Cryptanalysis

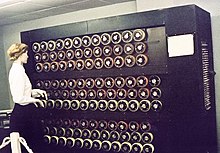

Even though the goal has been the same, the methods and techniques of cryptanalysis have changed drastically through the history of cryptography, adapting to increasing cryptographic complexity, ranging from the pen-and-paper methods of the past, through machines like the British Bombes and Colossus computers at Bletchley Park in World War II, to the mathematically advanced computerized schemes of the present.

Methods for breaking modern cryptosystems often involve solving carefully constructed problems in pure mathematics, the best-known being integer factorization.

To decrypt the ciphertext, the recipient requires a secret knowledge from the sender, usually a string of letters, numbers, or bits, called a cryptographic key.

As a basic starting point it is normally assumed that, for the purposes of analysis, the general algorithm is known; this is Shannon's Maxim "the enemy knows the system"[3] – in its turn, equivalent to Kerckhoffs's principle.

[4] This is a reasonable assumption in practice – throughout history, there are countless examples of secret algorithms falling into wider knowledge, variously through espionage, betrayal and reverse engineering.

In academic cryptography, a weakness or a break in a scheme is usually defined quite conservatively: it might require impractical amounts of time, memory, or known plaintexts.

Finally, an attack might only apply to a weakened version of cryptographic tools, like a reduced-round block cipher, as a step towards breaking the full system.

[citation needed] Although the actual word "cryptanalysis" is relatively recent (it was coined by William Friedman in 1920), methods for breaking codes and ciphers are much older.

[10] The first known recorded explanation of cryptanalysis was given by Al-Kindi (c. 801–873, also known as "Alkindus" in Europe), a 9th-century Arab polymath,[11][12] in Risalah fi Istikhraj al-Mu'amma (A Manuscript on Deciphering Cryptographic Messages).

[14] His breakthrough work was influenced by Al-Khalil (717–786), who wrote the Book of Cryptographic Messages, which contains the first use of permutations and combinations to list all possible Arabic words with and without vowels.

Frequency analysis of such a cipher is therefore relatively easy, provided that the ciphertext is long enough to give a reasonably representative count of the letters of the alphabet that it contains.

[16] Al-Kindi's invention of the frequency analysis technique for breaking monoalphabetic substitution ciphers[17][18] was the most significant cryptanalytic advance until World War II.

[15] In Europe, Italian scholar Giambattista della Porta (1535–1615) was the author of a seminal work on cryptanalysis, De Furtivis Literarum Notis.

[21] Successful cryptanalysis has undoubtedly influenced history; the ability to read the presumed-secret thoughts and plans of others can be a decisive advantage.

[23] During World War I, inventors in several countries developed rotor cipher machines such as Arthur Scherbius' Enigma, in an attempt to minimise the repetition that had been exploited to break the Vigenère system.

This change was particularly evident before and during World War II, where efforts to crack Axis ciphers required new levels of mathematical sophistication.

Even though computation was used to great effect in the cryptanalysis of the Lorenz cipher and other systems during World War II, it also made possible new methods of cryptography orders of magnitude more complex than ever before.

[citation needed] The historian David Kahn notes:[37] Many are the cryptosystems offered by the hundreds of commercial vendors today that cannot be broken by any known methods of cryptanalysis.

In 2010, former NSA technical director Brian Snow said that both academic and government cryptographers are "moving very slowly forward in a mature field.

While the effectiveness of cryptanalytic methods employed by intelligence agencies remains unknown, many serious attacks against both academic and practical cryptographic primitives have been published in the modern era of computer cryptography:[39] Thus, while the best modern ciphers may be far more resistant to cryptanalysis than the Enigma, cryptanalysis and the broader field of information security remain quite active.

[citation needed] Another distinguishing feature of asymmetric schemes is that, unlike attacks on symmetric cryptosystems, any cryptanalysis has the opportunity to make use of knowledge gained from the public key.

For example, Shor's Algorithm could factor large numbers in polynomial time, in effect breaking some commonly used forms of public-key encryption.