Resolution independence

[1] As early as 1978, the typesetting system TeX due to Donald Knuth introduced resolution independence into the world of computers.

On June 11, 2012, Apple introduced the 2012 MacBook Pro with a resolution of 2880×1800 or 5.2 megapixels – doubling the pixel density in both dimensions.

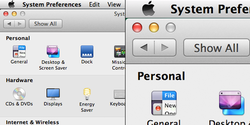

[3] The laptop shipped with a version of macOS that provided support to scale the user interface twice as big as it has previously been.

This feature is called HighDPI mode in macOS and it uses a fixed scaling factor of 2 to increase the size of the user interface for high-DPI screens.

Windows Vista also adds support for programs to declare themselves to the OS that they are high-DPI aware via a manifest file or using an API.

In addition, Windows 10 version 1703 brings back the XP-style GDI scaling under a "System (Enhanced)" option.

At runtime, the system transparently handles any scaling of the dp units, as necessary, based on the actual density of the screen in use.

The mechanism is also detected by desktop environments to set its own DPI, usually in conjunction with the EDID-based DisplayWidthMM family of Xlib functions.

[14] In 2013, the GNOME desktop environment began efforts to bring resolution independence ("hi-DPI" support) for various parts of the graphics stack.

Developer Alexander Larsson initially wrote[15] about changes required in GTK+, Cairo, Wayland and the GNOME themes.

[21] Although not related to true resolution independence, some other operating systems use GUIs that are able to adapt to changed font sizes.