Cromwellian conquest of Ireland

Modern estimates suggest that during this period, Ireland experienced a demographic loss totalling around 15 to 20% of the pre-1641 population, due to fighting, famine and bubonic plague.

Cromwell landed near Dublin in August 1649 with an expeditionary force, and by the end of 1650 the Confederacy had been defeated, although sporadic guerrilla warfare continued until 1653.

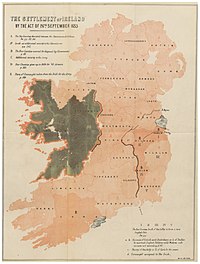

The Act for the Settlement of Ireland 1652 barred Catholics from most public offices and confiscated large amounts of their land, much of which was given to Protestant settlers.

These proved a continuing source of grievance, while the brutality of conquest means Cromwell remains a deeply reviled figure in Ireland.

[1] How far he was personally responsible for the atrocities is still debated; some writers have suggested his actions were within what were then viewed as accepted rules of war, while many academic historians disagree.

The first and most pressing reason was an alliance signed in 1649 between the Irish Confederate Catholics and Charles II, proclaimed King of Ireland in January 1649.

Many Parliamentarians wished to punish the Irish for alleged atrocities supposedly committed against the mainly Scottish Protestant settlers during the 1641 Uprising.

The Parliament had raised loans of £10 million under the Adventurers' Act to subdue Ireland since 1642, on the basis that its creditors would be repaid with land confiscated from Irish Catholic rebels.

A combined Royalist and Confederate force under the Marquess of Ormonde gathered at Rathmines, south of Dublin, to take the city and deprive the Parliamentarians of a port in which they could land.

[4] Oliver Cromwell called the battle "an astonishing mercy, so great and seasonable that we are like them that dreamed",[5] as it meant that he had a secure port at which he could land his army in Ireland, and that he retained the capital city.

With Admiral Robert Blake blockading the remaining Royalist fleet under Prince Rupert of the Rhine in Kinsale, Cromwell landed on 15 August with thirty-five ships filled with troops and equipment.

[10] The massacre of the garrison in Drogheda, including some after they had surrendered and some who had sheltered in a church, was received with horror in Ireland and is used today as an example of Cromwell's extreme cruelty.

They defeated the Scots at the Battle of Lisnagarvey (6 December 1649) and linked up with a Parliamentarian army composed of English settlers based around Derry in western Ulster, which was commanded by Charles Coote.

Cromwell was unable to take Waterford or Duncannon and the New Model Army had to retire to winter quarters, where many of its men died of disease, especially typhoid and dysentery.

The New Model Army met its only serious reverse in Ireland at the Siege of Clonmel, where its attacks on the town's defences were repulsed at a cost of up to 2,000 men.

However, in the case of Drogheda and Wexford no surrender agreement had been negotiated, and by the rules of continental siege warfare prevalent in the mid-17th century, this meant no quarter would be given; thus it can be argued that Cromwell's attitude had not changed.

From this point onwards, many Irish Catholics, including their bishops and clergy, questioned why they should accept Ormonde's leadership when his master, the King, had repudiated his alliance with them.

Coote's army, despite suffering heavy losses at the Siege of Charlemont, the last Catholic stronghold in the north, was now free to march south and invade the west coast of Ireland.

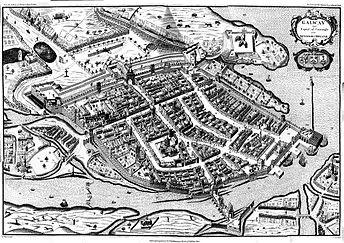

Ireton besieged Limerick while Charles Coote surrounded Galway, but they were unable to take the strongly fortified cities and instead blockaded them until a combination of hunger and disease forced them to surrender.

[14] The fall of Galway saw the end of organised resistance to the Cromwellian conquest, but fighting continued as small units of Irish troops launched guerrilla attacks on the Parliamentarians.

The guerrilla phase of the war had been going since late 1650 and at the end of 1651, despite the defeat of the main Irish or Royalist forces, there were still estimated to be 30,000 men in arms against the Parliamentarians.

Tories (from the Irish word tóraí meaning "pursuer" or "outlaw") operated from difficult terrain such as the Bog of Allen, the Wicklow Mountains and the drumlin country in the north midlands, and within months made the countryside extremely dangerous for all except large parties of Parliamentarian troops.

[18] In addition, some fifty thousand Irish people, including prisoners of war, were sold as indentured servants under the English Commonwealth regime.

The last Irish and Royalist forces (the remnants of the Confederate's Ulster Army, led by Philip O'Reilly) formally surrendered at Cloughoughter in County Cavan on 27 April 1653.

They cite such sources as Edmund Ludlow, the Parliamentarian commander in Ireland after Ireton's death, who wrote that the tactics used by Cromwell at Drogheda showed "extraordinary severity".

The main reason for this was the counter-guerrilla tactics used by such commanders as Henry Ireton, John Hewson and Edmund Ludlow against the Catholic population from 1650, when large areas of the country still resisted the Parliamentary Army.

[31] In addition, the whole post-war Cromwellian settlement of Ireland has been characterised by historians such as Mark Levene and Alan Axelrod as ethnic cleansing, in that it sought to remove Irish Catholics from the eastern part of the country.

[32] Colonial studies professor Katie Kane suggested that the invasion was comparable to the Native American genocide, drawing parallels between that event and the English treatment of Irish civilians.

A generation later, during the Glorious Revolution, many of the Irish Catholic landed class tried to reverse the remaining Cromwellian settlement in the Williamite War in Ireland (1689–91), where they fought en masse for the Jacobites.

As a result, Irish and English Catholics did not become full political citizens of the British state again until 1829 and were legally barred from buying valuable interests in land until the Papists Act 1778.