DNA sequencing

Comparing healthy and mutated DNA sequences can diagnose different diseases including various cancers,[3] characterize antibody repertoire,[4] and can be used to guide patient treatment.

The DNA patterns in fingerprint, saliva, hair follicles, and other bodily fluids uniquely separate each living organism from another, making it an invaluable tool in the field of forensic science.

The advancements in DNA sequencing technology have made it possible to analyze and compare large amounts of genetic data quickly and accurately, allowing investigators to gather evidence and solve crimes more efficiently.

It has enabled scientists to identify genetic mutations and variations that are associated with certain diseases and disorders, allowing for more accurate diagnoses and targeted treatments.

Overall, the development of DNA sequencing technology has revolutionized the field of forensic science and has far-reaching implications for our understanding of genetics, medicine, and conservation biology.

In 1953, James Watson and Francis Crick put forward their double-helix model of DNA, based on crystallized X-ray structures being studied by Rosalind Franklin.

This provided the first conclusive evidence that proteins were chemical entities with a specific molecular pattern rather than a random mixture of material suspended in fluid.

Sanger's success in sequencing insulin spurred on x-ray crystallographers, including Watson and Crick, who by now were trying to understand how DNA directed the formation of proteins within a cell.

The first method for determining DNA sequences involved a location-specific primer extension strategy established by Ray Wu, a geneticist, at Cornell University in 1970.

[34][35][36] Between 1970 and 1973, Wu, scientist Radha Padmanabhan and colleagues demonstrated that this method can be employed to determine any DNA sequence using synthetic location-specific primers.

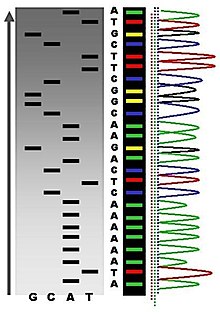

[52][8] A non-radioactive method for transferring the DNA molecules of sequencing reaction mixtures onto an immobilizing matrix during electrophoresis was developed by Herbert Pohl and co-workers in the early 1980s.

[56] This was followed by Applied Biosystems' marketing of the first fully automated sequencing machine, the ABI 370, in 1987 and by Dupont's Genesis 2000[57] which used a novel fluorescent labeling technique enabling all four dideoxynucleotides to be identified in a single lane.

By 1990, the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) had begun large-scale sequencing trials on Mycoplasma capricolum, Escherichia coli, Caenorhabditis elegans, and Saccharomyces cerevisiae at a cost of US$0.75 per base.

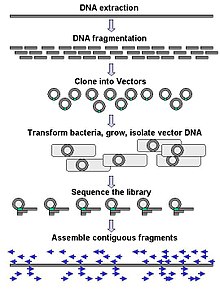

The circular chromosome contains 1,830,137 bases and its publication in the journal Science[59] marked the first published use of whole-genome shotgun sequencing, eliminating the need for initial mapping efforts.

NGS technology has tremendously empowered researchers to look for insights into health, anthropologists to investigate human origins, and is catalyzing the "Personalized Medicine" movement.

[67] On 1 April 1997, Pascal Mayer and Laurent Farinelli submitted patents to the World Intellectual Property Organization describing DNA colony sequencing.

Early industrial research into this method was based on a technique called 'exonuclease sequencing', where the readout of electrical signals occurred as nucleotides passed by alpha(α)-hemolysin pores covalently bound with cyclodextrin.

[115] In contrast, solid-state nanopore sequencing utilizes synthetic materials such as silicon nitride and aluminum oxide and it is preferred for its superior mechanical ability and thermal and chemical stability.

However, the essential properties of the MPSS output were typical of later high-throughput data types, including hundreds of thousands of short DNA sequences.

[90] Solexa, now part of Illumina, was founded by Shankar Balasubramanian and David Klenerman in 1998, and developed a sequencing method based on reversible dye-terminators technology, and engineered polymerases.

In 2004, Solexa acquired the company Manteia Predictive Medicine in order to gain a massively parallel sequencing technology invented in 1997 by Pascal Mayer and Laurent Farinelli.

In addition, data are now generated as contiguous full-length reads in the standard FASTQ file format and can be used as-is in most short-read-based bioinformatics analysis pipelines.

[125][citation needed] The patterned array of positively charged spots is fabricated through photolithography and etching techniques followed by chemical modification to generate a sequencing flow cell.

Unbound nucleotides are washed away before laser excitation of the attached labels then emit fluorescence and signal is captured by cameras that is converted to a digital output for base calling.

The devices were created from polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) and used Forster resonance energy transfer, FRET assays to read the sequences of DNA encompassed in the droplets.

[140][141] Third generation technologies aim to increase throughput and decrease the time to result and cost by eliminating the need for excessive reagents and harnessing the processivity of DNA polymerase.

Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry, or MALDI-TOF MS, has specifically been investigated as an alternative method to gel electrophoresis for visualizing DNA fragments.

Specifically, this method covalently links proteins of interest to the mRNAs encoding them, then detects the mRNA pieces using reverse transcription PCRs.

[162] Assessing the quality and quantity of nucleic acids both after extraction and after library preparation identifies degraded, fragmented, and low-purity samples and yields high-quality sequencing data.

[181][182] In most of the United States, DNA that is "abandoned", such as that found on a licked stamp or envelope, coffee cup, cigarette, chewing gum, household trash, or hair that has fallen on a public sidewalk, may legally be collected and sequenced by anyone, including the police, private investigators, political opponents, or people involved in paternity disputes.