Cranioplasty

The temporalis muscle is reflected, and all surrounding soft tissues are removed, thus completely exposing the cranial defect.

Cranioplasty can restore the normal shape of the skull and prevent other complications caused by a sunken scalp, such as the "syndrome of the trephined".

[1][6] The surgery restores regular cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and cerebral blood flow dynamics, along with normal intracranial pressure.

Sufficient time is required for the recovery of the incision from the previous operation, as well as to clear any infections (both systemic and cranial).

[1] Some findings showed that a greater infection rate is associated with early cranioplasty due to interruption of wound healing,[8] as well as an increased incidence of hydrocephalus.

[9] Contrarily, there is evidence of early cranioplasty limiting complications caused by "syndrome of the trephined", including changes in cerebral blood flow and abnormal cerebrospinal fluid hydrodynamics.

The cranioplasty material is placed on the defect and is fixed to the surrounding skull with standard titanium plate and screws.

Small holes may be drilled on the bone graft or the prosthesis to prevent the accumulation of fluid under the repaired defect.

It is less commonly used than autografts due to its brittle nature, high infection rate, and poor ability to integrate with the human cranium.

[4] Complications occurring after cranioplasty include bacterial infection, bone flap resorption, wound dehiscence, hematoma, seizures, hygroma, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leakage.

[4] Bone resorption is more likely to occur in this group of patients when their cranioplasty is carried out over 6 weeks after their previous operation.

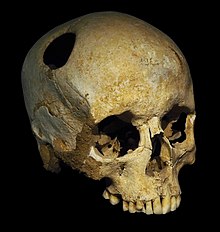

[2] In the Paracas region of present-day Peru, a skull from 2000 BC with a thin plate of gold covering a cranial defect was found.

[2] Moreover, defective skulls were found covered with coconut shells or palm leaves in ancient tribes of the Polynesian Islands.

[2] The earliest modern description of cranioplasty was written by surgeon Ibrahim bin Abdullah of the Ottoman Empire, in his surgical book Alâim-i Cerrâhîn in 1505.

[16] The first true description of cranioplasty in Europe was made by Fallopius in the 16th century, stating that the fractured cranium should be removed and be reinserted with a gold plate if the dura was damaged.

The operation was successful, but its use of canine bone was not accepted by the church and the man was forced to leave Russia.

[2][15] The prevalence of head injuries increased in the 20th century with the advancement of armaments, particularly the use of hand grenades in trench warfare during World War I.

[17] Along with a decreased mortality from suffering such injuries due to the development of cell debris removal, wound closing, and the use of antibiotics, cranioplasty techniques were therefore improved.

A successful case of reimplantation of cranial bone was reported by Sir William Macewen in 1885, popularising autografts to be material for cranioplasty.

[2] Cadaver skull was another type of allograft reported to be used as a cranioplasty material multiple times by Sicard and Dambrin from 1917 to 1919.

[2][3][10] The use of methyl methacrylate (PMMA) for cranioplasty has been developed since World War II, when there was a high demand for it to treat combat injuries, and used extensively since 1954.

[2][17][10][18] PMMA becomes malleable when an exothermic reaction occurs between its powder form and benzoyl peroxide, allowing it to be moulded to the cranial defect.

Disadvantages include its vulnerability to infection, as bacteria may adhere to its fibrous layer, as well as its brittle nature and absence of growth potential.

[10] Disadvantages of using titanium include its high cost, poor malleability, and disruption to CT scan images.