Tessellation

A real physical tessellation is a tiling made of materials such as cemented ceramic squares or hexagons.

Such tilings may be decorative patterns, or may have functions such as providing durable and water-resistant pavement, floor, or wall coverings.

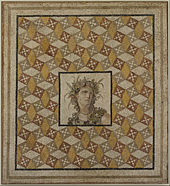

Historically, tessellations were used in Ancient Rome and in Islamic art such as in the Moroccan architecture and decorative geometric tiling of the Alhambra palace.

Tessellations form a class of patterns in nature, for example in the arrays of hexagonal cells found in honeycombs.

Tessellations were used by the Sumerians (about 4000 BC) in building wall decorations formed by patterns of clay tiles.

[1] Decorative mosaic tilings made of small squared blocks called tesserae were widely employed in classical antiquity,[2] sometimes displaying geometric patterns.

He wrote about regular and semiregular tessellations in his Harmonices Mundi; he was possibly the first to explore and to explain the hexagonal structures of honeycomb and snowflakes.

[5][6][7] Some two hundred years later in 1891, the Russian crystallographer Yevgraf Fyodorov proved that every periodic tiling of the plane features one of seventeen different groups of isometries.

Other prominent contributors include Alexei Vasilievich Shubnikov and Nikolai Belov in their book Colored Symmetry (1964),[10] and Heinrich Heesch and Otto Kienzle (1963).

[11] In Latin, tessella is a small cubical piece of clay, stone, or glass used to make mosaics.

It corresponds to the everyday term tiling, which refers to applications of tessellations, often made of glazed clay.

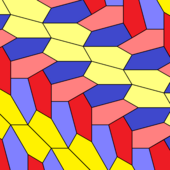

The artist M. C. Escher is famous for making tessellations with irregular interlocking tiles, shaped like animals and other natural objects.

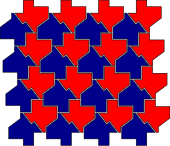

[16] If suitable contrasting colours are chosen for the tiles of differing shape, striking patterns are formed, and these can be used to decorate physical surfaces such as church floors.

[19] No general rule has been found for determining whether a given shape can tile the plane or not, which means there are many unsolved problems concerning tessellations.

[6] The Swiss geometer Ludwig Schläfli pioneered this by defining polyschemes, which mathematicians nowadays call polytopes.

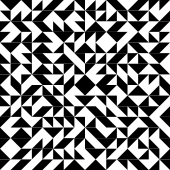

[30] Tilings with translational symmetry in two independent directions can be categorized by wallpaper groups, of which 17 exist.

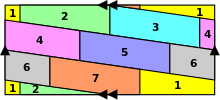

[38] A substitution rule, such as can be used to generate Penrose patterns using assemblies of tiles called rhombs, illustrates scaling symmetry.

Equivalently, we can construct a parallelogram subtended by a minimal set of translation vectors, starting from a rotational centre.

Certain polyhedra can be stacked in a regular crystal pattern to fill (or tile) three-dimensional space, including the cube (the only Platonic polyhedron to do so), the rhombic dodecahedron, the truncated octahedron, and triangular, quadrilateral, and hexagonal prisms, among others.

[58] Naturally occurring rhombic dodecahedra are found as crystals of andradite (a kind of garnet) and fluorite.

[69] Tessellations frequently appeared in the graphic art of M. C. Escher; he was inspired by the Moorish use of symmetry in places such as the Alhambra when he visited Spain in 1936.

[71][72] For his woodcut "Circle Limit IV" (1960), Escher prepared a pencil and ink study showing the required geometry.

[73] Escher explained that "No single component of all the series, which from infinitely far away rise like rockets perpendicularly from the limit and are at last lost in it, ever reaches the boundary line.

[77] Tessellation is used in manufacturing industry to reduce the wastage of material (yield losses) such as sheet metal when cutting out shapes for objects such as car doors or drink cans.

[78] Tessellation is apparent in the mudcrack-like cracking of thin films[79][80] – with a degree of self-organisation being observed using micro and nanotechnologies.

[82] In botany, the term "tessellate" describes a checkered pattern, for example on a flower petal, tree bark, or fruit.

The model, named after Edgar Gilbert, allows cracks to form starting from being randomly scattered over the plane; each crack propagates in two opposite directions along a line through the initiation point, its slope chosen at random, creating a tessellation of irregular convex polygons.

[89] Other natural patterns occur in foams; these are packed according to Plateau's laws, which require minimal surfaces.

In 1993, Denis Weaire and Robert Phelan proposed the Weaire–Phelan structure, which uses less surface area to separate cells of equal volume than Kelvin's foam.

[96][97] Inspired by Gardner's articles in Scientific American, the amateur mathematician Marjorie Rice found four new tessellations with pentagons.