Counter-Enlightenment

Its thinkers did not necessarily agree to a set of counter-doctrines but instead each challenged specific elements of Enlightenment thinking, such as the belief in progress, the rationality of all humans, liberal democracy, and the increasing secularisation of European society.

[1] Decades later, Joseph de Maistre in Sardinia and Edmund Burke in Britain both criticised the anti-religious ideas of the Enlightenment for leading to the Reign of Terror and a totalitarian police state following the French Revolution.

In the late 20th century, the concept of the Counter-Enlightenment was popularised by pro-Enlightenment historian Isaiah Berlin[2] as a tradition of relativist, anti-rationalist, vitalist, and organic thinkers stemming largely from Hamann and subsequent German Romantics.

[3] While Berlin is largely credited with having refined and promoted the concept, the first known use of the term in English occurred in 1949 and there were several earlier uses of it across other European languages,[4] including by German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche.

Despite criticism of the Enlightenment being a widely discussed topic in twentieth- and twenty-first century thought, the term "Counter-Enlightenment" was slow to enter general usage.

This German reaction to the imperialistic universalism of the French Enlightenment and Revolution, which had been forced on them first by the francophile Frederick II of Prussia, then by the armies of Revolutionary France and finally by Napoleon, was crucial to the shift of consciousness that occurred in Europe at this time, leading eventually to Romanticism.

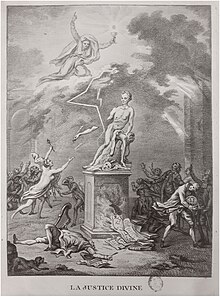

In his book Enemies of the Enlightenment (2001), historian Darrin McMahon extends the Counter-Enlightenment back to pre-Revolutionary France and down to the level of "Grub Street".

He delves into the obscure world of the "low Counter-Enlightenment" that attacked the encyclopédistes and fought to prevent the dissemination of Enlightenment ideas in the second half of the century.

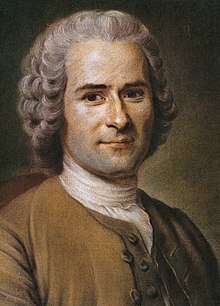

Cardiff University professor Graeme Garrard claims that historian William R. Everdell was the first to situate Rousseau as the "founder of the Counter-Enlightenment" in his 1971 dissertation and in his 1987 book, Christian Apologetics in France, 1730–1790: The Roots of Romantic Religion.

But similar to McMahon, Garrard traces the beginning of Counter-Enlightenment thought back to France and prior to the German Sturm und Drang movement of the 1770s.

The fact that the term "Enlightenment" was first used in 1894 in English to refer to a historical period supports the argument that it was a late construction projected back onto the 18th century.

Many leaders of the French Revolution and their supporters made Voltaire and Rousseau, as well as Marquis de Condorcet's ideas of reason, progress, anti-clericalism, and emancipation, central themes to their movement.

Many counter-revolutionary writers, such as Edmund Burke, Joseph de Maistre and Augustin Barruel, asserted an intrinsic link between the Enlightenment and the Revolution.

Many early Romantic writers such as Chateaubriand, Friedrich von Hardenberg (Novalis) and Samuel Taylor Coleridge inherited the Counter-Revolutionary antipathy towards the philosophes.

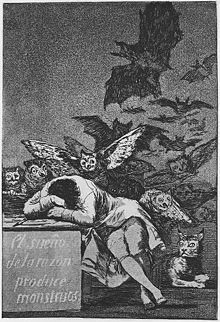

One particular concern to early Romantic writers was the allegedly anti-religious nature of the Enlightenment since the philosophes and Aufklärer were generally deists, opposed to revealed religion.

Some historians, such as Hamann, nevertheless contend that this view of the Enlightenment as an age hostile to religion is common ground between these Romantic writers and many of their conservative Counter-Revolutionary predecessors.

This view is expressed in Goya's Sleep of Reason, in which the nightmarish owl offers the dozing social critic of Los Caprichos a piece of drawing chalk.

[15][16] Prior to these historians, various philosophers described Fascism as a "revolt against reason" and a force hostile to scientific objectivity and rational inqury, namely Umberto Eco, Bertrand Russel, Richard Wolin and Jason Stanley.