Scientific Revolution

[8] The era of the Scientific Renaissance focused to some degree on recovering the knowledge of the ancients and is considered to have culminated in Isaac Newton's 1687 publication Principia which formulated the laws of motion and universal gravitation,[9] thereby completing the synthesis of a new cosmology.

The subsequent Age of Enlightenment saw the concept of a scientific revolution emerge in the 18th-century work of Jean Sylvain Bailly, who described a two-stage process of sweeping away the old and establishing the new.

"Among the most conspicuous of the revolutions which opinions on this subject have undergone, is the transition from an implicit trust in the internal powers of man's mind to a professed dependence upon external observation; and from an unbounded reverence for the wisdom of the past, to a fervid expectation of change and improvement.

[20] Although printers' blunders still often resulted in the spread of false data (for instance, in Galileo's Sidereus Nuncius (The Starry Messenger), published in Venice in 1610, his telescopic images of the lunar surface mistakenly appeared back to front), the development of engraved metal plates allowed accurate visual information to be made permanent, a change from previously, when woodcut illustrations deteriorated through repetitive use.

In 1611 English poet John Donne wrote: [The] new Philosophy calls all in doubt, The Element of fire is quite put out; The Sun is lost, and th'earth, and no man's wit

[22]Butterfield was less disconcerted but nevertheless saw the change as fundamental: Since that revolution turned the authority in English not only of the Middle Ages but of the ancient world—since it started not only in the eclipse of scholastic philosophy but in the destruction of Aristotelian physics—it outshines everything since the rise of Christianity and reduces the Renaissance and Reformation to the rank of mere episodes, mere internal displacements within the system of medieval Christendom.... [It] looms so large as the real origin both of the modern world and of the modern mentality that our customary periodization of European history has become an anachronism and an encumbrance.

Yet, many of the leading figures in the scientific revolution imagined themselves to be champions of a science that was more compatible with Christianity than the medieval ideas about the natural world that they replaced.

[5] The ideas that remained, which were transformed fundamentally during the Scientific Revolution, include: Ancient precedent existed for alternative theories and developments which prefigured later discoveries in the area of physics and mechanics; but in light of the limited number of works to survive translation in a period when many books were lost to warfare, such developments remained obscure for centuries and are traditionally held to have had little effect on the re-discovery of such phenomena; whereas the invention of the printing press made the wide dissemination of such incremental advances of knowledge commonplace.

Thomas Hobbes, George Berkeley, and David Hume were the philosophy's primary exponents who developed a sophisticated empirical tradition as the basis of human knowledge.

His demand for a planned procedure of investigating all things natural marked a new turn in the rhetorical and theoretical framework for science, much of which still surrounds conceptions of proper methodology today.

[43] For this purpose of obtaining knowledge of and power over nature, Bacon outlined in this work a new system of logic he believed to be superior to the old ways of syllogism, developing his scientific method, consisting of procedures for isolating the formal cause of a phenomenon (heat, for example) through eliminative induction.

It is written in the language of mathematics, and its characters are triangles, circles, and other geometrical figures, without which it is humanly impossible to understand a single word of it; without these, one is wandering around in a dark labyrinth.

According to Thomas Kuhn, Newton and Descartes held the teleological principle that God conserved the amount of motion in the universe: Gravity, interpreted as an innate attraction between every pair of particles of matter, was an occult quality in the same sense as the scholastics' "tendency to fall" had been.... By the mid eighteenth century that interpretation had been almost universally accepted, and the result was a genuine reversion (which is not the same as a retrogression) to a scholastic standard.

By deriving Kepler's laws of planetary motion from his mathematical description of gravity, and then using the same principles to account for the trajectories of comets, the tides, the precession of the equinoxes, and other phenomena, Newton removed the last doubts about the validity of the heliocentric model of the cosmos.

[83] After the exchanges with Hooke, Newton worked out proof that the elliptical form of planetary orbits would result from a centripetal force inversely proportional to the square of the radius vector.

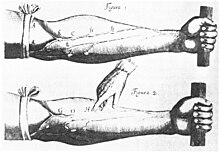

It emphasized the priority of dissection and what has come to be called the "anatomical" view of the body, seeing human internal functioning as an essentially corporeal structure filled with organs arranged in three-dimensional space.

[90] Niccolò Massa was an Italian anatomist who wrote an early anatomy text Anatomiae Libri Introductorius in 1536, described the cerebrospinal fluid and was the author of several medical works.

Surgeon Ambroise Paré was a leader in surgical techniques and battlefield medicine, especially the treatment of wounds,[93] and Herman Boerhaave is sometimes referred to as a "father of physiology" because of his exemplary teaching in Leiden and his textbook Institutiones medicae (1708).

[95] Practical attempts to improve the refining of ores and their extraction to smelt metals were an important source of information for early chemists in the 16th century, among them Georgius Agricola, who published his great work De re metallica in 1556.

In it, he describes the inverse-square law governing the intensity of light, reflection by flat and curved mirrors, and principles of pinhole cameras, as well as the astronomical implications of optics such as parallax and the apparent sizes of heavenly bodies.

These included the Opera reliqua (also known as Christiani Hugenii Zuilichemii, dum viveret Zelhemii toparchae, opuscula posthuma) and the Traité de la lumière.

"[103] Antonie van Leeuwenhoek constructed powerful single lens microscopes and made extensive observations that he published around 1660, paving the way for the science of microbiology.

He noticed that dry weather with north or east wind was the most favourable atmospheric condition for exhibiting electric phenomena—an observation liable to misconception until the difference between conductor and insulator was understood.

[143] The increase in uses for such instruments, and their widespread use in global exploration and conflict, created a need for new methods of manufacture and repair, which would be met by the Industrial Revolution.

[146] A weakness of the idea of a scientific revolution is the lack of a systematic approach to the question of knowledge in the period comprehended between the 14th and 17th centuries,[147] leading to misunderstandings on the value and role of modern authors.

From this standpoint, the continuity thesis is the hypothesis that there was no radical discontinuity between the intellectual development of the Middle Ages and the developments in the Renaissance and early modern period and has been deeply and widely documented by the works of scholars like Pierre Duhem, John Hermann Randall, Alistair Crombie and William A. Wallace, who proved the preexistence of a wide range of ideas used by the followers of the Scientific Revolution thesis to substantiate their claims.

Bala proposes that the changes involved in the Scientific Revolution—the mathematical realist turn, the mechanical philosophy, the atomism, the central role assigned to the Sun in Copernican heliocentrism—have to be seen as rooted in multicultural influences on Europe.

He sees specific influences in Alhazen's physical optical theory, Chinese mechanical technologies leading to the perception of the world as a machine, the Hindu–Arabic numeral system, which carried implicitly a new mode of mathematical atomic thinking, and the heliocentrism rooted in ancient Egyptian religious ideas associated with Hermeticism.

[155] However, he states: "The makers of the revolution—Copernicus, Kepler, Galileo, Descartes, Newton, and many others—had to selectively appropriate relevant ideas, transform them, and create new auxiliary concepts in order to complete their task...

"[156] Critics note that lacking documentary evidence of transmission of specific scientific ideas, Bala's model will remain "a working hypothesis, not a conclusion".