Crime in Venezuela

[1][2][3][4] Rates of crime rapidly began to increase during the presidency of Hugo Chávez due to the institutional instability of his Bolivarian government, underfunding of police resources, and severe inequality.

[5] Chávez's government sought a cultural hegemony by promoting class conflict and social fragmentation, which in turn encouraged "criminal gangs to kill, kidnap, rob and extort".

[5] Following the "institutional crisis" surrounding the Venezuelan government and the socioeconomic issues shown during the Caracazo riots in 1989 and Hugo Chávez's 1992 coup attempts, homicides increased in Venezuela.

[5] This introduced to the Venezuelan population the notion of not following the societal rules and using violence to achieve goals, such as widespread looting during the Caracazo or by attempting to commit undemocratic coups such as in 1992.

[5] According to Gareth A. Jones and Dennis Rodgers in their book Youth violence in Latin America: Gangs and Juvenile Justice in Perspective, "With the change of political regime in 1999 and the initiation of the Bolivarian Revolution, a period of transformation and political conflict began, marked by a further increase in the number and rate of violent deaths" showing that in four years, the murder rate had increased from 25 per 100,000 in 1999 to 44 per 100,000 in 2003.

[27][28] Recently, the murder rate in Venezuela is the subject of some dispute according to the Associated Press, since Bolivarian government slowly denied access to homicide statistics.

[27] In 2010, The New York Times stated that according to news reports, data from human rights groups, such as the OVV's statistics, may actually be undercounting the number of those murdered in Venezuela.

[39] By 2018, Venezuela's murder rate–described as the highest in the world–had begun to decrease according to the OVV, with the organization stating that this downward trend was due to the millions of Venezuelans that emigrated from the country at the time.

[18] A more recent 2014 UNICEF report titled Hidden in Plain Sight, it was stated that in Venezuela, along with other Latin American countries, the leading cause of death for males between 10 and 19 is murder.

[46][47] He further explained that criminals felt that the Venezuelan government did not care for the problems of the higher classes, which in turn gave them a sense of impunity that created a large business of kidnapping.

[52][53] Available data underestimates the amount of express kidnapping, where victims are typically released in less than two days after relatives pay a quick ransom.

[51] According to Anthony Daquín, former adviser to the Minister of Interior and Justice of Venezuela, "[s]taff of the Directorate of Military Counterintelligence and SEBIN (Bolivarian National Intelligence Service) operate these bands kidnapping and extortion".

[56] In 2007, authorities in Colombia claimed that through laptops they had seized on a raid against Raul Reyes, they found documents purporting to show that Hugo Chávez offered payments of as much as $300 million USD to the FARC.

[59][60] According to Greg Palast, the claim about Chavez's $300 million is based on the following (translated) sentence: "With relation to the 300, which from now on we will call 'dossier', efforts are now going forward at the instructions of the cojo [slang term for 'cripple'], which I will explain in a separate note."

[64] In September 2013, an incident involving men from the Venezuelan National Guard placing 31 suitcases containing 1.3 tons of cocaine on a Paris flight astonished French authorities.

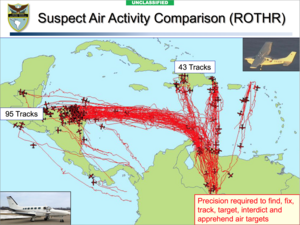

[79] Due to the largely unofficial economy that exists in Venezuela in which nearly every citizen participates, organized crime thrived as smuggling has been assisted by Colombian gangs, the Bolivarian National Guard and government officials.

Most kidnappings occur around "peace zones" where official police withdrew and gangs took over;[52] according to NBC News, "experts say the government has armed these groups ... [who] ... control large territories, financed through extortion and the drug trade".

[53] El País reported in 2014 that Chávez had years earlier assigned colectivos to be "the armed wing of the Bolivarian Revolution" for the Venezuelan government, giving them weapons, communication systems, motorcycles and surveillance equipment to exercise control in the hills of Caracas where police are forbidden entry.

[81] Despite the Venezuelan government's statements saying that only official authorities can carry weapons for the defense of Venezuela, colectivos are armed with automatic rifles such as AK-47s, submachine guns, fragmentation grenades, and tear gas.

[95] Some colectivos patrol the 23 de Enero barrio on motorcycles, masked and armed, supposedly to protect the neighborhood from criminals such as drug dealers.

[96] As blackouts continued, on 31 March, citizens protested the lack of electricity and water in Caracas and other cities; Maduro called again on the colectivos, asking them "to defend the peace of every barrio, of every block".

[109] As a result of the high levels of crime, Venezuelans were forced to change their ways of life due to the large insecurities they continuously experienced.

[110] 2014 Gallup polls showed that only 19% of Venezuelans felt safe walking alone at night, with nearly one quarter of the respondents stating that they or a household member had money stolen from them in the past year.

[1] While Venezuelans were suffering from shortages in Venezuela, the occasional looting of trucks full of goods became more common in the country with the robberies being committed by criminal gangs.

[13] In July 2015, BBC News stated that due to the common shortages in Venezuela, every week there are videos shared online showing Venezuelans looting supermarkets and trucks for food.

[112] In 2017, it was revealed that even military personnel became targets, with criminals instead beginning to just kill all of their victims before stealing their belongings, introducing a more violent face to theft in the country.

[123][124][125] Days after the replacement of the plan's creator Miguel Rodríguez Torres by Carmen Meléndez as Minister of the Popular Power for Interior, Justice and Peace,[126] In 2013, it was reported that Venezuela was one of the most weaponized areas in the world, with one firearm per two citizens.

[130][dead link] The majority of Venezuelans also believed that there was a poor due process of law while also thinking that the criminal justice system was not timely and judgement was ineffective.

They explained that "Weak security, deteriorating infrastructure, overcrowding, insufficient and poorly trained guards, and corruption allow armed gangs to effectively control prisons".

Jumping to the year 2014, the rate was 166, and as of 2016 the rate was at 173 [135] In 2018, Minister of Prison Service Iris Varela stated that when "[c]omparing the Venezuelan prison system with other penitentiary systems in the world, I can guarantee that this is the best in the world, because there have been no incidents", ignoring at least the April 2018 fire that occurred in the police station jails in Valencia, Carabobo where 68 people died per official figures.

* UN line between 2007 and 2012 is simulated missing data.

Source: CICPC [ 43 ] [ 44 ] [ 45 ]

* Express kidnappings may not be included in data