Copper in biology

[13] Copper's essentiality was first discovered in 1928, when it was demonstrated that rats fed a copper-deficient milk diet were unable to produce sufficient red blood cells.

Health-compromised children, including those who are premature, malnourished, have low birth weights, develop infections, and who experience rapid catch-up growth spurts, are at elevated risk for copper deficiencies.

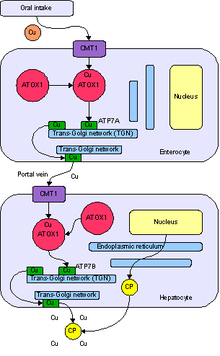

Copper is absorbed, transported, distributed, stored, and excreted in the body according to complex homeostatic processes which ensure a constant and sufficient supply of the micronutrient while simultaneously avoiding excess levels.

However, due to homeostatic regulation, the human body is capable of balancing a wide range of copper intakes for the needs of healthy individuals.

[17][18] Copper's essentiality is due to its ability to act as an electron donor or acceptor as its oxidation state fluxes between Cu1+(cuprous) and Cu2+ (cupric).

[19] As a component of about a dozen cuproenzymes, copper is involved in key redox (i.e., oxidation-reduction) reactions in essential metabolic processes such as mitochondrial respiration, synthesis of melanin, and cross-linking of collagen.

[19] A list of some key copper-containing enzymes and their functions is summarized below: The transport and metabolism of copper in living organisms is currently the subject of much active research.

[28] The site of maximal copper absorption is not known for humans, but is assumed to be the stomach and upper intestine because of the rapid appearance of 64Cu in the plasma after oral administration.

Extreme intakes of Vitamin C or iron can also affect copper absorption, reminding us of the fact that micronutrients need to be consumed as a balanced mixture.

[46] Excess copper (as well as other heavy metal ions like zinc or cadmium) may be bound by metallothionein and sequestered within intracellular vesicles of enterocytes (i.e., predominant cells in the small intestinal mucosa).

Copper released from intestinal cells moves to the serosal (i.e., thin membrane lining) capillaries where it binds to albumin, glutathione, and amino acids in the portal blood.

In North America, the U.S. Institute of Medicine (IOM) set the Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) for copper for healthy adult men and women at 0.9 mg/day.

There are conflicting reports on the extent of deficiency in the U.S. One review indicates approximately 25% of adolescents, adults, and people over 65, do not meet the Recommended Dietary Allowance for copper.

[70] Acquired copper deficiency has recently been implicated in adult-onset progressive myeloneuropathy[71] and in the development of severe blood disorders including myelodysplastic syndrome.

[64][78][79][19][20][75] Populations susceptible to copper deficiency include those with genetic defects for Menkes disease, low-birth-weight infants, infants fed cow's milk instead of breast milk or fortified formula, pregnant and lactating mothers, patients receiving total parenteral nutrition, individuals with "malabsorption syndrome" (impaired dietary absorption), diabetics, individuals with chronic diseases that result in low food intake, such as alcoholics, and persons with eating disorders.

On the other hand, Bo Lönnerdal commented that Gibson's study showed that vegetarian diets provided larger quantities of copper.

[38][80][81] Fetuses and infants of severely copper deficient women have increased risk of low birth weights, muscle weaknesses, and neurological problems.

Copper deficiencies in these populations may result in anemia, bone abnormalities, impaired growth, weight gain, frequent infections (colds, flu, pneumonia), poor motor coordination, and low energy.

Distinctions have emerged from studies that copper excess factors are different in normal populations versus those with increased susceptibility to adverse effects and those with rare genetic diseases.

In case reports of humans intentionally or accidentally ingesting high concentrations of copper salts (doses usually not known but reported to be 20–70 grams of copper), a progression of symptoms was observed including abdominal pain, headache, nausea, dizziness, vomiting and diarrhea, tachycardia, respiratory difficulty, hemolytic anemia, hematuria, massive gastrointestinal bleeding, liver and kidney failure, and death.

Episodes of acute gastrointestinal upset following single or repeated ingestion of drinking water containing elevated levels of copper (generally above 3–6 mg/L) are characterized by nausea, vomiting, and stomach irritation.

Reduced lysyl oxidase activity results in defective collagen and elastin polymerization and corresponding connective-tissue abnormalities including aortic aneurisms, loose skin, and fragile bones.

[citation needed] With early diagnosis and treatment consisting of daily injections of copper histidine intraperitoneally and intrathecally to the central nervous system, some of the severe neurological problems may be avoided and survival prolonged.

It has been suggested that heterozygote carriers of the Wilson's disease gene mutation may be potentially more susceptible to elevated copper intake than the general population.

[18] Further, a review of the data on single-allelic autosomal recessive diseases in humans does not suggest that heterozygote carriers are likely to be adversely affected by their altered genetic status.

This hypothesis was supported by the frequency of occurrence of parental consanguinity in most of these cases, which is absent in areas with elevated copper in drinking water and in which these syndromes do not occur.

[132] The copper complex of a synthetic salicylaldehyde pyrazole hydrazone (SPH) derivative induced human umbilical endothelial cell (HUVEC) apoptosis and showed anti-angiogenesis effect in vitro.

[140] The copper complex of salicylaldehyde benzoylhydrazone (SBH) derivatives showed increased efficacy of growth inhibition in several cancer cell lines, when compared with the metal-free SBHs.

[147] A copper intrauterine device (IUD) is a type of long-acting reversible contraception that is considered to be one of the most effective forms of birth control.

Swayback, a sheep disease associated with copper deficiency, imposes enormous costs on farmers worldwide, particularly in Europe, North America, and many tropical countries.