Countercurrent exchange

For example, in a distillation column, the vapors bubble up through the downward flowing liquid while exchanging both heat and mass.

In cocurrent exchange the initial gradient is higher but falls off quickly, leading to wasted potential.

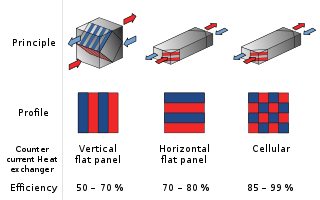

The result is that countercurrent exchange can achieve a greater amount of heat or mass transfer than parallel under otherwise similar conditions.

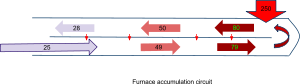

Countercurrent exchange when set up in a circuit or loop can be used for building up concentrations, heat, or other properties of flowing liquids.

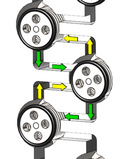

Specifically when set up in a loop with a buffering liquid between the incoming and outgoing fluid running in a circuit, and with active transport pumps on the outgoing fluid's tubes, the system is called a countercurrent multiplier, enabling a multiplied effect of many small pumps to gradually build up a large concentration in the buffer liquid.

Countercurrent exchange circuits or loops are found extensively in nature, specifically in biologic systems.

In vertebrates, they are called a rete mirabile, originally the name of an organ in fish gills for absorbing oxygen from the water.

Countercurrent exchange is a key concept in chemical engineering thermodynamics and manufacturing processes, for example in extracting sucrose from sugar beet roots.

Countercurrent multiplication is a similar but different concept where liquid moves in a loop followed by a long length of movement in opposite directions with an intermediate zone.

The incoming flow starting at a low concentration has a semipermeable membrane with water passing to the buffer liquid via osmosis at a small gradient.

The buffer liquid between the two tubes is at a gradually rising concentration, always a bit over the incoming fluid, in this example reaching 1200 mg/L.

In effect, this can be seen as a gradually multiplying effect—hence the name of the phenomena: a 'countercurrent multiplier' or the mechanism: Countercurrent multiplication, but in current engineering terms, countercurrent multiplication is any process where only slight pumping is needed, due to the constant small difference of concentration or heat along the process, gradually raising to its maximum.

There is no need for a buffer liquid, if the desired effect is receiving a high concentration at the output pipe.

The active transport pumps need only to overcome a constant and low gradient of concentration, because of the countercurrent multiplier mechanism.

The sequence of flow is as follows: Initially the countercurrent exchange mechanism and its properties were proposed in 1951 by professor Werner Kuhn and two of his former students who called the mechanism found in the loop of Henle in mammalian kidneys a Countercurrent multiplier[14] and confirmed by laboratory findings in 1958 by Professor Carl W.

[15] The theory was acknowledged a year later after a meticulous study showed that there is almost no osmotic difference between liquids on both sides of nephrons.

[16] Homer Smith, a considerable contemporary authority on renal physiology, opposed the model countercurrent concentration for 8 years, until conceding ground in 1959.

[20] When animals like the leatherback turtle and dolphins are in colder water to which they are not acclimatized, they use this CCHE mechanism to prevent heat loss from their flippers, tail flukes, and dorsal fins.

Such CCHE systems are made up of a complex network of peri-arterial venous plexuses, or venae comitantes, that run through the blubber from their minimally insulated limbs and thin streamlined protuberances.

It also enables the seabirds to remove the excess salt entering the body when eating, swimming or diving in the sea for food.

[22][23] The salt secreting gland has been found in seabirds like pelicans, petrels, albatrosses, gulls, and terns.

It has also been found in Namibian ostriches and other desert birds, where a buildup of salt concentration is due to dehydration and scarcity of drinking water.

Thus, all along the gland, there is only a small gradient to climb, in order to push the salt from the blood to the salty fluid with active transport powered by ATP.

The glands remove the salt efficiently and thus allow the birds to drink the salty water from their environment while they are hundreds of miles away from land.