TrueType

It has become the most common format for fonts on the classic Mac OS, macOS, and Microsoft Windows operating systems.

With widely varying rendering technologies in use today, pixel-level control is no longer certain in a TrueType font.

Apple also replaced some of their bitmap fonts used by the graphical user-interface of previous Macintosh System versions (including Geneva, Monaco and New York) with scalable TrueType outline-fonts.

The early TrueType systems — being still part of Apple's QuickDraw graphics subsystem — did not render Type 1 fonts on-screen as they do today.

When TrueType and the license to Microsoft was announced, John Warnock, co-founder and then CEO of Adobe, gave an impassioned speech in which he claimed Apple and Microsoft were selling snake oil, and then announced that the Type 1 format was open for anyone to use.

Although ATM initially cost money, rather than coming free with the operating system, it became a de facto standard for anyone involved in desktop publishing.

Anti-aliased rendering, combined with Adobe applications' ability to zoom in to read small type, and further combined with the now open PostScript Type 1 font format, provided the impetus for an explosion in font design and in desktop publishing of newspapers and magazines.

Second was Line Layout Manager, where particular sequences of characters can be coded to flip to different designs in certain circumstances, useful for example to offer ligatures for "fi", "ffi", "ct", etc.

Much of the technology in TrueType GX, including variations and substitution, lives on as AAT (Apple Advanced Typography) in macOS.

Subsequent advances in technology have introduced first anti-aliasing, which smooths the edges of fonts at the expense of a slight blurring, and more recently subpixel rendering (the Microsoft implementation goes by the name ClearType), which exploits the pixel structure of LCD based displays to increase the apparent resolution of text.

Microsoft has heavily marketed ClearType, and sub-pixel rendering techniques for text are now widely used on all platforms.

Microsoft also developed a "smart font" technology, named TrueType Open in 1994, later renamed to OpenType in 1996 when it merged support of the Adobe Type 1 glyph outlines.

Increasing resolutions and new approaches to screen rendering have reduced the requirement of extensive TrueType hinting.

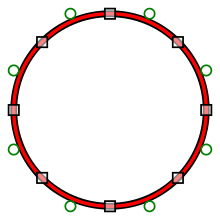

[6] The outlines of the characters (or glyphs) in TrueType fonts are made of straight line segments and quadratic Bézier curves.

These distort the control points which define the outline, with the intention that the rasterizer produce fewer undesirable features on the glyph.

Although incapable of receiving input and producing output as normally understood in programming, the TrueType instruction language does offer the other prerequisites of programming languages: conditional branching (IF statements), looping an arbitrary number of times (FOR- and WHILE-type statements), variables (although these are simply numbered slots in an area of memory reserved by the font), and encapsulation of code into functions.

The hallmark of effective TrueType glyph programming techniques is that it does as much as possible using variables defined just once in the whole font (e.g., stem widths, cap height, x-height).

Windows end user defined character editor (EUDCEDIT.EXE) creates TrueType font with name EUDC.TTE.