Creamware

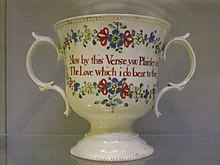

Creamware is a cream-coloured refined earthenware with a lead glaze over a pale body, known in France as faïence fine,[1] in the Netherlands as Engels porselein, and in Italy as terraglia inglese.

[2] Wedgwood and his English competitors sold creamware throughout Europe, sparking local industries, that largely replaced tin-glazed faience.

Originally lead powder or galena, mixed with a certain amount of ground calcined flint, was dusted on the ware, which was then given its one and only firing.

[13] Around 1740 a fluid glaze in which the ingredients were mixed and ground in water was invented, possibly by Enoch Booth of Tunstall, Staffordshire, according to one early historian, although this is disputed.

Several creamware types used moulds originally produced for the earlier salt-glazed stoneware goods, such as the typical plates illustrated opposite.

Combined with increasingly sophisticated decorative techniques, creamware quickly became established as the preferred ware for the dinner table amongst both middle and upper classes.

[20] Creamware during the 18th century was decorated in a variety of ways: The early process of using lead-powder produced a brilliant, transparent glaze of a rich cream colour.

Dry crystals of metallic oxides such as copper, iron and manganese were then dusted onto the ware to form patches of coloured decoration during firing.

The oily print was then transferred to the glazed earthenware surface which was then dusted with finely ground pigment in the chosen colour.

Excess powder was then removed and the ware was given a short firing in a muffle kiln to soften the glaze, burn off the oil and leave the printed image firmly bonded to the surface.

This method could be varied by transferring the oily print onto a 'glue-bat' – a slab of flexible gelatine that could be laid on the workbench whilst a globular pot was carefully rolled over it.

Transfer-printing was specialist and so generally outsourced in the early years: Sadler & Green of Liverpool were exclusive printers to Josiah Wedgwood by 1763, for example.

Attribution of pieces to particular factories has always been difficult because virtually no creamware was marked prior to Josiah Wedgwood's manufacture of it in Burslem.

Collectors, dealers and curators alike were frustrated in their efforts to ascribe pots to individual factories: it is frequently impossible to do so.

[29][30] Archaeological excavations of pottery sites in Staffordshire and elsewhere have helped provide some better-established typology to enable progress in attribution.