Cropping system

In evaluating whether a given crop will be planted, a farmer must consider its profitability, adaptability to changing conditions, resistance to disease, and requirement for specific technologies during growth or harvesting.

Crop rotation has been employed for thousands of years and has been widely found to increase yield and prevent harmful changes to the soil environment that limit productivity in the long term.

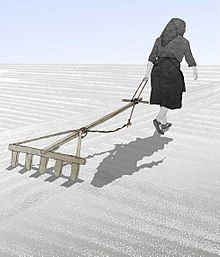

Different types of tillage result in varying amounts of crop residue being incorporated into the soil profile.

[11] In general, leaving residues on the soil surface results in a mulching effect which helps control erosion,[12] prevents excessive evaporation, and suppresses weeds,[13] but may necessitate the use of specialised planting equipment.

Under reduced or no-tillage, limited exposure to soil microorganisms can slow the rate of decomposition thus delaying the conversion of organic polymers to carbon dioxide and increasing the amount of carbon sequestered by the system,[16][17][18] although in poorly aerated soils this may be offset in part by an increase in nitrous oxide emissions.

This is a fast and cheap way to clear a field in preparation for the next planting, and can assist with pest control, but has a number of drawbacks: organic matter (carbon) is lost from the system, soil is exposed and becomes more susceptible to erosion, and the smoke produced is an atmospheric pollutant.

Nutrients are depleted during crop growth, and must be renewed or replaced in order for agriculture to continue on a piece of land.

[23] Therefore, there is considerable interest in developing nutrient management plans for individual plots which attempt to optimise fertiliser application rates.