Cretoxyrhina

[a] It has been speculated that Cretoxyrhina hunted by lunging at its prey at high speeds to inflict powerful blows, similar to the great white shark today, and relied on strong eyesight to do so.

Cretoxyrhina was first described by the English paleontologist Gideon Mantell from eight C. mantelli teeth he collected from the Southerham Grey Pit near Lewes, East Sussex.

[11] In his 1822 bookThe fossils of the South Downs, co-written with his partner Mary Ann Mantell, he identified them as teeth pertaining to two species of locally-known modern sharks.

[12] In the third volume of his book Recherches sur les poissons fossiles, published in 1843, Swiss naturalist Louis Agassiz reexamined Mantell's eight teeth.

[18] In 1873, American paleontologist Joseph Leidy identified teeth from Kansas and Mississippi and described them under the species name Oxyrhina extenta.

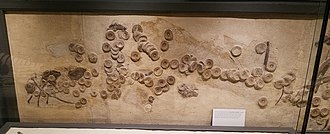

Charles H. Sternberg discovered the first skeleton in 1890, which he described in a 1907 paper:[17] The remarkable thing about this specimen is that the vertebral column, though of cartilaginous material, was almost complete, and that the large number of 250 teeth were in position.

[24] In 1968, a collector named Tim Basgall discovered another notable skeleton that, similar to FHSM VP-2187, also consisted of a near-complete vertebral column and a partially preserved skull.

[27][28] Originally, Glickman designated C. mantelli as the type species, but he abruptly replaced the position with another taxon identified as 'Isurus denticulatus' without explanation in a 1964 paper, a move now rejected as an invalid taxonomic amendment.

[d] Zhelezko also described a new species congeneric with C. mantelli based on tooth material from Kazakhstan, which he identified as Pseudoisurus vraconensis accordingly to his taxonomic reassessment.

[8][29] A 2013 study led by Western Australian Museum curator and paleontologist Mikael Siverson corrected the taxonomic error, reinstating the genus Cretoxyrhina and moving 'P'.

[e][10] Between 1997 and 2008, paleontologist Kenshu Shimada published a series of papers where he analyzed the skeletons of C. mantelli including those found by the Sternbergs using modernized techniques to extensively research the possible biology of Cretoxyrhina.

[10] Cretoxyrhina is a portmanteau of the word creto (short for Cretaceous) prefixed to the genus Oxyrhina, which is derived from the Ancient Greek ὀξύς (oxús, "sharp") and ῥίς (rhís, "nose").

[42] Tooth size of C. mantelli individuals inside the Western Interior Seaway peaked around 86 Ma during the latest Coniacian and then begins to slowly decline.

However, the Horseshoe Canyon Formation has only brackish water deposits despite Cretoxyrhina being a marine shark, making a likely possibility that the fossil was reworked from an older layer.

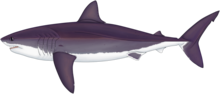

[9] Distinguishing characteristics of Cretoxyrhina teeth include a nearly symmetrical or slanted triangular shape, razor-like and non-serrated cutting edges, visible tooth necks (bourlette), and a thick enamel coating.

[34] A remeasurement conducted by Newbrey et al. (2013) found that C. mantelli and C. agassizensis reached sexual maturity at around four to five years of age and proposed a possible revision to the measurements of the growth rings in FHSM VP-2187.

A 2019 study led by Italian scientist Jacopo Amalfitano briefly measured the vertebrae from two C. mantelli fossils and found that the older individual died at around 26 years of age.

[11] Measurements were also conducted on other C. mantelli skeletons and a vertebra of C. agassizensis, yielding results of similar rates of rapid growth in early stages of life.

[10] Such rapid growth within mere years could have helped Cretoxyrhina better survive by quickly phasing out of infancy and its vulnerabilities, as a fully grown adult would have few natural predators.

[32][33] Cretoxyrhina's association with a diverse number of fossils showing signs of devourment confirms that it was an active apex predator that fed on much of the variety of marine megafauna in the Late Cretaceous.

[33] Most fossils of Cretoxyrhina feeding upon other animals consist of large and deep bite marks and punctures on bones, occasionally with teeth embedded in them.

[33] Cretoxyrhina may have occasionally fed on pterosaurs, evidenced by a set of cervical vertebrae of a Pteranodon from the Niobrara Formation with a C. mantelli tooth lodged deep between them.

If they were indeed a result of the former, that would mean that Cretoxyrhina most likely employed hunting strategies involving a main powerful and fatal blow similar to ram feeding seen in modern requiem sharks and lamnids.

As Cretoxyrhina possessed a robust stocky build capable of fast swimming, powerful kinetic jaws like the great white shark, and reaches lengths similar to or greater than it, a hunting style like this would be likely.

[71] The climate of marine ecosystems during the temporal range of Cretoxyrhina was generally much warmer than modern day due to higher atmospheric levels of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases influenced by the shape of the continents at the time.

[73] This interval also included a rise in global δ13C levels, which marks significant depletion of oxygen in the ocean, and caused the Cenomanian-Turonian anoxic event.

[75] The rest of the Cretaceous saw a progressive global cooling of Earth's oceans, leading to the appearance of temperate ecosystems and possible glaciation by the Early Maastrichtian.

[94] Large mosasaurs like Tylosaurus, which reached in excess of 14 meters (46 ft) in length,[44] may have competed with Cretoxyrhina, and evidence of interspecific interactions such as bite marks from either have been found.

[33] There were also many sharks that occupied a similar ecological role with Cretoxyrhina such as the cardabiodontids Cardabiodon[10] and Dwardius, the latter showing evidence of direct competition with C. vraconensis based on intricate distribution patterns between the two.

Their calculations found negative correlations between the distribution of Cretoxyrhina and the three potential competitors Squalicorax kaupi, Tylosaurus proriger, and Platecarpus spp.