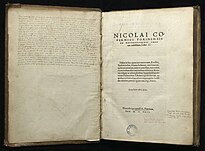

De revolutionibus orbium coelestium

De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (English translation: On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres) is the seminal work on the heliocentric theory of the astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus (1473–1543) of the Polish Renaissance.

The book, first printed in 1543 in Nuremberg, Holy Roman Empire, offered an alternative model of the universe to Ptolemy's geocentric system, which had been widely accepted since ancient times.

Copernicus initially outlined his system in a short, untitled, anonymous manuscript that he distributed to several friends, referred to as the Commentariolus.

A physician's library list dating to 1514 includes a manuscript whose description matches the Commentariolus, so Copernicus must have begun work on his new system by that time.

[citation needed] Copernicus' values differed slightly from the ones published by Schöner in 1544 in Observationes XXX annorum a I. Regiomontano et B. Walthero Norimbergae habitae, [4°, Norimb.

Close examination of the manuscript, including the different types of paper used, helped scholars construct an approximate timetable for its composition.

Due to its friendly reception, Copernicus finally agreed to publication of more of his main work—in 1542, a treatise on trigonometry, which was taken from the second book of the still unpublished De revolutionibus.

From the first edition, Copernicus' book was prefixed with an anonymous preface which argues that the following is a calculus consistent with the observations, and cannot resolve philosophical truths.

De revolutionibus is divided into six "books" (sections or parts), following closely the layout of Ptolemy's Almagest which it updated and replaced:[6] Copernicus argued that the universe comprised eight spheres.

Despite Copernicus' adherence to this aspect of ancient astronomy, his radical shift from a geocentric to a heliocentric cosmology was a serious blow to Aristotle's science—and helped usher in the Scientific Revolution.

Osiander's letter stated that Copernicus' system was mathematics intended to aid computation and not an attempt to declare literal truth: it is the duty of an astronomer to compose the history of the celestial motions through careful and expert study.

On the contrary, if they provide a calculus consistent with the observations, that alone is enough ... For this art, it is quite clear, is completely and absolutely ignorant of the causes of the apparent [movement of the heavens].

But neither of them will understand or state anything certain, unless it has been divinely revealed to him ... Let no one expect anything certain from astronomy, which cannot furnish it, lest he accept as the truth ideas conceived for another purpose, and depart this study a greater fool than when he entered.

[9] Osiander's interest in astronomy was theological, hoping for "improving the chronology of historical events and thus providing more accurate apocalyptic interpretations of the Bible... [he shared in] the general awareness that the calendar was not in agreement with astronomical movement and therefore, needed to be corrected by devising better models on which to base calculations."

[9] Ptolemy's theory contained a hypothesis about the epicycle of Venus that was viewed as absurd if seen as anything other than a geometrical device (its brightness and distance should have varied greatly, but they don't).

"[9] Writing Ad lectorem, Osiander was influenced by Pico della Mirandola's idea that humanity "orders [an intellectual] cosmos out of the chaos of opinions.

Rather than having Pico's focus on human effort, Osiander followed Cusa's idea that understanding the Universe and its Creator only came from divine inspiration rather than intellectual organization.

As historian Robert S. Westman puts it, "The more profound source of Rheticus's ire however, was Osiander's view of astronomy as a disciple fundamentally incapable of knowing anything with certainty.

While Pico could bring into concordance writers like Aristotle, Plato, Plotinus, Averroes, Avicenna, and Aquinas, the lack of consensus he saw in astronomy was a proof to him of its fallibility alongside astrology.

Thus the conflict between Piconian skepticism and secure principles for the science of the stars was built right into the complex dedicatory apparatus of De Revolutionibus itself.

Rheticus...suspected Osiander had prefaced the work; if he knew this for certain, he declared, he would rough up the fellow so violently that in future he would mind his own business.

In one of his Tischreden (Table Talks), Martin Luther is quoted as saying in 1539: People gave ear to an upstart astrologer who strove to show that the earth revolves, not the heavens or the firmament, the sun and the moon ...

[19] Copernicus had made the book extremely technical, unreadable to all but the most advanced astronomers of the day, allowing it to disseminate into their ranks before stirring great controversy.

[20] And, like Osiander, contemporary mathematicians and astronomers encouraged its audience to view it as a useful mathematical model without necessarily being true about causes, thereby somewhat shielding it from accusations of blasphemy.

In England, Robert Recorde, John Dee, Thomas Digges and William Gilbert were among those who adopted his position; in Germany, Christian Wurstisen, Christoph Rothmann and Michael Mästlin, the teacher of Johannes Kepler; in Italy, Giambattista Benedetti and Giordano Bruno whilst Franciscus Patricius accepted the rotation of the Earth.

In 1549, Melanchthon, Luther's principal lieutenant, wrote against Copernicus, pointing to the theory's apparent conflict with Scripture and advocating that "severe measures" be taken to restrain the impiety of Copernicans.

[26] The works of Copernicus and Zúñiga—the latter for asserting that De revolutionibus was compatible with Catholic faith—were placed on the Index of Forbidden Books by a decree of the Sacred Congregation[which?]

[30] Owen Gingerich, an eminent astronomer and historian of science who has written on both Nicolaus Copernicus and Johannes Kepler, disproved this after a 35-year project to examine every surviving copy of the first two editions.

Due largely to Gingerich's scholarship, De revolutionibus has been researched and catalogued better than any other first-edition historic text except for the original Gutenberg Bible.