Crow Terrace Poetry Trial

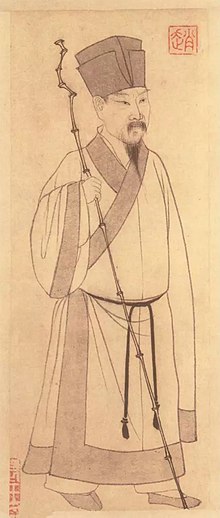

The most prominent of the dozens accused was the official, artist, and poet Su Shi (1037 – 1101), whose works of poetry were produced in court as evidence against him.

The Crow Terrace Poetry Trial had the significant effect of dampening subsequent creative expression and set a major negative precedent for freedom of speech, at least for the remainder of Song Dynasty China.

The Crow Terrace Poetry Trial took place in 1079, the 2nd year of the Yuanfeng era (Yuán Fēng 元豐; "Primary Abundance") 1078–1085 of the Song dynasty.

Su Shi was part of the politically opposed "conservative" group, later known as the "Yuanyou party", after the era-name during which they had exercised most power.

Wang Anshi's New Policies had their ups-and-downs in imperial favor, but initially he was able to sweep the political field of oppositional voices.

Su Shi's political vulnerability had been increased by a prior conviction, which resulted in his first sentence to exile, before the Crow Terrace incident.

His first exile was relatively mild: it was as governor of Hangzhou, on beautiful West Lake, where the poet Bai Juyi had previously governed, a city which would later become the capital of the Song dynasty after the fall of Kaifeng to invasion (much after Su Shi's lifetime).

[5] While Su Shi concentrated on making the lives of the local people in his charge better, and pursued his poetry which his position allowed time for, Wang Anshi's policies went awry.

What is certain is that Su Shi was exiled until emperor Shenzong became somewhat disillusioned with Wang Anshi (the powerful empress dowager had never been much of a fan of his).

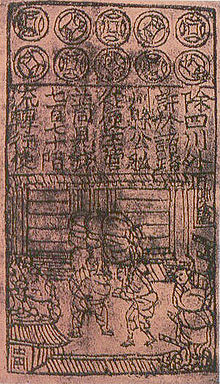

The Kaifeng merchants were becoming angry at the price inflation of wholesale goods together with additional tax increases and imposition of fees; and in north of the country a major drought followed by horrible famine occurred in 1074, displacing thousands of refugees.

However, this was just the warm-up to a bitter and deadly political struggle between the two factions in the ensuing years: now both groups had had their ranks decimated, and all sorts of charges of criminal impropriety were our would be filed.

However, despite recall and promotion, in the field of bitter factional politics, this made Su Shi a target for whatever charges could be invented or discovered.

[9] Another major figure indicted in this case was Wang Shen, a wealthy noble and imperial in-law, who was also a painter, poet, and friend of Su Shi.

The analysis as to the meanings and implications of Su Shi's writings was not clear-cut, in terms of whether they were actually treasonous, or whether they were in the bounds of acceptable expression.

Su Shi had in fact memorialized the emperor explicitly detailing his thoughts and feelings in this regard, in forceful prose.

[a] To avoid conviction, it was necessary for Su Shi to avoid the prosecution being able to prove that he had criticized or demeaned the emperor or his dynasty: using poetry to give indirect advice to the emperor which involved criticism of his subordinates and suggested policy improvements could be construed as a service to the state, and indeed there was a time-honored tradition of doing so, dating back through the earliest phases of the Chinese poetic tradition.

Whether Su Shi had crossed this line was also key in the case of the other persons accused, as their indictments centered around publishing or disseminating Su Shi's poems, which if illegally found to defame the emperor, automatically made them guilty of criminal conspiracy, if found that they were even merely aware of the poems and failed to report them to the authorities.

[7] and of "great irreverence toward the emperor":[7] conviction carried a mandatory death penalty by beheading, according to the statutory Song penal code, although this had never yet been applied.

Su Shi defended himself, denying accusations, or explaining how the lines of his poems really referred to the results of the actions of corrupt ministers, which according to ancient tradition it was incumbent as a duty of a loyal official to point out.

[12] According to Alfreda Murck, in a further confession, this time regarding the interpretation of a poem that he had written on the occasion of the banishment of Zeng Gong to serve in a remote government posting, Su Shi admitted: "This criticizes indirectly that many unfeeling men have recently been employed at Court, that their opinions are narrow-minded and make a raucous din like the sound of cicadas, and that they do not deserve to be heard.

The failure of the court to notice the extended meanings derivable by comparison of his rhymes with Du Fu's was apparent (to those in the know), and Su Shi and others, such as Wang Shen, having learned a way to avoid censorial persecution while still being able to express themselves to each other would continue to employ and expand upon this rhyme-matching, in conjunction with similarly coded painting.

Also, capital punishment by the public removal of Su Shi's head would have been a clear violation of the Song dynastic founder Taizu's precepts, who had had written in stone for all of his successors to read that "Officials and scholars must not be executed", as the 2nd of his 3 admonitions which each of his successors were supposed to kneel down before and to read as part of their ceremony of investiture as emperor.

[8] Some of his poetry began more and more to use such a deep and subtle allusive process that it would be difficult for those outside his group to grasp the real meaning, let alone put him back on trial.