Credit card interest

As a result, optimal calculation of interest based on any information they have about the cardholder's credit risk is key to a card issuer's profitability.

A Brazilian bank-issued Visa or MasterCard to a new account holder can have annual interest as high as 240% even though inflation seems to have gone up per annum (Economist, May 2006).

Despite the "annual" in APR, it is not necessarily a direct reference for the interest rate paid on a stable balance over one year.

The bank calculates it by adding up the borrower's obligated minimum payments on loans, and dividing by the cardholder's income.

Banks vary widely in the proportion of credit card account income that comes from interest (depending upon their marketing mix).

In a typical UK card issuer, between 80% and 90% of cardholder generated income is derived from interest charges.

There is a legal obligation on U.S. issuers that the method of charging interest is disclosed and is sufficiently transparent to be fair.

This is typically done in the Schumer box, which lists rates and terms in writing to the cardholder applicant in a standard format.

If a lender uses that description, and charges interest in that way, then their disclosure is deemed to be sufficiently transparent and fair.

Today, in many cases because of strict laws, most card issuers do not charge any pre-payment penalties at all (except those that come naturally from the interest calculation method – see the section below).

The balance at the end of the billing cycle is multiplied by a factor in order to give the interest charge.

The reverse happens: the balance at the start of the previous billing cycle is multiplied by the interest factor in order to derive the charge.

The interest charged on the actual money borrowed over time can vary radically from month-to-month (rather than the APR remaining steady).

Despite the confusion of variable interest rates, the bank using this method does have a rationale; that is it costs the bank in strategic opportunity costs to vary the amount loaned from month-to-month, because they have to adjust assets to find the money to loan when it is suddenly borrowed, and find something to do with the money when it is paid back.

Although a detailed analysis can be done that shows that the effective interest can be slightly lower or higher each month than with the average daily balance method, depending upon the detailed calculation procedure used and the number of days in each month, the effect over the entire year provides only a trivial opportunity for arbitrage.

In general, differences between methods represent a degree of precision over charging the expected interest rate.

Precision is important because any detectable difference from the expected rate can theoretically be taken advantage of (through arbitrage) by cardholders (who have control over when to charge and when to pay), to the possible loss of profitability of the bank.

While cardholders can certainly affect their overall costs by managing their daily balances (for example, by buying or paying early or late in the month depending upon the calculation method), their opportunities for scaling this arbitrage to make large amounts of money are very limited.

(With no fee cardholders could create any daily balances advantageous to them through a series of cash advances and payments).

The rate took effect automatically if any of the listed conditions occur, which can include the following: one or two late payments, any amount overdue beyond the due date or one more cycle, any returned payment (such as an NSF check), any charging over the credit limit (sometimes including the bank's own fees), and – in some cases – any reduction of credit rating or default with another lender, at the discretion of the bank.

In effect, the cardholder is agreeing to pay the default rate on the balance owed unless all the listed events can be guaranteed not to happen.

A single late payment, or even a non-reconciled mistake on any account, could result in charges of hundreds or thousands of dollars over the life of the loan.

These high effective fees create a great incentive for cardholders to keep track of all their credit card and checking account balances (from which credit card payments are made) and for keeping wide margins (extra money or money available).

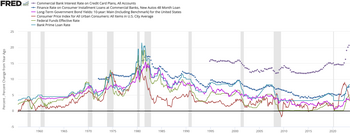

Many credit card issuers give a rate that is based upon an economic indicator published by a respected journal.

For example, most banks in the U.S. offer credit cards based upon the lowest U.S. prime rate as published in the Wall Street Journal on the previous business day to the start of the calendar month.

The bank, in effect, is marketing the convenience of the payment method (to receive fees and possible new lending income, when the cardholder does not pay), as well as the loans themselves.

[3] Additionally, the bank gets a chance to increase income by having more money lent out,[citation needed] and possibly an extra marketing transaction payment, either from the payee or sales side of the business, for contributing to the sale (in some cases as much as the entire interest payment, charged to the payee instead of the cardholder).

These combined "currencies" have accumulated to the point that they hold more value worldwide than U.S. (paper) dollars, and are the subject of company liquidation disputes and divorce settlements (Economist, 2005).

They are criticized for being highly inflationary, and subject to the whims of the card issuers (raising the prices after the points are earned).

Truth in Lending Act, because of the extra value offered by the bonus program, along with other terms, costs, and benefits created by other marketing gimmicks such as the ones cited in this article.