Cypriot syllabary

The most obvious change is the disappearance of ideograms, which were frequent and represented a significant part of Linear A.

There is no evidence of a Semitic influence due to trade, but this pattern seemed to have evolved as the result of habitual use.

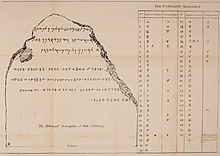

[3] Each sign generally stands for a syllable in the spoken language: e.g. ka, ke, ki, ko, ku.

[3] To see the glyphs above, you must have a compatible font installed, and your web browser must support Unicode characters in the U+10800–U+1083F range.

[2] Compare Linear B 𐀀𐀵𐀫𐀦 (a-to-ro-qo, reconstructed as *[án.tʰroː kʷos]) to Cypriot 𐠀𐠰𐠦𐠡𐠩 (a-to-ro-po-se, read right-to-left), both forms related to Attic Greek: ἄνθρωπος (ánthrōpos) "human".

[2] However, the syllabary can be subdivided into two different subtypes based on area: the "Common" and the South-Western or "Paphian".

Egyptologist Samuel Birch (1872), the numismatist Johannes Brandis (1873), the philologists Moritz Schmidt, Wilhelm Deecke, Justus Siegismund (1874) and the dialectologist H. L. Ahrens (1876) also contributed to decipherment.

The script found on these tablets has considerably evolved and the signs have become simple patterns of lines.

It details a contract made by the king Stasicyprus and the city of Idalium with the physician Onasilus and his brothers.

[4] As payment for the physicians' care for wounded warriors during a Persian siege of the city, the king promises them certain plots of land.

[4] Recent discoveries include a small vase dating back to the beginning of the 5th century BCE and a broken marble fragment in the Paphian (Paphos) script.

The vase is inscribed on two sides, providing two lists of personal names with Greek formations.

[4] Four inscribed objects were found in the British Museum stores, a silver cup from Kourion, a White Ware jug, and two limestone tablet fragments.

[2] The Cypriot syllabary was added to the Unicode Standard in April 2003 with the release of version 4.0.