Crystal detector

[4] The most common type was the so-called cat's whisker detector, which consisted of a piece of crystalline mineral, usually galena (lead sulfide), with a fine wire touching its surface.

[17] It became obsolete with the development of vacuum tube receivers around 1920,[1][14] but continued to be used until World War II and remains a common educational project today thanks to its simple design.

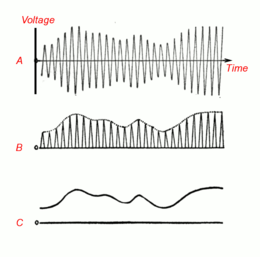

[18] As shown in the diagram on the right, A shows an amplitude modulated radio signal from the receiver's tuned circuit, which is applied as a voltage across the detector's contacts.

A bypass capacitor across the earphone terminals, in combination with the intrinsic forward resistance of the diode, creates a low-pass filter that smooths the waveform by removing the radio frequency carrier pulses and leaving the audio signal.

[6] An alternative method of adjustment was to use a battery-operated electromechanical buzzer connected to the radio's ground wire or inductively coupled to the tuning coil, to generate a test signal.

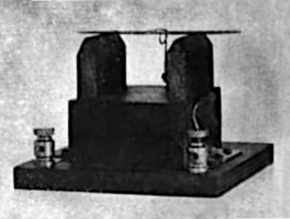

The detector consisted of two parts mounted next to each other on a flat nonconductive base: a crystalline mineral forming the semiconductor side of the junction, and a "cat whisker", a springy piece of thin metal wire, forming the metal side of the junction The most common crystal used was galena (lead sulfide, PbS), a widely occurring ore of lead.

[25][27][29] It was mounted on an adjustable arm with an insulated handle so that the entire exposed surface of the crystal could be probed from many directions to find the most sensitive spot.

[4] Precision detectors made for radiotelegraphy stations often used a metal needle instead of a "cat's whisker", mounted on a thumbscrew-operated leaf spring to adjust the pressure applied.

[33] Silicon carbide is a semiconductor with a wide band gap of 3 eV, so to make the detector more sensitive a forward bias voltage of several volts was usually applied across the junction by a battery and potentiometer.

The silicon detector was popular because it had much the same advantages as carborundum; its firm contact could not be jarred loose by vibration and it did not require a bias battery, so it saw wide use in commercial and military radiotelegraphy stations.

[4] Researchers investigating the effect of radio waves on various types of "imperfect" contacts to develop better coherers, invented crystal detectors.

His detectors consisted of a small galena crystal with a metal point contact pressed against it with a thumbscrew, mounted inside a closed waveguide ending in a horn antenna to collect the microwaves.

During the next four years, Pickard conducted an exhaustive search to find which substances formed the most sensitive detecting contacts, eventually testing thousands of minerals,[7] and discovered about 250 rectifying crystals.

[11] Long distance radio communication depended on high power transmitters (up to 1 MW), huge wire antennas, and a receiver with a sensitive detector.

[11][42] Using an oscilloscope made with Braun's new cathode ray tube, he produced the first pictures of the waveforms in a working detector, proving that it did rectify the radio wave.

It was found that, unlike the coherer, the rectifying action of the crystal detector allowed it to demodulate an AM radio signal, producing audio (sound).

The first person to exploit negative resistance practically was self-taught Russian physicist Oleg Losev, who devoted his career to the study of crystal detectors.

In 1922 working at the new Nizhny Novgorod Radio Laboratory he discovered negative resistance in biased zincite (zinc oxide) point contact junctions.

[64] While investigating crystal detectors in the mid-1920s at Nizhny Novgorod, Oleg Losev independently discovered that biased carborundum and zincite junctions emitted light.

[61][66] He theorized correctly that the explanation of the light emission was in the new science of quantum mechanics,[61] speculating that it was the inverse of the photoelectric effect discovered by Albert Einstein in 1905.

[63] In the 1920s, the amplifying triode vacuum tube, invented in 1907 by Lee De Forest, replaced earlier technology in both radio transmitters and receivers.

The amplifying vacuum tube radios which began to be mass-produced in 1921 had greater reception range, did not require the fussy adjustment of a cat whisker, and produced enough audio output power to drive loudspeakers, allowing the entire family to listen comfortably together, or dance to Jazz Age music.

The temperamental, unreliable action of the crystal detector had always been a barrier to its acceptance as a standard component in commercial radio equipment[1] and was one reason for its rapid replacement.

[54] After World War II, the development of modern semiconductor diodes finally made the galena cat whisker detector obsolete.

Nobel Laureate Walter Brattain, coinventor of the transistor, noted:[72] At that time you could get a chunk of silicon... put a cat whisker down on one spot, and it would be very active and rectify very well in one direction.

You moved it around a little bit-maybe a fraction, a thousandth of an inch-and you might find another active spot, but here it would rectify in the other direction.The "metallurgical purity" chemicals used by scientists to make synthetic experimental detector crystals had about 1% impurities which were responsible for such inconsistent results.

[72] During the 1930s progressively better refining methods were developed,[7] allowing scientists to create ultrapure semiconductor crystals into which they introduced precisely controlled amounts of trace elements (called doping).

[72] This for the first time created semiconductor junctions with reliable, repeatable characteristics, allowing scientists to test their theories, and later making manufacture of modern diodes possible.

The theory of rectification in a metal-semiconductor junction, the type used in a cat whisker detector, was developed in 1938 independently by Walter Schottky[73] at Siemens & Halske research laboratory in Germany and Nevill Mott[74] at Bristol University, UK.

[70] The development of microwave technology during the 1930s run up to World War II for use in military radar led to the resurrection of the point contact crystal detector.