Crystallographic restriction theorem

The crystallographic restriction theorem in its basic form was based on the observation that the rotational symmetries of a crystal are usually limited to 2-fold, 3-fold, 4-fold, and 6-fold.

However, quasicrystals can occur with other diffraction pattern symmetries, such as 5-fold; these were not discovered until 1982 by Dan Shechtman.

[1] Crystals are modeled as discrete lattices, generated by a list of independent finite translations (Coxeter 1989).

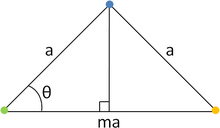

We now confine our attention to the plane in which the symmetry acts (Scherrer 1946), illustrated with lattice vectors in the figure.

So collect all the edge displacements to begin at a single lattice point.

The existence of quasicrystals and Penrose tilings shows that the assumption of a linear translation is necessary.

And without the discrete lattice assumption, the above construction not only fails to reach a contradiction, but produces a (non-discrete) counterexample.

Thus 5-fold rotational symmetry cannot be eliminated by an argument missing either of those assumptions.

A Penrose tiling of the whole (infinite) plane can only have exact 5-fold rotational symmetry (of the whole tiling) about a single point, however, whereas the 4-fold and 6-fold lattices have infinitely many centres of rotational symmetry.

Due to periodicity of the crystal, the new vector r' which connects them must be equal to an integer multiple of r: with

Examples Selecting a basis formed from vectors that spans the lattice, neither orthogonality nor unit length is guaranteed, only linear independence.

Similar as in other proofs, this implies that the only allowed rotational symmetries correspond to 1,2,3,4 or 6-fold invariance.

For example, wallpapers and crystals cannot be rotated by 45° and remain invariant, the only possible angles are: 360°, 180°, 120°, 90° or 60°.

When the dimension of the lattice rises to four or more, rotations need no longer be planar; the 2D proof is inadequate.

In this view, a 3D quasicrystal with 8-fold rotation symmetry might be described as the projection of a slab cut from a 4D lattice.

Projecting a slab of hypercubes along the first two dimensions of the new coordinates produces an Ammann–Beenker tiling (another such tiling is produced by projecting along the last two dimensions), which therefore also has 8-fold rotational symmetry on average.

To state the restriction for all dimensions, it is convenient to shift attention away from rotations alone and concentrate on the integer matrices (Bamberg, Cairns & Kilminster 2003).

We say that a matrix A has order k when its k-th power (but no lower), Ak, equals the identity.

Using the fundamental theorem of arithmetic, we can write any other positive integer uniquely as a product of prime powers, m = Πα pαk α; set ψ(m) = Σα ψ(pαk α).

Integer matrices are not limited to rotations; for example, a reflection is also a symmetry of order 2.

The crystallographic restriction theorem can be formulated in terms of isometries of Euclidean space.

The theorem also excludes S8, S12, D4d, and D6d (see point groups in three dimensions), even though they have 4- and 6-fold rotational symmetry only.

The result in the table above implies that for every discrete isometry group in four- and five-dimensional space which includes translations spanning the whole space, all isometries of finite order are of order 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 10, or 12.

Compatible : 6-fold (3-fold), 4-fold (2-fold)

Incompatible : 8-fold, 5-fold