Dairy farming

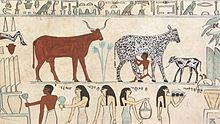

Dairy farming has a history that goes back to the early Neolithic era, around the seventh millennium BC, in many regions of Europe and Africa.

These cooling methods allowed dairy farms to preserve milk by reducing spoiling due to bacterial growth and humidity.

There has been substantial concern over the amount of waste output created by dairy industries, seen through manure disposal and air pollution caused by methane gas.

Centralized dairy farming as we understand it primarily developed around villages and cities, where residents were unable to have cows of their own due to a lack of grazing land.

In these systems the cow has a high degree of autonomy to choose her time of milking freely during the day (some alternatives may apply, depending on cow-traffic solution used at a farm level).

When windmills and well pumps were invented, one of their first uses on the farm, besides providing water for animals themselves, was for cooling milk, to extend its storage life, until it would be transported to the town market.

Tall, ten-gallon metal containers filled with freshly obtained milk, which is naturally warm, were placed in this cooling bath.

Ice eventually builds up around the coils, until it reaches a thickness of about three inches surrounding each pipe, and the cooling system shuts off.

Milk is extracted from the cow's udder by flexible rubber sheaths known as liners or inflations that are surrounded by a rigid air chamber.

The extracted milk passes through a strainer and plate heat exchangers before entering the tank, where it can be stored safely for a few days at approximately 40 °F (4 °C).

These philosophies as well as available technologies, local regulations, and environmental conditions manifest in different management of nutrition, housing, health, reproduction and waste.

Free stall barns and open lots are intensive housing options where feed is brought to the cattle at all times of year.

During this processes, called stripping the teat, the milking technician is looking for any discoloration or chunkiness that would indicate mastitis, an infection in the cow's mammary gland.

Many large dairies that deliver food to their cattle have a dedicated nutritionist who is responsible for formulating diets with animal health, milk production, and cost efficiency in mind.

Cattle are classified as ruminants (suborder ruminantia belonging to the order artiodactyl) as they are able to acquire nutrients from even low quality plant-based food, thanks mainly to their symbiotic relationship with the microbes that ferment it in a chamber of their stomachs called the rumen.

To keep cattle from selectively eating the most desirable parts of the diet, most produces feed a total mixed ration (TMR).

[17] Female calves born on a dairy farm will typically be raised as replacement stock to take the place of older cows that are no longer sufficiently productive.

Before a heifer can be bred she must reach sexual maturity and attain the proper body condition to successfully bear a calf.

Estrous cycles are the recurring hormonal and physiological changes that occur within the bodies of most mammalian females that lead to ovulation and the development of a suitable environment for embryonic and fetal growth.

The amount of milk produced per day during this period varies considerably by breed and by individual cow depending on her body condition, genetics, health, and nutrition.

Giving the cow a break during the final stages of pregnancy allows her mammary gland to regress and re-develop, her body condition to recover, and the calf to develop normally.

[10] There is also evidence that increased rates of mammary cell proliferation occur during the dry period that is essential to maintaining high production levels in subsequent lactation cycles.

Some of the larger dairies have planned 10 or more series of loafing barns and milking parlors in this arrangement, so that the total operation may include as many as 15,000 or 20,000 cows.

As a result, proposals to develop dairies of this size can be controversial and provoke substantial opposition from environmentalists including the Sierra Club and local activists.

The cycle of insemination, pregnancy, parturition, and lactation, followed by a "dry" period of about two months of forty-five to fifty days, before calving which allows udder tissue to regenerate.

[38] Milk replacer is generally a powder, which comes in large bags, and is added to precise amounts of water, and then fed to the calf via bucket, bottle or automated feeder.

[40] Milk replacer has climbed in cost US$15–20 a bag in recent years, so early weaning is economically crucial to effective calf management.

[45] Housing and management features common in modern dairy farms (such as concrete barn floors, limited access to pasture and suboptimal bed-stall design) have been identified as contributing risk factors to infections and injuries.

[citation needed] Advances in technology have mostly led to the radical redefinition of "family farms" in industrialized countries such as Australia, New Zealand, and the United States.

New questions have arisen concerning how the development of bigger farms places greater demands on strategies focused on financial control, leadership, and personnel issues.

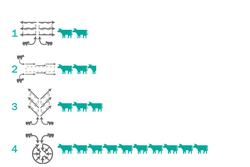

- Bali-Style 50 cows/h

- Swingover 60 cows/h

- Herringbone 75 cows/h

- Rotary 250 cows/h