Cunard Line

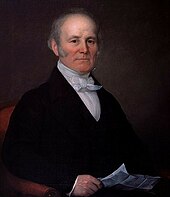

[2][3] In 1839, Samuel Cunard was awarded the first British transatlantic steamship mail contract, and the next year[4] formed the British and North American Royal Mail Steam-Packet Company in Glasgow with shipowner Sir George Burns together with Robert Napier, the famous Scottish steamship engine designer and builder, to operate the line's four pioneer paddle steamers on the Liverpool–Halifax–Boston route.

In response, the British Government provided Cunard with substantial loans and a subsidy to build two superliners needed to retain Britain's competitive position.

In 1818, the Black Ball Line opened a regularly scheduled New York–Liverpool service with clipper ships, beginning an era when American sailing packets dominated the North Atlantic saloon-passenger trade that lasted until the introduction of steamships.

[5] A Committee of Parliament decided in 1836 that to become more competitive, the mail packets operated by the Post Office should be replaced by private shipping companies.

[11] The famed Arctic explorer Admiral Sir William Edward Parry was appointed as Comptroller of Steam Machinery and Packet Service in April 1837.

[16] That November, Parry released a tender for North Atlantic monthly mail service to Halifax beginning in April 1839 using steamships with 300 horsepower.

[17] He also had the strong backing of Nova Scotian political leaders at the time when London needed to rebuild support in British North America after the rebellion.

[19] Napier and Cunard recruited other investors including businessmen James Donaldson, Sir George Burns, and David MacIver.

In May 1840, just before the first ship was ready, they formed the British and North American Royal Mail Steam Packet Company with initial capital of £270,000, later increased to £300,000 (£34,214,789 in 2023).

[17] (For more detail of the first investors in the Cunard Line and also the early life of Charles MacIver, see Liverpool Nautical Research Society's Second Merseyside Maritime History, pp.

At a time when the typical packet ship might take several weeks to cross the Atlantic, Britannia reached Halifax in 12 days and 10 hours, averaging 8.5 knots (15.7 km/h), before proceeding to Boston.

Two larger ships were quickly ordered, one to replace the Columbia, which sank at Seal Island, Nova Scotia, in 1843 without loss of life.

The American Government supplied Collins with a large annual subsidy to operate four wooden paddlers that were superior to Cunard's best,[21] as they demonstrated with three Blue Riband-winning voyages between 1850 and 1854.

Pacific sailed out of Liverpool just a few days before Persia was due to depart on her maiden voyage, and was never seen again; it was widely assumed at the time that the captain had pushed his ship to the limit to stay ahead of the new Cunarder, and had likely collided with an iceberg during what was a particularly severe winter in the North Atlantic.

[23] A few months later Persia inflicted a further blow to the Collins Line, regaining the Blue Riband with a Liverpool–New York voyage of 9 days 16 hours, averaging 13.11 knots (24.28 km/h).

While Collins' fortunes improved because of the lack of competition during the war, it collapsed in 1858 after its subsidy for carrying mail across the Atlantic was reduced by the US Congress.

[23] Cunard emerged as the leading carrier of saloon passengers and in 1862 commissioned Scotia, the last paddle steamer to win the Blue Riband.

Beginning with China, the line also replaced the last three wooden paddlers on the New York mail service with iron screw steamers that only carried saloon passengers.

Starting in 1887, Cunard's newly won leadership on the North Atlantic was threatened when Inman and then White Star responded with twin screw record-breakers.

[5] In 1897 Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse of Norddeutscher Lloyd raised the Blue Riband to 22.3 knots (41.3 km/h), and was followed by a succession of German record-breakers.

[26] Rather than match the new German speedsters, White Star – a rival which Cunard line would merge with – commissioned four very profitable Big Four ocean liners of more moderate speed for its secondary Liverpool–New York service.

[31] Due to First World War losses, Cunard began a post-war rebuilding programme including eleven intermediate liners.

David Kirkwood, MP for Clydebank where the unfinished Hull Number 534 had been sitting idle for two and a half years, made a passionate plea in the House of Commons for funding to finish the ship and restart the dormant British economy.

In 1936 the ex-White Star Majestic was sold when Hull Number 534, now named Queen Mary, replaced her in the express mail service.

[5] Cunard was in an especially good position to take advantage of the increase in North Atlantic travel during the 1950s and the Queens were a major generator of US currency for Great Britain.

[43] In June 1961, Cunard Eagle became the first independent airline in the UK to be awarded a licence by the newly constituted Air Transport Licensing Board (ATLB)[44][45] to operate a scheduled service on the prime Heathrow – New York JFK route, but the licence was revoked in November 1961 after main competitor, state-owned BOAC, appealed to Aviation Minister Peter Thorneycroft.

[51][56] BOAC countered Eagle's move to establish itself as a full-fledged scheduled transatlantic competitor on its Heathrow–JFK flagship route by forming BOAC-Cunard as a new £30 million joint venture with Cunard.

Coincidently, it was the same percentage that Cunard owned in Cunard-White Star Line[74] and the company historian later stated the acquisition was in-part due to the success of James Cameron’s blockbuster 1997 film, Titanic.

The company has also created the White Star Academy, an in-house programme for preparing new crew members for the service standards expected on Cunard ships.

[83] After the merger was completed, Carnival moved Cunard's headquarters to the offices of Princess Cruises in Santa Clarita, California, so that administrative, financial and technology services could be combined.