrived in Europe leaving few manuscript traces, since it could have occurred without the translation of any Arabic text into Latin.

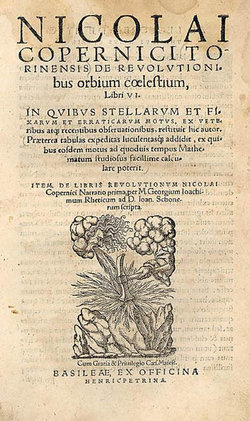

Since Copernicus' hypothesis was believed to contradict the Old Testament account of the Sun's movement around the Earth (Joshua 10:12-13), this was apparently written to soften any religious backlash against the book.

[45] Then, in a lengthy introduction, Copernicus dedicated the book to Pope Paul III, explaining his ostensible motive in writing the book as relating to the inability of earlier astronomers to agree on an adequate theory of the planets, and noting that if his system increased the accuracy of astronomical predictions it would allow the Church to develop a more accurate calendar.

Even forty-five years after the publication of De Revolutionibus, the astronomer Tycho Brahe went so far as to construct a cosmology precisely equivalent to that of Copernicus, but with the Earth held fixed in the center of the celestial sphere instead of the Sun.

For his contemporaries, the ideas presented by Copernicus were not markedly easier to use than the geocentric theory and did not produce more accurate predictions of planetary positions.

Tycho, arguably the most accomplished astronomer of his time, appreciated the elegance of the Copernican system, but objected to the idea of a moving Earth on the basis of physics, astronomy, and religion.

The Copernican Revolution, a paradigm shift from the Ptolemaic model of the heavens, which described the cosmos as having Earth as a stationary body at the center of the universe, to the heliocentric model with the Sun at the center of the Solar System, spanned over a century, beginning with the publication of Copernicus' De revolutionibus orbium coelestium and ending with the work of Isaac Newton.

[50] During the 17th century, several further discoveries eventually led to the wider acceptance of heliocentrism: From a modern point of view, the Copernican model has a number of advantages.

In his book The Sleepwalkers: A History of Man's Changing Vision of the Universe (1959), Arthur Koestler attempted to deconstruct the Copernican "revolution" by portraying Copernicus as a coward who was reluctant to publish his work due to a crippling fear of ridicule.