Cubic zirconia

Although cubic, it was in the form of a polycrystalline ceramic: it was used as a refractory material, highly resistant to chemical and thermal attack (up to 2540 °C or 4604 °F).

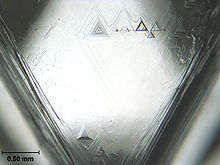

[3] In 1937, German mineralogists M. V. Stackelberg and K. Chudoba discovered naturally occurring cubic zirconia in the form of microscopic grains included in metamict zircon.

[4][5] As with the majority of grown diamond substitutes, the idea of producing single-crystal cubic zirconia arose in the minds of scientists seeking a new and versatile material for use in lasers and other optical applications.

Some of the earliest research into controlled single-crystal growth of cubic zirconia occurred in 1960s France, much work being done by Y. Roulin and R. Collongues.

Later, Soviet scientists under V. V. Osiko in the Laser Equipment Laboratory at the Lebedev Physical Institute in Moscow perfected the technique, which was then named skull crucible (an allusion either to the shape of the water-cooled container or to the form of crystals sometimes grown).

[7] In 1977, cubic zirconia began to be mass-produced in the jewelry marketplace by the Ceres Corporation, with crystals stabilized with 94% yttria.

This is largely due to the process allowing for temperatures of over 3000 °C to be achieved, lack of contact between crucible and material as well as the freedom to choose any gas atmosphere.

[3][12] The apparatus used in this process consists of a cup-shaped crucible surrounded by radio frequency-activated (RF-activated) copper coils and a water-cooling system.

The RF generator is switched on and the metallic chips quickly start heating up and readily oxidize into more zirconia.

The rate at which the crucible is removed from the RF coils is chosen as a function of the stability of crystallization dictated by the phase transition diagram.

If the concentration of Y2O3 is between 2.5-5% the resulting product will be PSZ (partially stabilized zirconia) while monophasic cubic crystals will form from around 8-40%.

Below 14% at low growth rates tend to be opaque indicating partial phase separation in the solid solution (likely due to diffusion in the crystals remaining in the high temperature region for a longer time).

Above this threshold crystals tend to remain clear at reasonable growth rates and maintains good annealing conditions.

The vast majority of YCZ (yttrium bearing cubic zirconia) crystals are clear with high optical perfection and with gradients of the refractive index lower than

Due to its optical properties yttrium cubic zirconia (YCZ) has been used for windows, lenses, prisms, filters and laser elements.

Coating finished cubic zirconia with a film of diamond-like carbon (DLC) is one such innovation, a process using chemical vapor deposition.

The coating is thought to quench the excess fire of cubic zirconia, while improving its refractive index, thus making it appear more like diamond.

Unlike diamond-like carbon and other hard synthetic ceramic coatings, the iridescent effect made with precious metal coatings is not durable, due to their extremely low hardness and poor abrasion wear properties, compared to the remarkably durable cubic zirconia substrate.

[15] The emergence of artificial stones such as cubic zirconia with optic properties similar to diamonds, could be an alternative for jewelry buyers given their lower price and noncontroversial history.

The Kimberley Process (KP) was established to deter the illicit trade of diamonds that fund civil wars in Angola and Sierra Leone.