Porphyria

Porphyria /pɔːrˈfɪriə/ is a group of disorders in which substances called porphyrins build up in the body, adversely affecting the skin or nervous system.

[1] The types that affect the nervous system are also known as acute porphyria, as symptoms are rapid in onset and short in duration.

The major symptom of an acute attack is abdominal pain, often accompanied by vomiting, hypertension (elevated blood pressure), and tachycardia (an abnormally rapid heart rate).

[4] The most severe episodes may involve neurological complications: typically motor neuropathy (severe dysfunction of the peripheral nerves that innervate muscle), which leads to muscle weakness and potentially to quadriplegia (paralysis of all four limbs) and central nervous system symptoms such as seizures and coma.

[citation needed] Given the many presentations and the relatively low occurrence of porphyria, patients may initially be suspected to have other, unrelated conditions.

[7] Elevation of aminolevulinic acid from lead-induced disruption of heme synthesis results in lead poisoning having symptoms similar to acute porphyria.

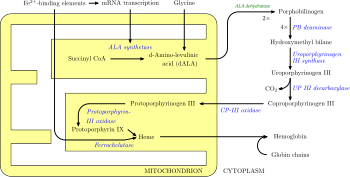

Such drugs include:[25][26][27] In humans, porphyrins are the main precursors of heme, an essential constituent of hemoglobin, myoglobin, catalase, peroxidase, and P450 liver cytochromes.

Hereditary coproporphyria, which is characterized by a deficiency in coproporphyrinogen oxidase, coded for by the CPOX gene, may also present with both acute neurologic attacks and cutaneous lesions.

[32] In nearly all cases of acute porphyria syndromes, urinary PBG is markedly elevated except for the very rare ALA dehydratase deficiency or in patients with symptoms due to hereditary tyrosinemia type I.

[citation needed] Further diagnostic tests of affected organs may be required, such as nerve conduction studies for neuropathy or an ultrasound of the liver.

[35] •Other Diagnosis[citation needed] Clinical Evaluation: A thorough medical history and physical examination focusing on symptoms related to photosensitivity, skin lesions, abdominal pain, and neurological manifestations.

A high-carbohydrate diet is typically recommended; in severe attacks, a dextrose 10% infusion is commenced, which may aid in recovery by suppressing heme synthesis, which in turn reduces the rate of porphyrin accumulation.

[citation needed] Any sign of low blood sodium (hyponatremia) or weakness should be treated with the addition of hematin, heme arginate, or even tin mesoporphyrin, as these are signs of impending syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone (SIADH) or peripheral nervous system involvement that may be localized or severe, progressing to bulbar paresis and respiratory paralysis.

[citation needed] It is recommended that patients with a history of acute porphyria, and even genetic carriers, wear an alert bracelet or other identification at all times.

Pain treatment with long-acting opioids, such as morphine, is often indicated, and, in cases where seizure or neuropathy is present, gabapentin is known to improve outcome.

Some benzodiazepines are safe and, when used in conjunction with newer anti-seizure medications such as gabapentin, offer a possible regimen for seizure control.

Other psychiatric symptoms such as anxiety, restlessness, insomnia, depression, mania, hallucinations, delusions, confusion, catatonia, and psychosis may occur.

[2] Patients with the acute porphyrias (AIP, HCP, VP) are at increased risk over their life for hepatocellular carcinoma (primary liver cancer) and may require monitoring.

The pain, burning, swelling, and itching that occur in erythropoietic porphyrias (EP) generally require avoidance of bright sunlight.

The signs may present from birth and include severe photosensitivity, brown teeth that fluoresce in ultraviolet light due to deposition of Type 1 porphyrins, and later hypertrichosis.

[49] In December 2014, afamelanotide received authorization from the European Commission as a treatment for the prevention of phototoxicity in adult patients with EPP.

It is inherited in an autosomal recessive manner, meaning both parents must carry a mutated gene for a child to develop the condition.

PCT can be sporadic or familial and is often associated with underlying liver disease, alcohol abuse, hepatitis C infection, or certain medications.

Additionally, advances in genetic testing and increased awareness of porphyria may lead to more accurate epidemiological data in the future.

In the early 1950s, patients with porphyrias (occasionally referred to as "porphyric hemophilia"[57]) and severe symptoms of depression or catatonia were treated with electroshock therapy.

Porphyria has been suggested as an explanation for the origin of vampire and werewolf legends, based upon certain perceived similarities between the condition and the folklore.

In 1985, biochemist David Dolphin's paper for the American Association for the Advancement of Science, 'Porphyria, Vampires, and Werewolves: The Aetiology of European Metamorphosis Legends', gained widespread media coverage, popularizing the idea.

[citation needed] The theory has been rejected by a few folklorists and researchers as not accurately describing the characteristics of the original werewolf and vampire legends nor the disease and as potentially stigmatizing people with porphyria.

In addition, the folkloric vampire, when unearthed, was always described as looking quite healthy ("as they were in life"), whereas owing to disfiguring aspects of the disease sufferers would not have passed the exhumation test.

The enzyme (hematin) necessary to alleviate symptoms is not absorbed intact on oral ingestion, and drinking blood would have no beneficial effect on the sufferer.