Corinth Canal

It is 6.4 kilometres (4 miles) in length and only 24.6 metres (80.7 feet) wide at sea level, making it impassable for many modern ships.

[7][8] Construction of a canal finally began under Roman Emperor Nero in 67 AD, using Jewish prisoners captured during the First Jewish–Roman War.

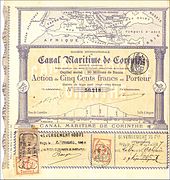

It was completed in 1893, but, due to the canal's narrowness, navigational problems, and periodic closures to repair landslides from its steep walls, it failed to attract the level of traffic expected by its operators.

The project was abandoned and Periander instead constructed a simpler and less costly overland portage road, named the Diolkos or stone carriageway, along which ships could be towed from one side of the isthmus to the other.

[13][14][15][7][16] Periander's change of heart is attributed variously to the great expense of the project, a lack of labour or a fear that a canal would have robbed Corinth of its dominant role as an entrepôt for goods.

[21] The emperor Nero was the first to attempt to construct the canal, personally breaking the ground with a pickaxe and removing the first basket-load of soil in 67 AD,[9] but the project was abandoned when he died shortly afterwards.

The Roman workforce, consisting of 6,000 Judean prisoners of war, started digging 40-to-50-metre-wide (130 to 160 ft) trenches from both sides, while a third group at the ridge drilled deep shafts for probing the quality of the rock (which were reused in 1881 for the same purpose).

A memorial of the attempt in the form of a relief of Hercules was left by Nero's workers and can still be seen in the canal cutting today.

[8] The Greek philosopher and Roman senator Herodes Atticus is known to have considered digging a canal in the 2nd century AD, but did not get a project under way.

[24] Construction resumed in 1890, when the project was transferred to a Greek company, and was completed on 25 July 1893 after eleven years' work.

Its high walls funnel wind along its length, and the different times of the tides in the two gulfs cause strong tidal currents in the channel.

By 1913, the total had risen to 1.5 million net tons, but the disruption caused by World War I resulted in a major decline in traffic.

[24] Another persistent problem was the heavily faulted nature of the sedimentary rock, in an active seismic zone, through which the canal is cut.

This required further expense in building retaining walls along the water's edge for more than half of the length of the canal, using 165,000 cubic metres of masonry.

The Germans surprised the defenders with a glider-borne assault in the early morning of 26 April and captured the bridge, but the British set off the charges and destroyed the structure.