Cycloid

In geometry, a cycloid is the curve traced by a point on a circle as it rolls along a straight line without slipping.

It was in the left hand try-pot of the Pequod, with the soapstone diligently circling round me, that I was first indirectly struck by the remarkable fact, that in geometry all bodies gliding along the cycloid, my soapstone for example, will descend from any point in precisely the same time.

The cycloid has been called "The Helen of Geometers" as, like Helen of Troy, it caused frequent quarrels among 17th-century mathematicians, while Sarah Hart sees it named as such "because the properties of this curve are so beautiful".

Mathematical historian Paul Tannery speculated that such a simple curve must have been known to the ancients, citing similar work by Carpus of Antioch described by Iamblichus.

[5] Galileo Galilei's name was put forward at the end of the 19th century[6] and at least one author reports credit being given to Marin Mersenne.

[7] Beginning with the work of Moritz Cantor[8] and Siegmund Günther,[9] scholars now assign priority to French mathematician Charles de Bovelles[10][11][12] based on his description of the cycloid in his Introductio in geometriam, published in 1503.

[5] Galileo originated the term cycloid and was the first to make a serious study of the curve.

[15] Constructing the tangent of the cycloid dates to August 1638 when Mersenne received unique methods from Roberval, Pierre de Fermat and René Descartes.

Mersenne passed these results along to Galileo, who gave them to his students Torricelli and Viviani, who were able to produce a quadrature.

[15] In 1658, Blaise Pascal had given up mathematics for theology but, while suffering from a toothache, began considering several problems concerning the cycloid.

Eight days later he had completed his essay and, to publicize the results, proposed a contest.

Pascal proposed three questions relating to the center of gravity, area and volume of the cycloid, with the winner or winners to receive prizes of 20 and 40 Spanish doubloons.

[15] Fifteen years later, Christiaan Huygens had deployed the cycloidal pendulum to improve chronometers and had discovered that a particle would traverse a segment of an inverted cycloidal arch in the same amount of time, regardless of its starting point.

In 1686, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz used analytic geometry to describe the curve with a single equation.

In 1696, Johann Bernoulli posed the brachistochrone problem, the solution of which is a cycloid.

[15] The cycloid through the origin, generated by a circle of radius r rolling over the x-axis on the positive side (y ≥ 0), consists of the points (x, y), with

The Cartesian equation is obtained by solving the y-equation for t and substituting into the x-equation:

When y is viewed as a function of x, the cycloid is differentiable everywhere except at the cusps on the x-axis, with the derivative tending toward

as the height difference from the cycloid's vertex (the point with a horizontal tangent and

This demonstration uses the rolling-wheel definition of cycloid, as well as the instantaneous velocity vector of a moving point, tangent to its trajectory.

Another geometric way to calculate the length of the cycloid is to notice that when a wire describing an involute has been completely unwrapped from half an arch, it extends itself along two diameters, a length of 4r.

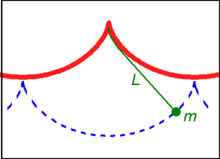

If a simple pendulum is suspended from the cusp of an inverted cycloid, such that the string is constrained to be tangent to one of its arches, and the pendulum's length L is equal to that of half the arc length of the cycloid (i.e., twice the diameter of the generating circle, L = 4r), the bob of the pendulum also traces a cycloid path.

Introducing a coordinate system centred in the position of the cusp, the equation of motion is given by:

is the angle that the straight part of the string makes with the vertical axis, and is given by

The 17th-century Dutch mathematician Christiaan Huygens discovered and proved these properties of the cycloid while searching for more accurate pendulum clock designs to be used in navigation.

If q is the product of that curvature with the circle's radius, signed positive for epi- and negative for hypo-, then the similitude ratio of curve to evolute is 1 + 2q.

The classic Spirograph toy traces out hypotrochoid and epitrochoid curves.

The cycloidal arch was used by architect Louis Kahn in his design for the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth, Texas.

It was also used by Wallace K. Harrison in the design of the Hopkins Center at Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire.

[20] Later work indicates that curtate cycloids do not serve as general models for these curves,[21] which vary considerably.