Spirograph

Spirograph is a geometric drawing device that produces mathematical roulette curves of the variety technically known as hypotrochoids and epitrochoids.

The well-known toy version was developed by British engineer Denys Fisher and first sold in 1965.

The Spirograph brand was relaunched worldwide in 2013, with its original product configurations, by Kahootz Toys.

In 1827, Greek-born English architect and engineer Peter Hubert Desvignes developed and advertised a "Speiragraph", a device to create elaborate spiral drawings.

A man named J. Jopling soon claimed to have previously invented similar methods.

[1] When working in Vienna between 1845 and 1848, Desvignes constructed a version of the machine that would help prevent banknote forgeries,[2] as any of the nearly endless variations of roulette patterns that it could produce were extremely difficult to reverse engineer.

The mathematician Bruno Abakanowicz invented a new Spirograph device between 1881 and 1900.

[3] Drawing toys based on gears have been around since at least 1908, when The Marvelous Wondergraph was advertised in the Sears catalog.

[4][5] An article describing how to make a Wondergraph drawing machine appeared in the Boys Mechanic publication in 1913.

[6] The definitive Spirograph toy was developed by the British engineer Denys Fisher between 1962 and 1964 by creating drawing machines with Meccano pieces.

Fisher exhibited his spirograph at the 1965 Nuremberg International Toy Fair.

US distribution rights were acquired by Kenner, Inc., which introduced it to the United States market in 1966 and promoted it as a creative children's toy.

Kenner later introduced Spirotot, Magnetic Spirograph, Spiroman, and various refill sets.

[7] In 2013 the Spirograph brand was re-launched worldwide, with the original gears and wheels, by Kahootz Toys.

[8] The original US-released Spirograph consisted of two differently sized plastic rings (or stators), with gear teeth on both the inside and outside of their circumferences.

Once either of these rings were held in place (either by pins, with an adhesive, or by hand) any of several provided gearwheels (or rotors)—each having holes for a ballpoint pen—could be spun around the ring to draw geometric shapes.

Later, the Super-Spirograph introduced additional shapes such as rings, triangles, and straight bars.

All edges of each piece have teeth to engage any other piece; smaller gears fit inside the larger rings, but they also can rotate along the rings' outside edge or even around each other.

Beginners often slip the gears, especially when using the holes near the edge of the larger wheels, resulting in broken or irregular lines.

Experienced users may learn to move several pieces in relation to each other (say, the triangle around the ring, with a circle "climbing" from the ring onto the triangle).

(in a real Spirograph, teeth on both circles prevent such slippage).

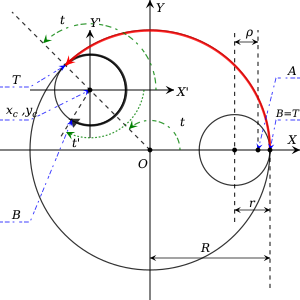

corresponds to the pen-hole in the inner disk of a real Spirograph.

Without loss of generality it can be assumed that at the initial moment the point

In order to find the trajectory created by a Spirograph, follow point

along their respective circles must be the same, therefore or equivalently, It is common to assume that a counterclockwise motion corresponds to a positive change of angle and a clockwise one to a negative change of angle.

, which (again in the absolute system) undergoes circular motion thus: As defined above,

as derived above to obtain equations describing the trajectory of point

It is convenient to represent the equation above in terms of the radius

It is now observed that and therefore the trajectory equations take the form Parameter

is a scaling parameter and does not affect the structure of the Spirograph.