Cyanobacteria

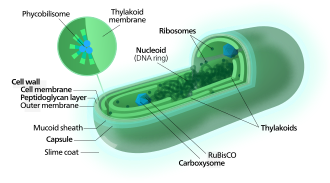

As of 2014[update] the taxonomy was under revision[3][4] Cyanobacteria (/saɪˌænoʊbækˈtɪəri.ə/) are a group of autotrophic gram-negative bacteria[7] of the phylum Cyanobacteriota that can obtain biological energy via oxygenic photosynthesis.

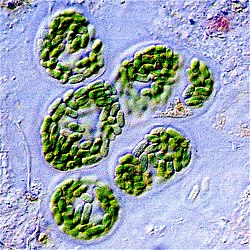

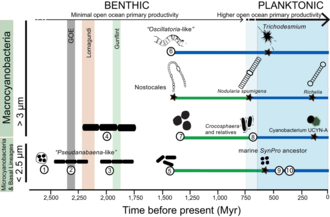

[note 1] Cyanobacteria are probably the most numerous taxon to have ever existed on Earth and the first organisms known to have produced oxygen,[13] having appeared in the middle Archean eon and apparently originated in a freshwater or terrestrial environment.

[27] Some species are nitrogen-fixing and live in a wide variety of moist soils and water, either freely or in a symbiotic relationship with plants or lichen-forming fungi (as in the lichen genus Peltigera).

[32][33] Some cyanobacteria form harmful algal blooms causing the disruption of aquatic ecosystem services and intoxication of wildlife and humans by the production of powerful toxins (cyanotoxins) such as microcystins, saxitoxin, and cylindrospermopsin.

[39][40][41][42] From these lineages, nitrogen-fixing cyanobacteria are particularly important because they exert a control on primary productivity and the export of organic carbon to the deep ocean,[39] by converting nitrogen gas into ammonium, which is later used to make amino acids and proteins.

[41][42][43] While some planktonic cyanobacteria are unicellular and free living cells (e.g., Crocosphaera, Prochlorococcus, Synechococcus); others have established symbiotic relationships with haptophyte algae, such as coccolithophores.

Growth is also favoured at higher temperatures which enable Microcystis species to outcompete diatoms and green algae, and potentially allow development of toxins.

[99] Cyanobacteria can interfere with water treatment in various ways, primarily by plugging filters (often large beds of sand and similar media) and by producing cyanotoxins, which have the potential to cause serious illness if consumed.

They are the most genetically diverse; they occupy a broad range of habitats across all latitudes, widespread in freshwater, marine, and terrestrial ecosystems, and they are found in the most extreme niches such as hot springs, salt works, and hypersaline bays.

[116][106] The relationships between cyanobionts (cyanobacterial symbionts) and protistan hosts are particularly noteworthy, as some nitrogen-fixing cyanobacteria (diazotrophs) play an important role in primary production, especially in nitrogen-limited oligotrophic oceans.

[120][121][122] Cyanobacteria, mostly pico-sized Synechococcus and Prochlorococcus, are ubiquitously distributed and are the most abundant photosynthetic organisms on Earth, accounting for a quarter of all carbon fixed in marine ecosystems.

For instance, billions of years ago, communities of marine Paleoproterozoic cyanobacteria could have helped create the biosphere as we know it by burying carbon compounds and allowing the initial build-up of oxygen in the atmosphere.

[36] Extreme blooms can also deplete water of oxygen and reduce the penetration of sunlight and visibility, thereby compromising the feeding and mating behaviour of light-reliant species.

In 2021, Maeda et al. discovered that oxygen produced by cyanobacteria becomes trapped in the network of polysaccharides and cells, enabling the microorganisms to form buoyant blooms.

As with other kinds of bacteria,[138] certain components of the pili may allow cyanobacteria from the same species to recognise each other and make initial contacts, which are then stabilised by building a mass of extracellular polysaccharide.

[128] The bubble flotation mechanism identified by Maeda et al. joins a range of known strategies that enable cyanobacteria to control their buoyancy, such as using gas vesicles or accumulating carbohydrate ballasts.

Evidence supports the existence of controlled cellular demise in cyanobacteria, and various forms of cell death have been described as a response to biotic and abiotic stresses.

However, cell death research in cyanobacteria is a relatively young field and understanding of the underlying mechanisms and molecular machinery underpinning this fundamental process remains largely elusive.

and Spirulina subsalsa found in the hypersaline benthic mats of Guerrero Negro, Mexico migrate downwards into the lower layers during the day in order to escape the intense sunlight and then rise to the surface at dusk.

[26] Stromatolites are layered biochemical accretionary structures formed in shallow water by the trapping, binding, and cementation of sedimentary grains by biofilms (microbial mats) of microorganisms, especially cyanobacteria.

[199] Lynn Margulis brought this hypothesis back to attention more than 60 years later[200] but the idea did not become fully accepted until supplementary data started to accumulate.

[205] The description of another independent and more recent primary endosymbiosis event between a cyanobacterium and a separate eukaryote lineage (the rhizarian Paulinella chromatophora) also gives credibility to the endosymbiotic origin of the plastids.

[215][212] Multiple lines of geochemical evidence support the occurrence of intervals of profound global environmental change at the beginning and end of the Proterozoic (2,500–542 Mya).

For bacterial transformation to take place, the recipient bacteria must be in a state of competence, which may occur in nature as a response to conditions such as starvation, high cell density or exposure to DNA damaging agents.

[229] "Vampirovibrionales" Gloeobacterales "Thermosynechococcales" Synechococcales Pleurocapsales Spirulinales Chroococcales Oscillatoriales Nostocales "Saganbacteria" (WOR1) "Marinamargulisbacteria" "Riflemargulisbacteria" (GWF2_35_9) "Termititenacia" "Caenarcanales" "Obscuribacterales" "Vampirovibrionales" "Gastranaerophilales" UBA7694 ("Blackallbacteria") S15B-MN24 ("Sericytochromatia"; "Tanganyikabacteria") Gloeobacterales Thermostichales Pseudanabaenales Gloeoemargaritales Prochlorococcaceae {PCC-6307} "Acaryochloridales" "Limnotrichales" Prochlorotrichales Synechococcales "Phormidesmiales" "Nodosilineales" Oculatellales "Elainellales" "Leptolyngbyales" Cyanobacteriales Historically, bacteria were first classified as plants constituting the class Schizomycetes, which along with the Schizophyceae (blue-green algae/Cyanobacteria) formed the phylum Schizophyta,[236] then in the phylum Monera in the kingdom Protista by Haeckel in 1866, comprising Protogens, Protamaeba, Vampyrella, Protomonae, and Vibrio, but not Nostoc and other cyanobacteria, which were classified with algae,[237] later reclassified as the Prokaryotes by Chatton.

[243] The currently accepted taxonomy as of 2025 is based on the List of Prokaryotic names with Standing in Nomenclature (LPSN)[244] and National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI).

[262] Researchers from several space agencies argue that cyanobacteria could be used for producing goods for human consumption in future crewed outposts on Mars, by transforming materials available on this planet.

Several cases of human poisoning have been documented, but a lack of knowledge prevents an accurate assessment of the risks,[268][269][270][271] and research by Linda Lawton, FRSE at Robert Gordon University, Aberdeen and collaborators has 30 years of examining the phenomenon and methods of improving water safety.

[272] Recent studies suggest that significant exposure to high levels of cyanobacteria producing toxins such as BMAA can cause amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS).

[281] Increased thermal stratification of lakes and reservoirs enables buoyant cyanobacteria to float upwards and form dense surface blooms, which gives them better access to light and hence a selective advantage over nonbuoyant phytoplankton organisms.

• Non- heterocytous : (c) Arthrospira maxima ,

Leaf and root colonization by cyanobacteria

(2) On the root surface, cyanobacteria exhibit two types of colonization pattern; in the root hair , filaments of Anabaena and Nostoc species form loose colonies, and in the restricted zone on the root surface, specific Nostoc species form cyanobacterial colonies.

(3) Co-inoculation with 2,4-D and Nostoc spp. increases para-nodule formation and nitrogen fixation. A large number of Nostoc spp. isolates colonize the root endosphere and form para-nodules. [ 106 ]

(a) O. magnificus with numerous cyanobionts present in the upper and lower girdle lists (black arrowheads) of the cingulum termed the symbiotic chamber.

(b) O. steinii with numerous cyanobionts inhabiting the symbiotic chamber.

(c) Enlargement of the area in (b) showing two cyanobionts that are being divided by binary transverse fission (white arrows).