14th Dalai Lama

His work includes focus on the environment, economics, women's rights, nonviolence, interfaith dialogue, physics, astronomy, Buddhism and science, cognitive neuroscience,[25][26] reproductive health and sexuality.

[29][30] Lhamo Thondup[31] was born on 6 July 1935 to a farming and horse trading family in the small hamlet of Taktser,[e] or Chija Tagtser,[36][f] at the edge of the traditional Tibetan region of Amdo in Qinghai Province.

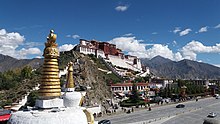

This vision was also interpreted to refer to a large monastery with a gilded roof and turquoise tiles, and a twisting path from there to a hill to the east, opposite which stood a small house with distinctive eaves.

[52] According to an interview with the 14th Dalai Lama, in the 1930s, Ma Bufang had seized this north-east corner of Amdo in the name of Chiang Kai-shek's weak government and incorporated it into the Chinese province of Qinghai.

[59][60] The 20,000-dollar fee for an escort was dropped, since the Muslim merchants invited them to join their caravan for protection; Ma Bufang sent 20 of his soldiers with them and was paid from both sides since the Chinese government granted him another 50,000 dollars for the expenses of the journey.

[87] In September 1954, he went to the Chinese capital to meet Chairman Mao Zedong with the 10th Panchen Lama and attend the first session of the National People's Congress as a delegate, primarily discussing China's constitution.

Stolen documents included a year's worth of the Dalai Lama's personal email, and classified government material relating to India, West Africa, the Russian Federation, the Middle East, and NATO.

[113] At the outset of the 1959 Tibetan uprising, fearing for his life, the Dalai Lama and his retinue fled Tibet with the help of the CIA's Special Activities Division,[115] crossing into India on 30 March 1959, reaching Tezpur in Assam on 18 April.

[142] When he travels abroad to give teachings there is usually a ticket fee calculated by the inviting organisation to cover the costs involved[142] and any surplus is normally to be donated to recognised charities.

[161][162] Dozens of videos of recorded webcasts of the Dalai Lama's public talks on general subjects for non-Buddhists like peace, happiness and compassion, modern ethics, the environment, economic and social issues, gender, the empowerment of women and so forth can be viewed in his office's archive.

In 1996 and 2002, he participated in the first two Gethsemani Encounters hosted by the Monastic Interreligious Dialogue at the Abbey of Our Lady of Getshemani, where Thomas Merton, whom the Dalai Lama had met in the late 1960s, had lived.

[169][170] In 2010, the Dalai Lama, joined by a panel of scholars, launched the Common Ground Project,[171] in Bloomington, Indiana (USA),[172] which was planned by himself and Prince Ghazi bin Muhammad of Jordan during several years of personal conversations.

[174] The Dalai Lama's lifelong interest in science[175][176] and technology[177] dates from his childhood in Lhasa, Tibet, when he was fascinated by mechanical objects like clocks, watches, telescopes, film projectors, clockwork soldiers[177] and motor cars,[178] and loved to repair, disassemble and reassemble them.

[179] On his first trip to the west in 1973 he asked to visit Cambridge University's astrophysics department in the UK and he sought out renowned scientists such as Sir Karl Popper, David Bohm and Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker,[178] who taught him the basics of science.

The Dalai Lama sees important common ground between science and Buddhism in having the same approach to challenge dogma on the basis of empirical evidence that comes from observation and analysis of phenomena.

[180] His growing wish to develop meaningful scientific dialogue to explore the Buddhism and science interface led to invitations for him to attend relevant conferences on his visits to the west, including the Alpbach Symposia on Consciousness in 1983 where he met and had discussions with the late Chilean neuroscientist Francisco J.

[178] Also in 1983, the American social entrepreneur and innovator R. Adam Engle,[181] who had become aware of the Dalai Lama's deep interest in science, was already considering the idea of facilitating for him a serious dialogue with a selection of appropriate scientists.

[183] Engle accepted, and Varela assisted him to assemble his team of six specialist scientists for the first 'Mind and Life' dialogue on the cognitive sciences,[184] which was eventually held with the Dalai Lama at his residence in Dharamsala in 1987.

[186] As Mind and Life Institute's remit expanded, Engle formalised the organisation as a non-profit foundation after the third dialogue, held in 1990, which initiated the undertaking of neurobiological research programmes in the United States under scientific conditions.

Treading a middle path in between these two lies the policy and means to achieve a genuine autonomy for all Tibetans living in the three traditional provinces of Tibet within the framework of the People's Republic of China.

This is called the Middle-Way Approach, a non-partisan and moderate position that safeguards the vital interests of all concerned parties-for Tibetans: the protection and preservation of their culture, religion and national identity; for the Chinese: the security and territorial integrity of the motherland; and for neighbours and other third parties: peaceful borders and international relations.

He does not believe that China implemented "true Marxist policy,"[250] and thinks the historical communist states such as the Soviet Union "were far more concerned with their narrow national interests than with the Workers' International".

[258][259] The Dalai Lama supports the anti-whaling position in the whaling controversy, but has criticised the activities of groups such as the Sea Shepherd Conservation Society (which carries out acts of what it calls aggressive nonviolence against property).

He emphasised "emotional disarmament" (seeing things with a clear and realistic perspective, without fear or rage) and wrote: "The outbreak of this terrible coronavirus has shown that what happens to one person can soon affect every other being.

While the journalists found "no independent evidence of direct Chinese financing," they reported that Beijing had "thrown its weight behind Shugden devotees" and the ISC became China's instrument to discredit the Dalai Lama.

"[317] In response to the controversy sparked by the interview, his office released a statement to clarify his remarks and put them into context, expressing that the Dalai Lama "is deeply sorry that people have been hurt by what he said and offers his sincere apologies."

The statement explains, the original context of the Dalai Lama's referring to the physical appearance of a female successor was a conversation with the then Paris editor of Vogue magazine, who had invited His Holiness in 1992 to guest-edit the next edition.

[319] The statement also noted, the Dalai Lama "consistently emphasizes the need for people to connect with each other on a deeper human level, rather than getting caught up in preconceptions based on superficial appearances.

[324] His office issued a statement saying that the Dalai Lama often teases "in an innocent and playful way," adding that he wants to apologise to those involved "for the hurt his words may have caused" and "regrets the incident".

[350][351] Following the resurfaced Lady Gaga incident, another video was posted on Spanish-language social media (notably X) showing him stroking a disabled girl's arm at an unknown event, drawing further criticism.