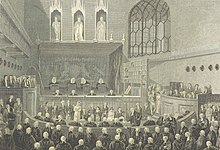

Court of King's Bench (England)

Created in the late 12th to early 13th century from the curia regis, the King's Bench initially followed the monarch on his travels.

To recover, the King's Bench undertook a scheme of revolutionary reform, creating less expensive, faster and more versatile types of pleading in the form of bills as opposed to the more traditional writs.

Although not immediately stemming the tide, it helped the King's Bench to recover and increase its workload in the long term.

The King's Bench's jurisdiction initially covered a wide range of criminal matters, any business not claimed by the other courts, and any cases concerning the monarch.

[3] In concert with the curia regis, eyre circuits staffed by itinerant judges dispensed justice throughout the country, operating on fixed paths at certain times.

For example, if the King left the country for an extended period of time (as Richard I, who spent the vast majority of his reign overseas did), the curia followed, making hearings difficult to hold.

[8]This was originally interpreted as the foundation of the King's Bench, with the Court of Common Pleas not coming into existence until the grant of Magna Carta.

Modern academics give 1234 as the founding date for the King's Bench as a fully independent tribunal, considering it part of the law reform which took place from 1232 to 1234.

This loss of business was quickly recognised by the King's Bench, which was urged by Fairfax J in 1501 to develop new remedies so that "subpoenas would not be used as often as they are at present".

From 1500 the King's Bench began reforming to increase its business and jurisdiction, with the tide finally turning in their favour by 1550.

[14] Eventually it became even more fictitious; if A wished to sue B merely for debt and detinue, a trespass writ would be obtained and then quietly dismissed when B was detained in custody.

In 1499 it enabled the enforcement of parol promises, which rendered Chancery subpoenas obsolete; later developments included the recovery of debts, suing for defamatory words (previously an ecclesiastical matter) and action on the case for trover and conversion.

[14] While the King's Bench was more revolutionary, the Common Pleas became increasingly conservative in its attempts to avoid ceding cases.

The disparity between the reformist King's Bench and conservative Common Pleas was exacerbated by the fact that the three Common Pleas prothonotaries could not agree on how to cut costs, leaving the court both expensive and of limited malleability while the King's Bench became faster, cheaper and more varied in its jurisdiction.

By 1558 the lawyers had succeeded in creating another method, enforced by the Court of King's Bench, through the action of assumpsit, which was technically for deceit.

[20] In Slade's Case, the Chief Justice of the King's Bench, John Popham, deliberately provoked the Common Pleas into bringing an assumpsit action to a higher court where the Justices of the King's Bench could vote, allowing them to overrule the Common Pleas and establish assumpsit as the main contractual action.

[23] In 1661 the Common Pleas attempted to reverse this by pushing for an Act of Parliament to abolish latitats based on legal fictions, forbidding "special bail" in any case where "the true cause of action" was not expressed in the process.

The Court of Common Pleas, however...never was able to obtain cognizance of – the peculiar subject of King's Bench jurisdiction – Crown Pleas... the Exchequer has adopted a similar course for, though it was originally confined to the trial of revenue cases, it has, by means of another fiction – the supposition that everybody sued is a debtor to the Crown, and further, that he cannot pay his debt, because the other party will not pay him, – opened its doors to every suitor, and so drawn to itself the right of trying cases, that were never intended to be placed within its jurisdiction.

Five reports were issued, from 25 March 1869 to 10 July 1874, with the first (dealing with the formation of a single Supreme Court of Judicature) considered the most influential.

[27] The report disposed of the previous idea of merging the common law and equity, and instead suggested a single Supreme Court capable of using both.

[33] The existence of the same courts as divisions of one unified body was a quirk of constitutional law, which prevented the compulsory demotion or retirement of Chief Justices.

[34] Due to a misunderstanding by Sir Edward Coke in his Institutes of the Lawes of England, academics thought for a long time that the King's Bench was primarily a criminal court.

This was factually incorrect; no indictment was tried by the King's Bench until January 1323, and no record of the court ordering the death penalty is found until halfway through Edward II's reign.

With the exception of revenue matters, which were handled by the Exchequer of Pleas, the King's Bench held exclusive jurisdiction over these cases.