Croatisation

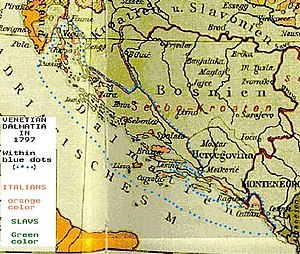

[8] However, after 1866, when the Veneto and Friuli regions were ceded by the Austrians to the newly formed Kingdom of Italy, Dalmatia remained part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, together with other Italian-speaking areas on the eastern Adriatic.

[9] During the meeting of the Council of Ministers of 12 November 1866, Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria outlined a wide-ranging project aimed at the Germanization or Slavization of the areas of the empire with an Italian presence:[10] His Majesty expressed the precise order that action be taken decisively against the influence of the Italian elements still present in some regions of the Crown and, appropriately occupying the posts of public, judicial, masters employees as well as with the influence of the press, work in South Tyrol, Dalmatia and Littoral for the Germanization and Slavization of these territories according to the circumstances, with energy and without any regard.

[14] Bartoli's evaluation was followed by other claims that Auguste de Marmont, the French Governor General of the Napoleonic Illyrian Provinces commissioned a census in 1809 which found that Dalmatian Italians comprised 29% of the total population of Dalmatia.

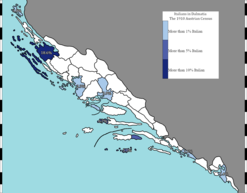

[19] In other Dalmatian localities, according to Austrian censuses, Italians experienced a sudden decrease: in the twenty years 1890-1910, in Rab they went from 225 to 151, in Vis from 352 to 92, in Pag from 787 to 23, completely disappearing in almost all the inland locations.

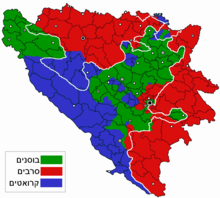

[30] During the 19th century, with the emergence of ideologies and active political engagements on introduction of ethno-national identity and nationhood among South Slavs, strong pressure was exerted on Bosnia and Herzegovina's diverse religious communities from outside forces, mainly from Serbia and Croatia.

Knežević's position and doctrine was that all Bosnians or Bosniaks are one people of three faiths, and that up to late 19th century, Croatian identity (and/or Serbian for that matter) never existed in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Ivan Franjo Jukić, who was his teacher and mentor earlier in his life and from whom he learned and adopted ideas, championed the notion that Catholics, Orthodox and Muslims are one nation and Bosnia and Herzegovina the country with deep cultural and historical roots.

[32] Dubravko Lovrenović, for instance, saw it as influencing a reception and interpretation of Bosnian medieval times, underlining its contemporary usage via revision and re-interpretation, in forms spanning from historical mythmaking by domestic and especially neighboring ethno-religious and nationalist elites, to identity and culture politics, often based on fringe science and public demagoguery of academic elite, with language and material heritage in its midst.

[40] The Croatian Defence Council (HVO), the military formation of Croats, took control of many municipal governments and services, removing or marginalising local Bosniak leaders.

The same statements and similar or related ones were also repeated in public speeches by single ministers, such as Mile Budak in Gospić and, a month later, by Mladen Lorković.